‘Standing on the verge of another world’: Romanticism on the Volcano

With guest speaker Professor Simon Bainbridge

Seminar

Wednesday 19th March, Arts Building, University of Birmingham, Arts Room 201, 3-5pm

Arts of Place is delighted to welcome Professor Simon Bainbridge expert in Romanticism, the politics of place and mountaineering in this seminar hosted in collaboration with the Nineteenth Century Centre at the University of Birmingham. Simon will give his talk during the first hour; followed by refreshments and conversation.

Simon Bainbridge is a Professor in English and Creative Writing at the University of Lancaster. Simon’s extensive work in the field of Romanticism has involved close research into the relationship between the movement and the historic contexts that surround it. He is the author of Napoleon and English Romanticism (1995) and British Poetry and the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (2003). In this seminar we will hear about Simon’s recent research exploring global mountaineering in the Romantic-period, focusing on accounts of ascending Hawaii’s highest volcanoes.

Simon introduces his subject here:

‘This paper will examine the Romantic-period phenomena of global mountaineering through a focus on accounts of the climbs of Hawaii’s highest volcanoes (Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea). These climbs by western travellers began in 1779 with attempts made by crew members of Captain Cook’s third voyage and culminated in 1840-1 with a 400-strong ascent made by the United States Exploratory Expedition as part of the first American government sponsored scientific expedition to the Pacific. As these contexts would suggest, the ascents were very much linked to the scientific and imperial agendas of the voyages of which they were a part. The paper will examine the extent to which the exploration of what were seen as physical, psychological, geographical and imaginative extremes in Romantic-period global mountaineering undermined or reinforced the climbers’ conceptions of the self, the aesthetic, the world and the divine. It will particularly examine the question of whether western climbers’ attempts to understand and appreciate the Hawaiian volcanoes were influenced and informed by the knowledge and beliefs of the indigenous peoples who played such a crucial role in their ascents or whether the western climbers used their ascent narratives to reinforce wider imperial and colonial power structures.’

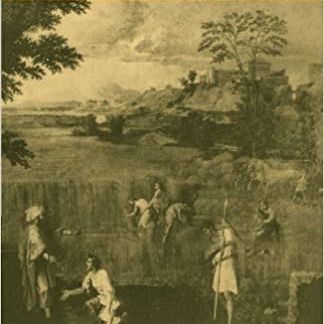

Image: Johan Christian Dahl, Eruption of Vesuvius, 1826, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

From the cliffs of Dover to the industrial city of Manchester, Readman highlights the significance of connections between landscape and heritage in the construction of a modern, popular form of English national identity. This work explores how landscapes are ‘storied’ with countless human histories and memories bound up with place. Through the history, literature and art of the late eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, Storied Ground traces a varied and widespread engagement with landscapes in English culture. Expanding a marginal, conservative and anti-modern understanding of rural Englishness, Readman demonstrates how a ‘topography’ of English national identity accommodated industrial landscapes and diverse political perspectives in a rapidly urbanising and democratising modern Britain.

From the cliffs of Dover to the industrial city of Manchester, Readman highlights the significance of connections between landscape and heritage in the construction of a modern, popular form of English national identity. This work explores how landscapes are ‘storied’ with countless human histories and memories bound up with place. Through the history, literature and art of the late eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, Storied Ground traces a varied and widespread engagement with landscapes in English culture. Expanding a marginal, conservative and anti-modern understanding of rural Englishness, Readman demonstrates how a ‘topography’ of English national identity accommodated industrial landscapes and diverse political perspectives in a rapidly urbanising and democratising modern Britain.

This book provides a useful way to conceptualise the differing scales of British and American landscapes in the context of nature writing from the nineteenth century to the twentieth century. Hooker suggests that many British writers demonstrate ‘ditch vision’ in their portrayals of environments. Rather than grand expanses, this approach studies microcosms of the wild in landscapes otherwise deemed increasingly urban. Hooker takes his lead from Richard Jefferies who in ‘The Pageant of Summer’ finds a ditch overflowing with ‘Green rushes, long and thick … the white pollen of early grasses … hawthorn boughs … briars … buds’ ([1884] 2011: 41–2). The observation leads him to remark, ‘So much greater is this green and common rush than all the Alps’ (ibid.: 43). Hooker applies his concept of ‘ditch vision’ to writers including Edward Thomas, John Cowper Powys and Frances Bellerby.

This book provides a useful way to conceptualise the differing scales of British and American landscapes in the context of nature writing from the nineteenth century to the twentieth century. Hooker suggests that many British writers demonstrate ‘ditch vision’ in their portrayals of environments. Rather than grand expanses, this approach studies microcosms of the wild in landscapes otherwise deemed increasingly urban. Hooker takes his lead from Richard Jefferies who in ‘The Pageant of Summer’ finds a ditch overflowing with ‘Green rushes, long and thick … the white pollen of early grasses … hawthorn boughs … briars … buds’ ([1884] 2011: 41–2). The observation leads him to remark, ‘So much greater is this green and common rush than all the Alps’ (ibid.: 43). Hooker applies his concept of ‘ditch vision’ to writers including Edward Thomas, John Cowper Powys and Frances Bellerby.

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by