by Dr. Mariana S. Mendes (Dresden Technical University)

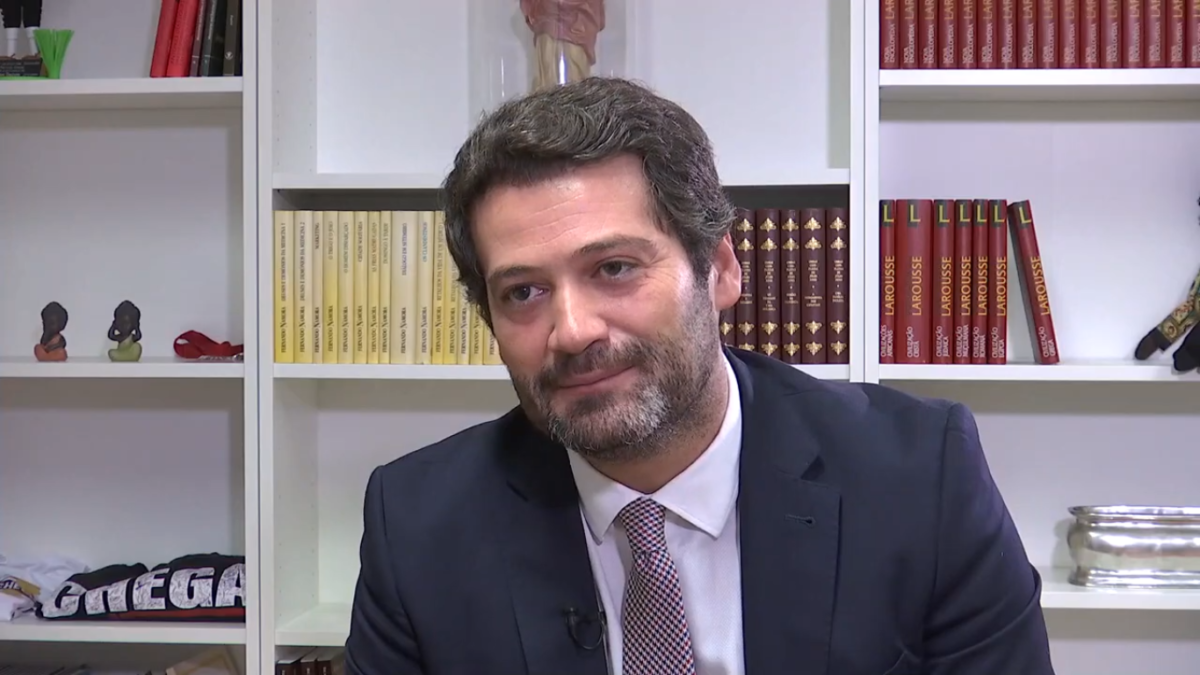

Europe’s burgeoning family of radical right parties has recently gained a new member in a country previously considered immune to such trends. The Portuguese party Chega (Enough) recently made headlines thanks to the result obtained by its leader in the country’s presidential election on January 24th 2021. With 12% of the popular vote, André Ventura – Chega’s leader and sole member of parliament – secured third place in the poll. Perhaps more importantly, he has also taken advantage of this contest to gain unprecedented personal visibility and establish Chega as a serious political competitor.

Introducing Chega

Officially founded in April 2019, Chega’s first electoral feat was the October 2019 legislative elections, where it gained 1,3% of the popular vote. It was one of three parties to gain parliamentary representation for the first time in 2019 (the other two being the liberal Iniciativa Liberal [1,3%] and the left-wing Livre [1,1%]). Of the three, Chega is by far the one which has benefited the most from parliamentary representation and the concomitant increase in media attention. In this respect, it has ostensibly profited from the tabloid-like style and rhetoric of its leader – which is prototypically right-wing populist, as it combines anti-establishment stances with the targeting of out-groups. This is a radical novelty in the Portuguese political scene.

Not only is André Ventura the party’s only public face – possessing a monopoly on party communications – but the party itself is held together, above all, by allegiance to him. Indeed, adherence to the leader is so strong that it has often been said that the party fosters a “cult of personality”. Though this is far from sufficient to prevent internal feuds (which have little to do with the leader, and more to do with intraparty power plays and personal antagonisms), there is one undisputable truth accepted within the party: Ventura is the uncontested leader and there is no Chega without him.

To start with, Chega is the creation of Ventura alone. Though he has obviously found supporters along the way, Chega was initiated by Ventura to put forward an agenda he had been unable to pursue previously as a member of the centre-right PSD (Partido Social Democrata), and grant him the political pre-eminence he had unsuccessfully tried to achieve there. His sense that there was fertile ground for a project like Chega dates back to the local elections in 2017 when, running as a PSD candidate in Loures, a municipality on Lisbon’s outskirts, he adopted a controversial platform explicitly targeting the Roma community for allegedly living on welfare benefits (among other things). His relatively good results, as well as the unprecedented media coverage his campaign received (unusual in local elections), were the first clear sign for him that the politicisation of “politically incorrect” topics could be a successful political strategy. Unable to disseminate his agenda within the PSD, and increasingly frustrated at the party’s internal hierarchy and centrist course, he quit in October 2018 and proceeded to create Chega, counting on the assistance of friends, acquaintances and crucially, social media (see Marchi, Riccardo, 2020).

Chega is not only the product of Ventura, but it seems to be above all a vehicle for Ventura. Kefford and McDonnell (2018) have noted perceptively that, while leaders are usually the expression of parties, so-called “personal parties” turn this formula on its head, with the parties instead being an expression of the leader. This seems to be the case with Chega so far, not only because Ventura created it and is the only face of the party, but also because its very existence, at least for the time being, depends entirely on him.

Nevertheless, it must be said that, on paper at least, Chega aims to be a party with an organisational structure and internal life similar to that of mainstream parties. In this regard, it has tried to appear a conventionally organised party – in contrast to, most flagrantly, the case of Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party in the Netherlands. Hence Chega has established party conferences, regional branches, a youth wing, and a (rapidly expanding) membership base (in January 2021, it was said to have 25,000 members already). If Chega’s organisational structure still appears underdeveloped, it is perhaps too early to tell whether this is the result of the party’s young age or an intended consequence of its “personal” nature.

“Growing pains”?

Tensions between establishing a properly functioning party and keeping it firmly under the leader’s control have emerged. While there are apparently internal democratic processes in place, Ventura has more than enough leverage to steer the party in directions he desires. This was most apparent at the party’s September 2020 convention, where Chega’s leader struggled to get his list of candidates to the party’s board approved (mostly because of conflicts among delegates). Refusing to give in, Ventura submitted the same list three times, threatening to resign if it was not approved at the third attempt… which in fact it was. Ventura’s grip on the party increased last December, when a directive was issued establishing sanctions against those who publicly criticise other party members or the party’s leadership, be it in the press or on social media. He justified this decision by saying he wanted to address a climate of internal strife that is allegedly damaging the reputation of the party – a climate often attributed to the party’s “growing pains”, in light of its rapidly expanding membership, lack of organisational capacity to absorb members, and the alleged infiltration of “opportunists”.

It is too soon to tell how such tensions will unfold. On the one hand, it is apparent that the party is keen to expand its grassroots presence, so as to maximise its electoral appeal. On the other hand, past research into personal parties has unequivocally shown that, as organisational entities, they tend to be “weak, shallow and opportunistic” (Gunther and Diamond, 2003). Ventura’s ideal model seems to be a party where power is concentrated at the top, but where the base is occasionally called on to directly elect the leader (which, to be fair, is not a model radically different from other parties in Portugal). This formula endows the leader with a legitimacy which allows him to justify sidestepping middle-ranking party members, as he did in the party’s September convention. Back then, and in a quintessentially populist fashion, Ventura claimed that power should remain with the grassroots (i.e. with their elected leader) and not with “behind-the-scene party structures”.

That said, Chega’s prospective problems have less to do with lack of internal democracy and more to do with internal conflict and an overreliance on Ventura. These are customary problems amongst populist and personal parties and it is easy to see why (the recent implosion of Thierry Baudet’s Forum for Democracy in the Netherlands being a case in point). Infighting, infiltration by extremists, scandals, or simple strategic miscalculations by leaders often turn these parties into their own worst enemies. And even if leaders are skillful political players, as seems to be the case with Ventura, the long-term viability of the project is critically dependent on the party’s ability to attract the electorate by not relying exclusively on its leader’s appeal. It also depends on it improving its organisational structure — that is, ceasing to be a personal party. For the time being, there is no figure within Chega that comes close to Ventura in terms of appeal and rhetorical skill. Though this could be a symptom of the party’s youthfulness, it is in clear contrast to, for example, Vox in Spain – another relatively new radical right party, which has several figures that recurrently appear next to the party’s leader, Santiago Abascal, and take turns with him in the party’s external political communications. Chega, meanwhile, remains the André Ventura show.

This piece of original analysis for the Populism in Action Project, is a guest post kindly written by Dr. Mariana S. Mendes of the Dresden Technical University. Her PhD on “Delayed Transitional Justice: Accounting for Timing and Cross-country variation in transitional justice trajectories” was awarded by the European University Institute in 2019. You can follow Mariana on Twitter here.