As part of our celebrations at the close of the first year of Arts of Place, we are delighted to welcome leading land artist Julie Brook as our Artist in Residence. Here, we look over Brook’s career and work.

Brook is a British artist who creates large scale sculpture. She uses a variety of natural materials and incorporates photography and film to combine wild terrains with classical formalism. Drawing from, with, and in the landscape, Brook has lived and worked in the Orkney Islands, on Jura and Mingulay, and in the Libyan desert. She currently lives on the Isle of Skye.

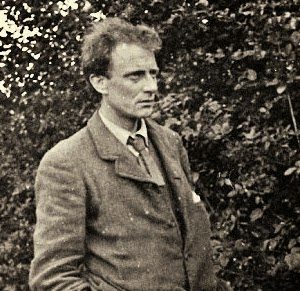

Artist Julie Brook, pictured near her home on Skye. PIC Jane Barlow/TSPL.

Brook travels to and dwells within remote regions, spending time inhabiting the landscape either alone or with local guides. These places are usually quite solitary and inhospitable, from caves in the Hebrides to Libyan deserts. From there she makes art that reconnects us with the natural world, in exciting ways, through sculpture and large-scale drawing. From 1989 Julie Brook has been living and working in remote landscapes in Scotland: Hoy, Orkney (1989); the west coast of Jura (1990-94); on the uninhabited island of Mingulay (1996-2011) in the Outer Hebrides. Recently she has been working in different parts of the desert: in Central and South West Libya (2008-09) travelling with Tuareg guides; Syria (2010); NW Namibia (2011-14) travelling with Himba-Herero guides; Aird Bheag, Hebrides and Komatsu, Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan (2015-2022).

Pigment Drawing, poured. Otjize, NW Namibia.

In the early nineties, Brook moved to the remote island of Jura on the west coast of Scotland to paint and draw. Living beneath a natural stone arch, the solitude became part of her art. While living alone and collecting water and fuel for drinking and cooking, Brook began to build artworks using materials found on the island. So became her Firestack series, where she used rocks to build cairns on the shore, and wood to set fires in them as the tide came in. Eventually, the stacks toppled, and Brook captured the whole process on film.

“Brook’s Firestacks are works that we feel could have been made at any time in the past 5000 years, but they have had their pertinence refreshed by the current focus we are putting on the environment. When the tide comes in her artwork has to make its own case against the elements, just as we, in the age of dawning climate change, might still have to.” – Jonathan McAloon for Elephant Art

Firestack, Autumn: Aird Bheag, outer Hebrides, 2015.

We are extremely excited to host Brook at Arts of Place this summer. On the afternoon of 23rd June, she will be running a practical drawing workshop for Arts of Place writers and readers. This free workshop will be a chance to explore form and emphasis in a different medium. You can read more about the workshop and reserve your place here.