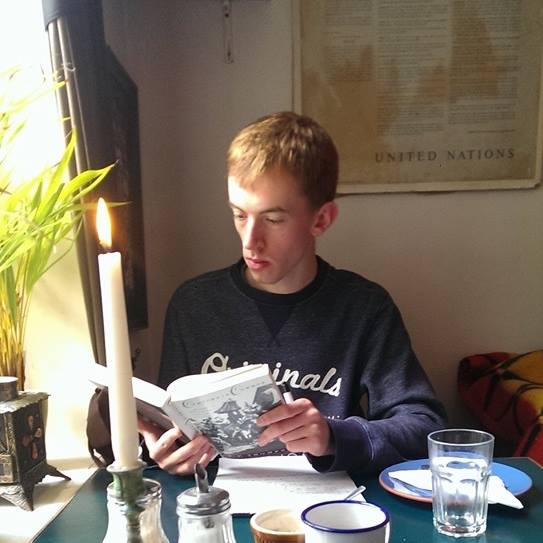

James Metcalf

James Metcalf

Lecturer in Eighteenth-Century Literature, King’s College London

https://www.kcl.ac.uk/people/james-metcalf

Often called the ‘graveyard school’, but more specifically focussed on the churchyard, the poets I work on begin their poems with a strong attachment to place. As the centre of British rural life for centuries, the material place of the country churchyard kept the ancestral dead at the foundation of a local, living community. It was also a prominent symbolic space in the cultural imaginary, defining the inherited, intergenerational relationship between the living and the dead. During the eighteenth century, the country churchyard’s significance was continually reaffirmed in poems that were attentive to both its physical landscape and its emblematic position at the intersection of nature, history, death, and the sacred.

My book project, provisionally entitled Written in the Country Churchyard: Place and Poetics, 1720–1820, refocuses critical debate on poems by Thomas Parnell, Edward Young, Robert Blair, and Thomas Gray, but also an expanded range of texts including poems by Elizabeth Carter, William Cowper, Charlotte Smith, William Wordsworth, and John Clare. I use the country churchyard topos inhabited by these poems to examine how this place was not a formulaic backdrop for melancholy mood-pieces, but a central site for their contemplative poetics. My project also includes a special issue of the European Journal of Life Writing (2020) with an essay on the dramatic revisions to ‘graveyard school’ formulations of the dead, place, and community in Charlotte Smith’s ‘Sonnet XLIV. Written in a Church-Yard at Middleton in Sussex’ (1789) and a forthcoming chapter on Elizabeth Carter’s ‘Ode to Melancholy’ (1739), interrogating the role of the churchyard in Carter’s negotiation of ideas of active sociability and contemplative solitude.

This work is constellated around eighteenth-century preoccupations with the body and its relationship to the phenomenal environment, drawing on themes including landscape and the earth, the body and labour, and self-reflexive attention to the procedures of poetic making that cross the boundaries of physical and cognitive dwelling in a simultaneously real and imagined place. These ideas continue to animate my research, including a new project on eighteenth-century poetry and the objects unearthed, collected, and interpreted in contexts of geology, natural history, and antiquarianism. I am exploring how materials such as fossils, bones, fragments of rock strata, and made artefacts were ‘unearthly’ in a layered sense: extracted from the earth, they also stimulated both estrangement and excitement in their unknown origin, composition, and relation to the history of the earth. At the centre of geohistorical inquiry, these unearthly objects were also a source of imaginative vitality for poets in this period. I am reading their work to investigate how these materials test the limits of literary representation and compel new forms of thinking and writing about the nonhuman—an issue made urgent and compelling in our Anthropocene epoch.