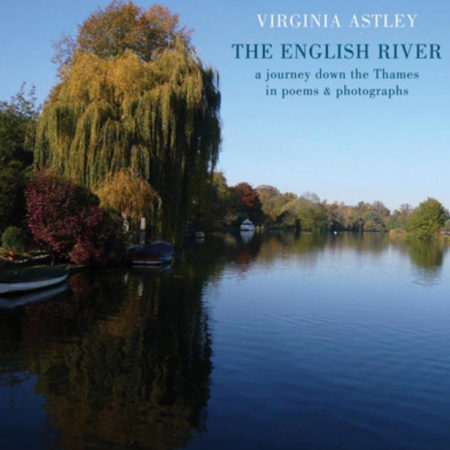

The English River: A Journey down the Thames in Poems & Photographs

Virginia Astley (2018)

Recommended by Bethan Roberts

I came to Astley, as most do, through her music. Her album Gardens Where We Feel Secure (1983) is a beautiful art of place in its own right, capturing an English summer day from dawn to dusk. Instrumentals interweave with field recordings of birds, sheep, churchbells, gardening, and rowing on the Thames, in and around Astley’s native Moulsford in Oxfordshire. Like Gardens, Astley’s The English River (her first full-length poetry collection) takes a soft and gentle approach. The book has the feel of a private notebook: the poems are tentative and sketch-like, offering glimpses of places which become increasingly bound up with the writer’s own memory (river poems seem to have the peculiar ability to facilitate this sort of reaching back and unlocking). In some ways the collection is the counterpart to the dazzling sinewy force and intellect of Alice Oswald’s Dart. The collection begins at the river’s source in Gloucestershire and in an elliptical meandering ends up downstream in the capital, with photographs and verse taking in flowers, birds, houses, weirs, locks and houses at various locations – including Moulsford – on its way. There are many arts of rivers, but what I like about this one is how personal and sort of artless it is: The English River evokes how a river flows through a person’s life and mind and what comes out the other side.

I came to Astley, as most do, through her music. Her album Gardens Where We Feel Secure (1983) is a beautiful art of place in its own right, capturing an English summer day from dawn to dusk. Instrumentals interweave with field recordings of birds, sheep, churchbells, gardening, and rowing on the Thames, in and around Astley’s native Moulsford in Oxfordshire. Like Gardens, Astley’s The English River (her first full-length poetry collection) takes a soft and gentle approach. The book has the feel of a private notebook: the poems are tentative and sketch-like, offering glimpses of places which become increasingly bound up with the writer’s own memory (river poems seem to have the peculiar ability to facilitate this sort of reaching back and unlocking). In some ways the collection is the counterpart to the dazzling sinewy force and intellect of Alice Oswald’s Dart. The collection begins at the river’s source in Gloucestershire and in an elliptical meandering ends up downstream in the capital, with photographs and verse taking in flowers, birds, houses, weirs, locks and houses at various locations – including Moulsford – on its way. There are many arts of rivers, but what I like about this one is how personal and sort of artless it is: The English River evokes how a river flows through a person’s life and mind and what comes out the other side.

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

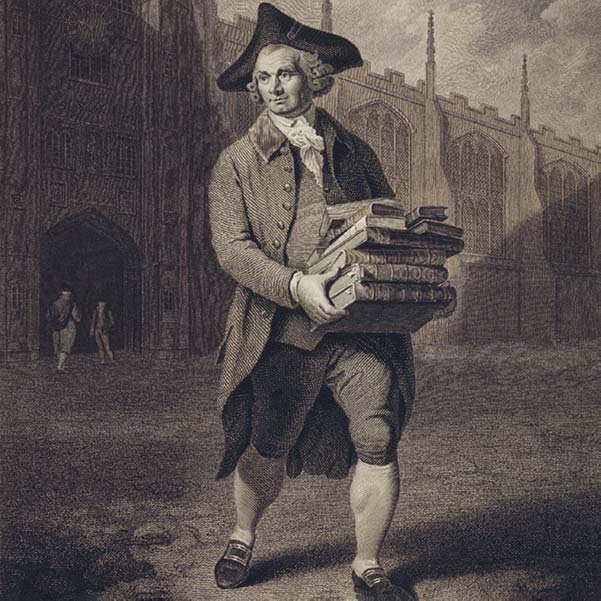

This is an edited collection, but nonetheless, the introduction sets out an extremely useful framework for thinking about books as ‘placed’ objects, and what happens to them when they begin to move and circulate. As Withers and Ogborn explain, while the history of the book is a discipline that has been long studied, far less attention has been paid to the geography of the book, a topic which is intimately connected to the cartographies of print production and distribution. The introduction is a great read if you are interested in gaining a critical vocabulary for talking about books as moving objects!

This is an edited collection, but nonetheless, the introduction sets out an extremely useful framework for thinking about books as ‘placed’ objects, and what happens to them when they begin to move and circulate. As Withers and Ogborn explain, while the history of the book is a discipline that has been long studied, far less attention has been paid to the geography of the book, a topic which is intimately connected to the cartographies of print production and distribution. The introduction is a great read if you are interested in gaining a critical vocabulary for talking about books as moving objects!

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by