In the year of Wordsworth’s 250th birthday, Jessica Fay shows how Wordsworth responded to the craze for picturesque garden ruins and his affirmation of the slower, quieter stories of lives and places that ruins can evoke.

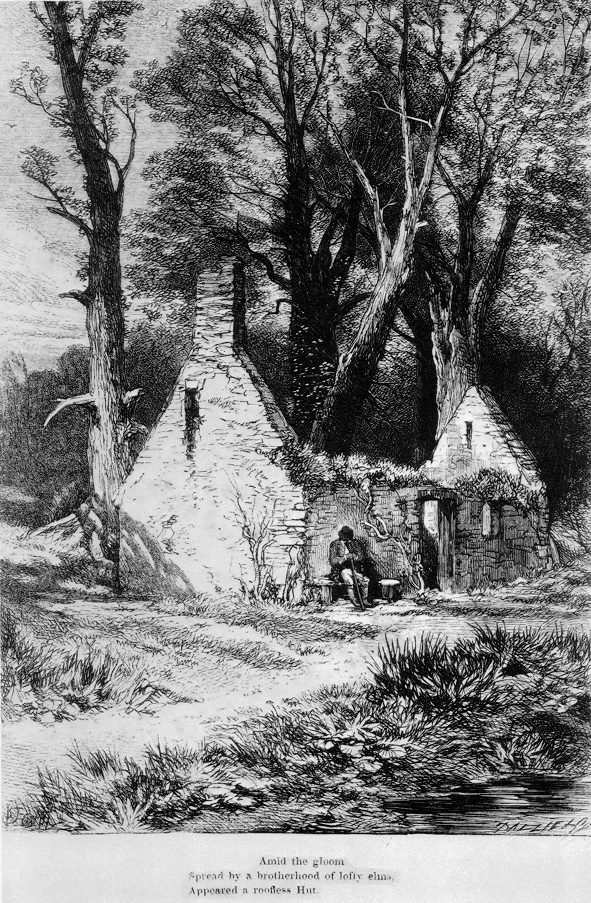

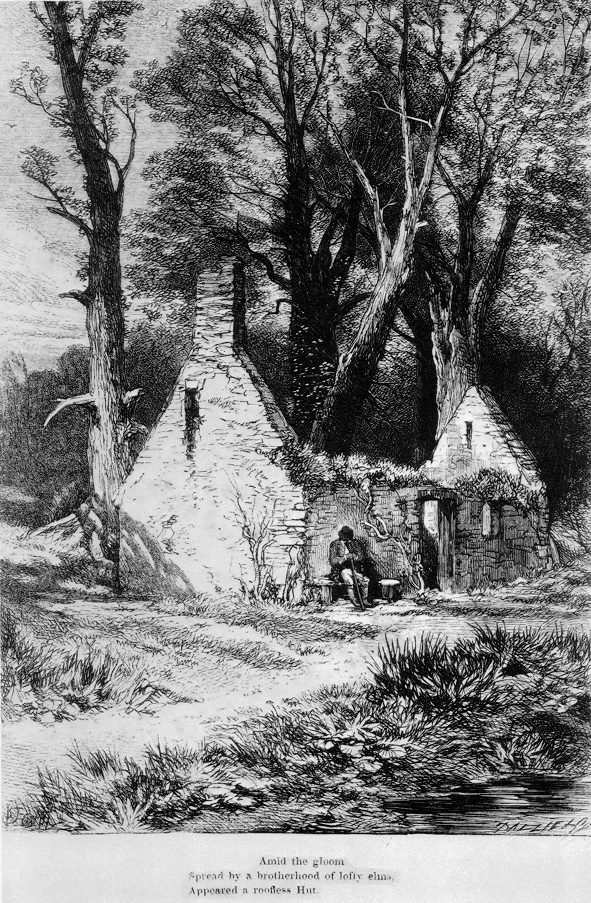

Myles Birket Foster’s frontispiece to William Wordsworth, The Deserted Cottage (1859) engraved by the Brothers Dalziel.

Imagining William and Dorothy Wordsworth out walking in the Lake District might involve thinking of them closely observing their surroundings, commenting on what they notice, talking about local news or Napoleon’s most recent campaign, or reciting poetry. We might imagine them pausing to refresh themselves with cold beef or leftover gooseberry pie that they carried in their pockets. But we might not think of them pausing to take out a tinted Claude Glass.

The fashionable activity of ‘picturesque tourism’, made popular by William Gilpin’s guidebooks of the 1780s and 90s, involved observing natural scenery through a small glass mirror or an imaginative filter. The mild absurdity of this practice of re-tinting and rearranging what was actually visible in a landscape is emphasized by a quip of Jane Austen’s in Northanger Abbey (composed 1798–99), where Henry and Isabella Tilney view ‘the country with the eyes of persons accustomed to drawing’ and proceed to decide its ‘capability of being formed into pictures’ (with a pun on the nickname of fashionable landscape gardener Lancelot “Capability” Brown). The heroine, Catherine Morland, is considered ironically to be without ‘natural taste’ until she’s been instructed in picturesque principles.

Wordsworth intimates his opposition to the picturesque in Book XI of The Prelude (1805), where he describes the habit of looking at nature through the lens of art as ‘a strong infection of the age’. He objected to landscape appreciation in which ‘the eye [is] master of the heart’ and where insufficient attention is paid to ‘the moods | Of nature, and the spirit of place’. Although Gilpin and his followers recognised the importance of felt responses to scenery, picturesque tourism seemed (to the poet) to commodify nature. But the Wordsworths did own a Claude Glass and William’s engagement with the picturesque—as a gardener as well as a poet—was deep and considered.

In his Guide through the District of the Lakes (first published in 1810), Wordsworth sets out a key principle for gardening: ‘The rule is simple; with respect to grounds—work, where you can, in the spirit of nature, with an invisible hand of art’. This might appear to be an endorsement for the style of gardening initiated by William Kent at Stow in the 1730s, which helped catalyse the craze for all things ‘picturesque’. Kent’s invention of the ha-ha (or sunken fence) made it possible to conceal boundaries between a cultivated garden and the landscape beyond. In Kent’s sweeping open prospects, the ‘hand of art’ was far less visible than it had been when parterres and topiary were the order of the day. Yet Wordsworth agreed with gardeners such as Uvedale Price (whose Essay on the Picturesque was first published in 1794) that the conventions established by Kent, Brown, and their followers came to be applied too mechanically. Since features such as serpentine lakes, trees arranged in clumps or belts, temples, hermitages, or follies were so recognisable, the artifice of landscape gardening was in fact obvious. Disregarding the idiosyncrasies of a given place, these “improvers” often overlooked ‘the spirit of nature’.

In particular, Wordsworth agreed with Price that ‘improvers’ paid too little attention to timeworn characteristics such as ancient trees and dilapidated stonework. But Wordsworth and Price appreciated these rugged features for different reasons. For Price, any object is picturesque if it bears three specific visual qualities: roughness, sudden variation, and irregularity. Ruins of different kinds—the remains of once-consecrated monasteries, crumbling manor houses, mouldy humble cottages, or even purpose-made follies—are equally admirable when they exhibit these qualities. Wordsworth, by contrast, didn’t primarily value ruins for their surface appearance: he was less interested in form and texture and more concerned with the personal or communal histories attached to these objects. The ruins of medieval monasteries such as Tintern, Furness, and Bolton, were important as loci of regional heritage; the ruins of secular dwelling places similarly offered, for Wordsworth, means of connection with previous inhabitants through an experience of place. Importing faux ruins or follies into gardens as picturesque props—and for the sake of fashion—bypassed any such place-centred human connection.

In particular, Wordsworth agreed with Price that ‘improvers’ paid too little attention to timeworn characteristics such as ancient trees and dilapidated stonework. But Wordsworth and Price appreciated these rugged features for different reasons. For Price, any object is picturesque if it bears three specific visual qualities: roughness, sudden variation, and irregularity. Ruins of different kinds—the remains of once-consecrated monasteries, crumbling manor houses, mouldy humble cottages, or even purpose-made follies—are equally admirable when they exhibit these qualities. Wordsworth, by contrast, didn’t primarily value ruins for their surface appearance: he was less interested in form and texture and more concerned with the personal or communal histories attached to these objects. The ruins of medieval monasteries such as Tintern, Furness, and Bolton, were important as loci of regional heritage; the ruins of secular dwelling places similarly offered, for Wordsworth, means of connection with previous inhabitants through an experience of place. Importing faux ruins or follies into gardens as picturesque props—and for the sake of fashion—bypassed any such place-centred human connection.

An entry in Dorothy’s Alfoxden journal from April 1798 provides an example of what the siblings considered a misuse of garden-ruins. Dorothy describes a visit to Crowcombe Court in the Quantocks where she explored a garden laid out by John Bernard (son-in-law of the owner Thomas Carew) in the 1770s:

A fine cloudy morning. Walked about the squire’s grounds. Quaint waterfalls about, where Nature was very successfully striving to make beautiful what art had deformed—ruins, hermitages, &c., &c. In spite of all these things, the dell romantic and beautiful, though everywhere planted with unnaturalised trees. Happily we cannot shape the huge hills, or carve out the valleys according to our fancy.

The ruins at Crowcombe were fifteenth-century fragments of stone arches transplanted from nearby Halsway Manor, perhaps arranged to evoke contemplation or melancholy, or to give the Court (built in 1725) an air of antiquity. When Dorothy complains that Bernard has deformed nature, she recognizes that the ruins don’t belong there and is thankful that nature is visibly pushing back against the interfering ‘hand of art’.

A more complex example of nature counteracting cultivation is worked out in Wordsworth’s The Ruined Cottage. First composed at Alfoxden in 1797, the poem underwent several stages of revision before being published as the first book of The Excursion (1814). If it had appeared under its original title at the end of the 1790s, however, that title would have raised specific expectations. For readers well-acquainted with picturesque aesthetics, The Ruined Cottage promises riches: perhaps the poem will focus on quaint ruins like those commonly found in landscape paintings or used as garden ornaments? The opening lines, which describe the effect of ‘steady beams’ of sunshine on an expansive landscape, might also have encouraged readers to think they’d embarked on a conventional eighteenth-century prospect poem. But Wordsworth quickly subverts, or rather deepens, these expectations. As the cottage and its garden are placed in the context of the suffering of their inhabitants, the poem becomes a critique of purely visual, surface appreciation of ruins.

The Ruined Cottage narrates a meeting between a Poet and a Pedlar beside the dilapidated cottage of a woman named Margaret. As they look at the ruin, the Pedlar explains Margaret’s history. Following failed harvests, illness, and loss of work Margaret’s husband, Robert, was forced to enlist. She was left alone with two children and became increasingly despondent as she failed to discover news of Robert’s whereabouts or welfare. Under the weight of poverty, desolation, and loneliness, during a time of deprivation and war, Margaret neglected to take care of herself, her children, the cottage, and the garden. At length she was deprived of both children and of all hope that Robert would return; after five years of suffering, Margaret died.

At the start of the poem, the Pedlar and the Poet survey the deserted cottage and garden:

It was a plot

Of garden-ground, now wild, its matted weeds

Marked with the steps of those whom as they pass’d,

The goose-berry trees that shot in long lank slips,

Or currants hanging from their leafless stems

In scanty strings, had tempted to o’erleap

The broken wall. Within that cheerless spot,

Where two tall hedgerows of thick willow boughs

Joined in a damp cold nook, I found a well

Half-choked [with willow flowers and weeds.]

I slaked my thirst and to the shady bench

Returned, and while I stood unbonneted

To catch the motion of the cooler air

The old Man said, “I see around me here

Things which you cannot see: we die, my Friend,

Nor we alone, but that which each man loved

And prized in his peculiar nook of earth

Dies with him or is changed, and very soon

Even of the good is no memorial left. (ll. 54–72)

At Crowcombe, Bernard’s ruin was installed and positioned for picturesque effect; through later neglect, nature began to counteract the ‘fancy’ of the gardener, and this pleased Dorothy. In The Ruined Cottage, however, any assessment of nature’s reclamation of Margaret’s garden is more complicated. From the Poet’s perspective, this is a scene of deprivation: the garden wall has fallen down, the well is ‘half-choked’ by weeds, the gooseberry bushes are ‘lank’, strings of currants are ‘scanty’; it’s a ‘cheerless spot’ and there are implications of sinfulness and corruption in images of temptation, trespass, and forbidden fruit. The Poet (keen to find compelling material to write about) is inclined to indulge in the melancholy atmosphere. Yet the Pedlar sees things differently.

One reason why the Poet doesn’t see what the Pedlar sees is that, at this point, he hasn’t heard Margaret’s story. As the poem progresses, the Pedlar peels back layers of time and memory, revealing how the stages of Margaret’s emotional deterioration contributed to the development of the ruin. By the end of the poem, the tumbledown cottage and overgrown garden bespeak Margaret’s decline, and thus the Poet’s perception is changed: he doesn’t now appreciate the ruins for their picturesque form and texture (as Uvedale Price might have done) but rather for their human context. As Dorothy noted at Crowcombe, ruins are not moving in themselves; but the ruined cottage has a profound emotional effect on the Poet when history, imagination, and empathy are added to his visual experience.

The poem concludes, however, with the Pedlar asking the Poet not to indulge in the sadness of the scene but to walk away in calm happiness:

“My Friend, enough to sorrow have you given,

The purposes of wisdom ask no more;

Be wise and cheerful, and no longer read

The forms of things with an unworthy eye.

She sleeps in the calm earth, and peace is here.

I well remember that those very plumes,

Those weeds, and the high spear-grass on that wall,

By mist and silent rain-drops silver’d o’er,

As once I passed did to my heart convey

So still an image of tranquillity,

So calm and still, and looked so beautiful

Amid the uneasy thoughts which filled my mind,

That what we feel of sorrow and despair

From ruin and from change, and all the grief

The passing shews of being leave behind,

Appeared an idle dream that could not live

Where meditation was. I turned away

And walked along my road in happiness”. (ll. 513–24)

Wordsworth’s thinking about picturesque aesthetics helps explain these moving, yet difficult, lines. One of the purposes of the poem is to teach the Poet to be serene in the face of suffering and change: the extra unstressed syllable at the end of the first line denotes the cusp of what is ‘enough’. Ruins make visible processes of decay but they also reveal nature’s regenerative powers. As Margaret finds ultimate harmony with—and within—the earth (‘She sleeps in the calm earth, and peace is here’), the pace of the verse slows. The Pedlar recognizes that the tranquillity of nature endures, whereas grief is alleviated by time. The survival of the spear-grass and the sustained life and beauty of the garden, channelled through memory and expressed within an elongated sentence that entwines visual with interior experience, provide lasting consolation. The Pedlar’s speech affirms that poetry, and the empathy it produces, helps readers to apprehend the significance beneath the surface; reading ‘the forms of things’ more worthily involves attending to art and nature with an eye that is not ‘master of the heart’. Visual apprehension is transformed when it is supplemented with an underlying sense of what a place has meant to—and what it says about—the people connected with it. Picturesque gardening that clears away knotted or uneven features produced by the slow passage of time (in favour of smooth man-made lines) lacks these submerged human resonances.

Looking through a Claude Glass is, in this way, a less worthy (that is to say, less poetic) mode of viewing. But, for Wordsworth, shaping nature into art has its benefits, too. While the Wordsworths’ Claude Glass may have helped them to reimagine the landscape in a moment (perhaps between bites of cold gooseberry pie), practical gardening works with nature to produce visual and emotional effects over time. ‘Laying out grounds’, William once explained, ‘is some sort like Poetry and Painting, and its object … [is] to assist Nature in moving the affections’. But, he continued, ‘If this be so when we merely put together words or colours, how much more ought the feeling to prevail when we are in the midst of the realities of things’. Gardening that balances the ‘spirit of nature’ with the ‘hand of art’ is itself a kind of poetry; or, we might say, an art of place.

In particular, Wordsworth agreed with Price that ‘improvers’ paid too little attention to timeworn characteristics such as ancient trees and dilapidated stonework. But Wordsworth and Price appreciated these rugged features for different reasons. For Price, any object is picturesque if it bears three specific visual qualities: roughness, sudden variation, and irregularity. Ruins of different kinds—the remains of once-consecrated monasteries, crumbling manor houses, mouldy humble cottages, or even purpose-made follies—are equally admirable when they exhibit these qualities. Wordsworth, by contrast, didn’t primarily value ruins for their surface appearance: he was less interested in form and texture and more concerned with the personal or communal histories attached to these objects. The ruins of medieval monasteries such as Tintern, Furness, and Bolton, were important as loci of regional heritage; the ruins of secular dwelling places similarly offered, for Wordsworth, means of connection with previous inhabitants through an experience of place. Importing faux ruins or follies into gardens as picturesque props—and for the sake of fashion—bypassed any such place-centred human connection.

In particular, Wordsworth agreed with Price that ‘improvers’ paid too little attention to timeworn characteristics such as ancient trees and dilapidated stonework. But Wordsworth and Price appreciated these rugged features for different reasons. For Price, any object is picturesque if it bears three specific visual qualities: roughness, sudden variation, and irregularity. Ruins of different kinds—the remains of once-consecrated monasteries, crumbling manor houses, mouldy humble cottages, or even purpose-made follies—are equally admirable when they exhibit these qualities. Wordsworth, by contrast, didn’t primarily value ruins for their surface appearance: he was less interested in form and texture and more concerned with the personal or communal histories attached to these objects. The ruins of medieval monasteries such as Tintern, Furness, and Bolton, were important as loci of regional heritage; the ruins of secular dwelling places similarly offered, for Wordsworth, means of connection with previous inhabitants through an experience of place. Importing faux ruins or follies into gardens as picturesque props—and for the sake of fashion—bypassed any such place-centred human connection.