A few summers ago, I was standing on a coal spoil in South Wales, overlooking the derelict structure of the Cwm Coking Works. I was there with Liam Olds, a young entomologist who specialises in the insect life of former collieries. ‘People see these places as eyesores,’ he said, ‘but they’re so much more than that. For animals, they’re a kind of shelter — a refuge from monoculture farms, conifer plantations and fragmented habitats. They’re important ecosystems in their own right. It just takes some time before you begin to see them.’

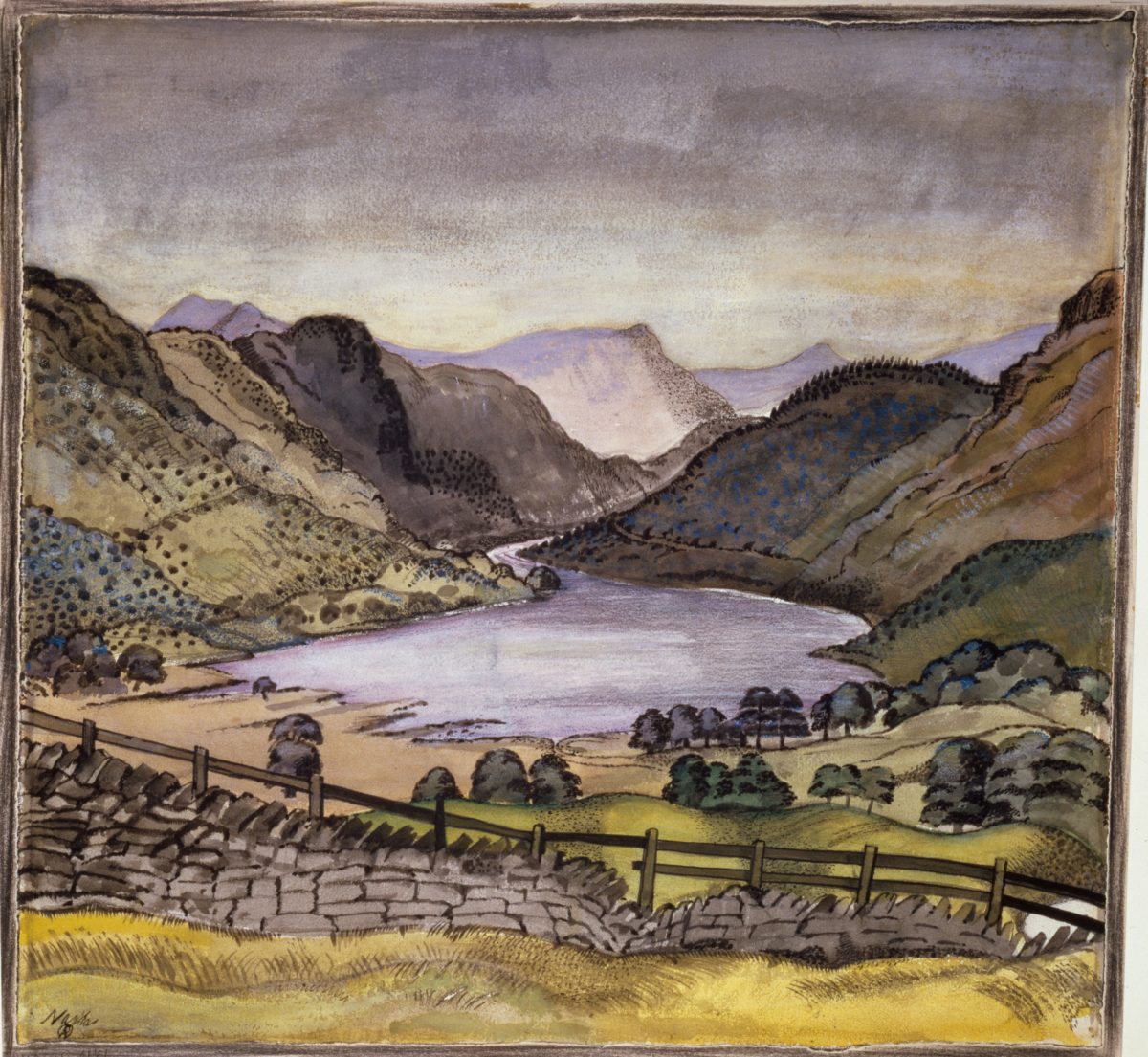

‘How do you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?’ Meno asked Socrates. It is also a question for our times. Without any of our interference, and without any of our planning, some of the landscapes we call wastelands have become difficult paradises. They are places where life is learning to thrive again, but they are difficult because they do not conform to our ideas of what healthy landscapes might look like. The miners who scooped coal from deep inside the Welsh earth brought other things to the surface, among them clay, shale, sandstone, and ironstone. The materials were piled up in the most haphazard ways, first in little hillocks, and later, as the mining continued, into landscape-defining hills. Limestone mixed with shale, sandstone was thrown up alongside clay, and the stratigraphy of the earth, which had been gradually laid down over millions of years, and which ran in large folds and faults beneath us, came to be mixed in the strangest proportions.

What followed was bizarre, wild, unpredictable. The spoil heaps formed complex topographies of their own, characterised by varying gradients and aspects, and because the spoils were composed of different materials, with different pH levels and soil structures, they provided the underlying substrate for different landscapes to emerge. During my tour of the spoils, I saw more distinctive habitats in two hours than I usually do over a day of walking. There were bilberry-filled heaths next to wildflower meadows; patches of open, free-draining ground next to bristling reed beds; woodlands next to boggy marshes; and, on the other side of the spoils, what Liam called ‘inland sand dunes’, habitats usually formed by wind, but which emerged here under less natural conditions.

The habitats were home to a bewildering diversity of plants. On some slopes we found carline thistles, which thrive in calcareous soils, and the low-lying fields were filled with undergroves of bird’s-foot-trefoil and kidney vetch. Nearby we found southern marsh orchids, a plant of damp alkaline meadows, and, half a mile away, round-leaved wintergreens, a plant that typically grows on coastal dunes. And interspersed among these plants were a variety of moss and lichen species, including greasewort, Clay Earth-moss, Olive Beard-moss, and Whorled Tufa-moss. ‘The soil here is nutrient-poor’, Liam explained, ‘which is why these plants are here. They thrive in the stressed ground conditions left behind by the spoils. In fact, the more stressed the ground is, the more flowers they seem to produce.’

With the greenery came the insects. There were dingy skippers and graylings, mottled grasshoppers and meadow grasshoppers, dozens of bee species, as well as dragonflies the size of my hand. And, amongst this heady mix, there were the parasites: specialist hoverflies that preyed on a particular kind of ant, flies that preyed on beetles and moths, and a wasp that preyed on certain miner bees. (Later in the day, as Liam pointed out a miner bee’s burrow, the wasp he was talking about appeared right on cue, a yellow flash in the air.) Some of the creatures recorded here are common to Britain, others are nationally scarce. Others still are new to science, including a millipede Liam’s friend found on the Maerdy colliery spoil, duly named the ‘Maerdy monster’. And here they all were, the rare and the abundant, sharing the strange commonlands of the spoils. Since 2015, Liam has found more than 900 invertebrate species on the coal tips, but there are many more surveys to conduct, and he suspects his list will grow substantially in the years to come.

‘too ugly to care for…’

No-one knew these spoils would be so accommodating to wild life. Inadvertently, the impoverished landscapes left behind by mining generated pockets of richness. Wildflowers that could no longer be found on intensive farmland began appearing here, followed by beetles and bees, moths and butterflies. Some of these abandoned collieries are among the most successful rewilding projects that have taken place in Britain, although they have never been seen or described as such. People find them too ugly to care for, and today hundreds of spoil tips are threatened by reclamation projects, including proposals to ‘green’ the spoils. Liam shudders at the misnomer. He wants them recognised as sites of special scientific interest.

Some of the places we have spoiled will never heal again, at least in our lifetimes. The barn swallows of Chernobyl continue to be born with strange malformations — misshapen beaks, bent tail feathers, crippled toes — while open-cast mines in Appalachia have completely terraformed the geology of the earth. But if many landscapes are in need of healing, there are also those places that have found their way back to health, although not in ways we intended or planned. They rebuke us with their strength, but also educate us with their presence, reminding us of the vitality that can sometimes emerge from damaged places. We should celebrate them, too, not in order to excuse destruction, or to uncritically celebrate nature’s ‘resilience’, but to appreciate what happens when we stand to one side. The Latin term relinquere gives us the adjective ‘derelict’, a word for forsaken and abandoned things, and it also gives us the verb ‘relinquish’, to give up or desist from. Not all derelictions are bad, and some of our plundered places can come good again. We do not necessarily have to withdraw from these places, but rather inhabit them more skilfully and on different terms. Liam has taken up a family tradition — both his grandfather and great-grandfather were coal miners — but he works the land in a very different way now, noticing rather than extracting, and standing aside rather than digging down.

Michael Malay is a Lecturer in English Literature and Environmental Humanities

at the University of Bristol