Mattia Zulianello (PiAP’s Italy focused Research Fellows) talks with Political Observer about populist parties and how they integrate into the systems of their respective countries, even as they present themselves as anti-elitist?

PO: In your study, you calculate that in Europe 2/3rds of contemporary populist parties are integrated in their political systems, while only 1/3rd are relegated to the margins. Is it possible to claim that populist parties are the “new normal”? And how can you explain that populism relies on anti-elitist concepts while being part of the political system?

MZ: To some extent, yes: populist parties are the “new normal”.

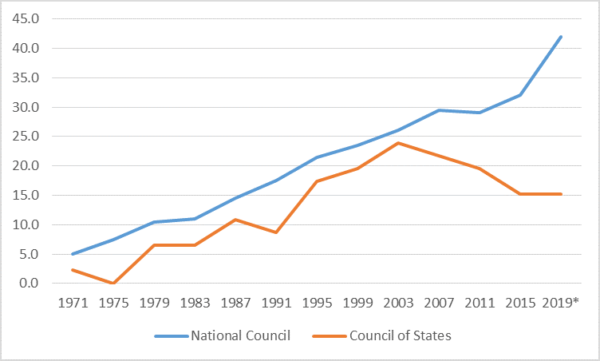

In many countries, populist parties are required to give life to governmental majorities. Once favorable political conditions exist, a process of legitimation between the populists and the major non-populist actor(s) can replace years of reciprocal hostility.

This can occur very rapidly. In some countries the populists really dominate the electoral arena, in particular in Italy and Hungary. In others, despite their limited electoral strength – they still dominate the media arena.

So the increasing integration of populist parties into national political systems is part of a broader process of the normalization and legitimation of populism by more “conventional” partisan actors, such as centre-right and centre-left parties, but also in the media and public debate.

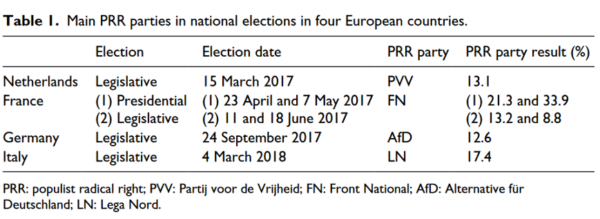

This is particularly evident in the case of populist radical right parties, given the unprecedented importance of nativism in the public debate; in the agendas of more traditional competitors; and even at the European Union level, as shown by the recent controversies over the new portfolio for “protecting our European way of life”.

However, this does not mean that the normalization and legitimation of populism is limited to the right side of the political spectrum. Albeit less evident in comparison with those mobilizing immigration and cultural issues, populist parties of other varieties now set the public agenda in many countries.

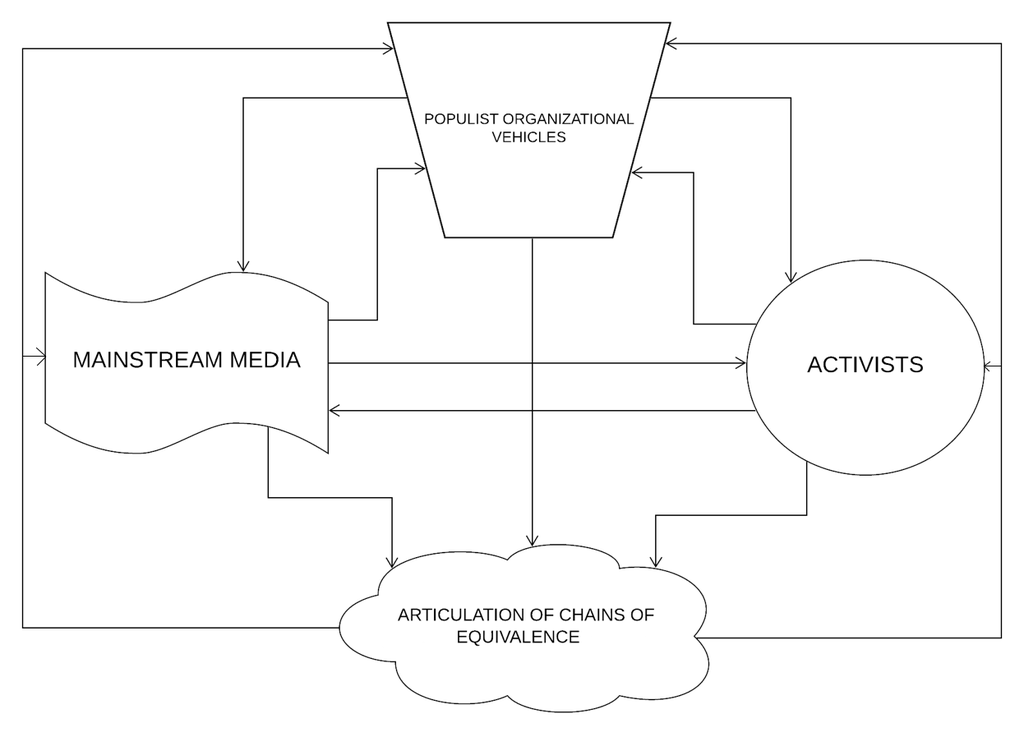

This is due to two major reasons. First, in most cases perception is more important than reality, such as immigration numbers vs. perception of immigration or objective economic indicators vs .the feeling of relative deprivation). Second, the moralistic rather than programmatic emphasis of populism fits well with the insatiable demand for spectacle by journalists in an age of “hybrid media systems“.

Over-representation in the media is precisely what should be avoided, and the strategy of over-demonization does not work either: populists — whether of the right, left, or valence variety — seek media attention, and the media, in most cases, give them exactly what they want. In many cases this is also true of us as political scientists: we ascribe a disproportionate importance to marginal actors and events.

PO: How does populism rely on anti-elitist concepts while being part of the political system?

MZ: Anti-elitism, or an anti-establishment attitude, is a key part of the identity and profile of a populist party. If a populist party ceases to be anti-elitist, it also ceases to be populist.

The key point is how the populists can remain credible in their anti-elitism despite integration. Despite the ongoing parroting of the frames and style of populists in some policy areas by more conventional parties, voters usually prefer the original rather than the copy.

Simply put, anti-elitism needs to be credibly articulated. This is easier when populist parties effectively qualify as anti-system parties and are at the margins. It is less easy when they become “coalitionable”, and it becomes much more complex when they hold national office. However, even though in many cases the policy achievements of populist parties in office are limited, they can remain credible in the electoral market if they preserve organizational cohesion and manage to deliver the image of being “proactive” actors, irrespective of the actual outcomes.

This can be achieved by adopting a narrative such as “We (really) tried to do y, but for x reasons (independent of our control) it was not possible.” This often takes the form of blame-shifting directed against “the elites”, “the deep state”, or “strong powers”.

Paradoxically, this can contribute to the sustainability of anti-elitism, despite the visible integration of populist parties into national political systems. It is shown by the recent strategy adopted by Matteo Salvini following the failed attempt by the Lega to force new elections in Italy, but also by Alexis Tsipras following his U-turn after the 2015 Greek bailout referendum.

It must be emphasized that this strategy works only if the party manages to contain internal conflict and articulate a consistent and clear message to the voters. The latter has been successfully achieved by various populist parties across Europe; however, it is difficult, as shown by the Austrian FPÖ in 2002 or the Greek Orthodox Rally in 2012.

These maneuvers require strategic and leadership skills, but populist parties are increasingly able to cope with the pressures both of cooperation with non-populist parties and of participation in government.

PO: Let’s have a closer look at the 66 parties you identify as populist. Where are they positioned on the left-right political spectrum? And which are those parties that you call “valence populism”?

MZ: Among the 66 parties I analysed in my article, the vast majority can be located on the right-side of the political spectrum (68.2%).

Among this broad category, the most populated sub-group is represented by populist radical right parties (31), followed by national-conservative populists (10), and a few neo-liberal populists (4).

Only 16.7% of contemporary populist parties are found on the left portion of the political spectrum. A tiny majority of them (6) qualify as typical “social populists”, while the others (5) combine socialism with some form of nationalism.

Finally, for the remaining populist actors (15.1%), I introduce the term of “valence populist parties”, building upon the insights of Kenneth Roberts. Such parties are commonly found in Central and Eastern Europe, with prominent examples including GERB in Bulgaria, ANO 2011 in the Czech Republic, and the List of Marjan Šarec in Slovenia.

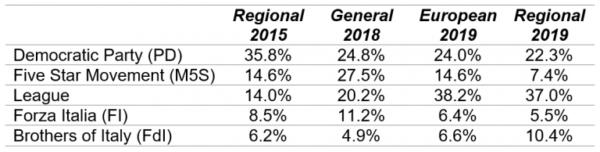

Perhaps the best example is the Five Star Movement (M5S) in Italy. M5S cannot be located in positional terms across the left-right political space, and various studies have outlined its ideological flexibility and eclecticism. The same applies to many parties in Central and Eastern Europe, which, like M5S, over-emphasize non-positional issues such as competence, performance, and anti-corruption.

These features are almost identical to those evoked by the existing definition of a “centrist populist party”, but this is misleading because valence populists lack a clear positioning. Sure, they are not left nor right, but they cannot be located in the “center” either.

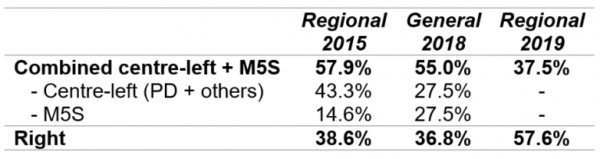

Valence populists may well adopt specific positions. However, in contrast to an unadulterated (or pure) version of populism, positions adopted by parties such as the M5S are flexible, free-floating, often inconsistent, and very much influenced by the structure of political opportunity. M5S’s recent and prompt shift from a government coalition with the populist radical right Lega to one with the center-left Democratic Party provides clear evidence for these features.

PO: When speaking of populism, there is much confusion around terms and definitions. Can you tell us what features distinguish populist parties vis-à-vis anti-establishment, challenger, and outsider parties?

MZ: Well, tons of ink could be spent in reply to this question. To avoid this, I will try to focus on the most important differences, while inviting the reader to see my article for further details.

First, it is very important to underline that none of the three terms are synonyms, even though they are often treated as such. I realized the extreme degree of confusion characterizing the conceptual debate on “anti” during my PhD thesis, which was published as a book by Routledge this year.

Although there are different conceptualizations of the terms “challenger’ and ‘outsider” parties, the most common approaches refer to a specific location of a party in the party system: in the case of the former, the absence of governmental experience; in the latter, the exclusion from the coalition game.

As I highlight in my article, populist parties are not necessarily challengers nor outsiders. On the contrary, around 40% of contemporary populist parties have government experience — and this percentage is rising) — while about 2/3rs are variously integrated in visible cooperative interactions in the political system. This includes, but is not limited to, the ability and willingness to use coalition potential, participation in pre-electoral coalitions, or full participation in national office with the major parties in the system.

Finally, “anti-establishment” depends on how we define the term. If we use it to indicate, inter alia, the unwillingness of a party to cooperate with the “mainstream”, then populist parties are not necessarily anti-establishment; only a minority would qualify as such. However, if we avoid assuming specific behavioral tendencies and use the term to refer only to the ideology of a given party — which is more appropriate, in my view — then populist parties are always anti-establishment in ideational terms, given their emphasis on anti-elitism.

The point is that this ideational orientation is increasingly disjointed from the role of a populist actor in the party system. In other words, for many populist parties, the anti-establishment ideology is not accompanied by an anti-establishment (or uncompromising) behavior.

PO: To go beyond the existing problems with the anti-establishment characteristics of populist parties, you propose a new classification: non-integrated, negatively integrated, and positively integrated populist parties. Which kind of parties belong to the three groups? Why is this classification more precise than previous ones?

MZ: My new classification was inspired precisely by the increasing integration of various types of political parties without the concomitant occurrence of substantial ideological moderation, something that was somehow overlooked in the classical works of Giovanni Sartori.

This led me to the development of a revisited concept of anti-system party. This later served as the foundation for the comprehensive empirical analyses of the challenges faced by such parties that I carried out in my book.

Subsequently, I realized that a fruitful field of application was the comprehensive analysis of the different interaction streams characterizing contemporary populist parties, especially in the light of the terminological and conceptual confusion in the academic debate.

Following Sartori’s classical conception, populist parties — at least in fully liberal-democratic contexts — would qualify by definition as anti-system, given his focus on party propaganda. However, empirical reality suggests that there are huge differences among populist parties in terms of the actual role played in their own national contexts.

Following my conceptualization, I consider anti-system only the populist parties that, in addition to questioning crucial elements of the status quo — most notably the liberal-representative elements of the political regime — are also at the margins of the party system. These are “non-integrated” populist parties, which do not simply challenge the system in ideational terms but also adopt an uncompromising, antagonistic posture vis-à-vis “the system parties”. These represent a systemic constraint, especially in view of a possible extension of the area of government, such as Human Shield in Croatia and the Sweden Democrats.

However, only a minority of contemporary European populist parties are actually anti-system in my conceptualization. The vast majority of them are integrated into the national political systems, meaning that they are involved in important and very visible cooperative interactions at the systemic level, which indicate that they have crossed the threshold of legitimation.

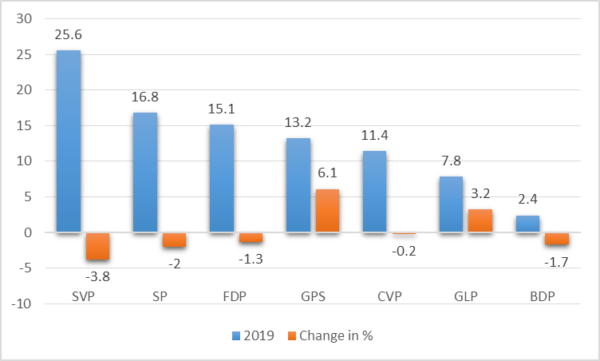

But the integration of populist parties can be either “negative” or “positive”. In fully-fledged liberal democracies, the integration of populist parties is invariably of the “negative” type because, despite their involvement in cooperative interactions, they remain ideologically opposed to one or more key features of the status quo. Commonly, this is the political regime, but in some cases this also encompasses the configuration of the political community or the (capitalist) economic system. Notable examples of negatively integrated populist parties are the Five Star Movement and the Lega in Italy, Podemos in Spain, and the Swiss People’s Party.

On the other hand, in flawed democracies or non-democracies, the integration of populist parties well be of the “positive” type. Given the illiberal nature of such regimes, their ideational profile may be in a symbiotic relationship with the status quo, its values, and practices, as shown in particular by the case of Fidesz in Hungary.

Hence, the utility of my classification is the capacity of distinguishing the very different roles played by populist parties in contemporary party systems, rather than forcing this heterogeneity into over-simplistic assumptions that in the end unrelated to the empirical reality.

For instance, the Lega is a paradigmatic case of a negatively-integrated populist party. However, even though it is the oldest parliamentary party in Italy and has a long record of participation in national governments, it is still considered by some scholars as a “challenger” or “outsider” party…

PO: Talking of positively-integrated populist parties, you write that “in hybrid or fully authoritarian contexts, populist parties may well be ‘positively’ integrated into the system, meaning that they share its underlying values, as shown by the cases of Hungary, Russia and Serbia”. What are the implications of this finding for the future of liberal democracy in Europe, in particular concerning popular sovereignty and pluralism?

MZ: This finding is simultaneously intriguing and disheartening. Whereas the authoritarian nature of the Russian regime is not the consequence of populism, in the cases of Hungary and Serbia the process of de-democratization was actively pursued and achieved by the ruling populist parties: Fidesz and the Serbian Progressive Party, respectively.

As I argue in the article, “these parties changed the sources of legitimation upon which the political regime itself is built”. Clearly, this was decisively favored by the recent democratization of both the countries, but in the case of Hungary this occurred in an European Union member state. This what I find particularly disturbing.

Commenting on the outcome of the 2019 European Parliament elections, Martin Selmayr, then Secretary-General of the European Commission, declared that the “populist wave…was contained”. However, leaving aside that the de-democratization of Hungary would not have been possible without the (in)actions of the European People’s Party, this statement well summarizes the limited vision of non-populist parties and politicians: their focus is placed on short-term electoral. Meanwhile, populism has already profoundly changed the political debate in the EU, and even transformed a country located in the very heart of the European Union into a “(competitive) authoritarian regime”.