Martin Stott

Martin Stott

Sustainability campaigner, photographer, local champion, Oxford

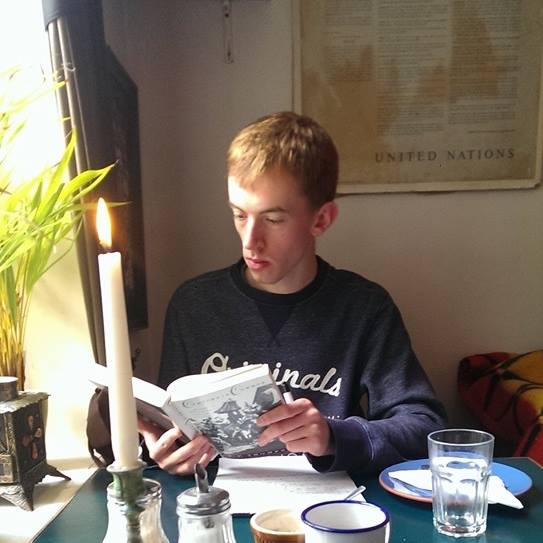

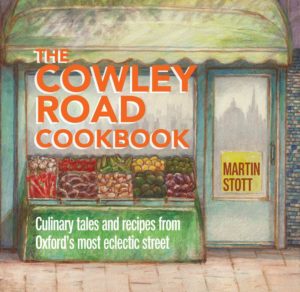

I have worked on sustainable development and regeneration issues in my career in local government, having graduated from Oxford in geography and LSE in town and country planning. I am now a writer and photographer documenting the granular and quotidian characteristics of small spaces and the people who live in them – particularly in east Oxford, where I have lived for the past 40 years. My book The Cowley Road Cookbook: culinary tales and recipes from Oxford’s most eclectic street (Signal Books, 2015) documents the social and cultural history of one street through food, from the twelfth century to the present day. I blog as ‘Lord Muck’ in a fairly light-hearted manner on gardening, growing, cooking, composting and other aspects of our interaction with the natural world.

I have explored William Morris’s experience of, response to, and continuing impact on Iceland in ‘What came we forth for to see that our hearts are so hot with desire: Morris and Iceland’ in The Routledge Companion to William Morris (ed. Florence Boos; Routledge, 2021).

I have been working since mid-2018 on a project to record every household on the street I have lived on for the past 33 years, in the Divinity Road Photo Project. The street is very long, very diverse and very transient, and has been identified as the street with the widest range of household incomes in England. The COVID-19 pandemic has reframed and refocussed the project in a context where our understanding of neighbourhoods has become ever more important.

“Divinity Road has been identified as the street with the widest range of household incomes in England”

Explore Martin’s Work

The Divinity Road Photo Project

The Routledge Companion to William Morris

(Oxford, 2010)

(Oxford, 2010)

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by