Life Through Wax

Beeswax in Ancient Egypt

Zara Shoosmith

The unique physical properties of beeswax; water-resistance, malleability and a low melting point, made it useful to the ancient Egyptians in a number of ways.

Beeswax was used to preserve the curls and plaits in wigs and could be used as a face cream.[1] In medicine it was used as an adhesive for bandages and to bind active ingredients into pills.[2] Boats were waterproofed with beeswax and complex metal shapes were created using the ‘lost wax’[3] casting technique.[4]

|

|

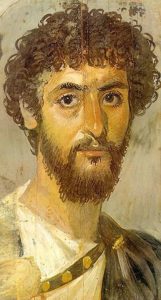

The properties of beeswax also created a number of symbolic associations for the Egyptians. Its malleability made beeswax a perfect metaphor for creation in religious rituals, allowing an individual to embody the god Khnum who modelled life out of clay.[5] Wax could also be used to mimic life-like features such as hair and skin in art.[6] For the Egyptians this reinforced the idea that beeswax was imbued with life-giving properties.

|

|

Papyrus Salt 825 details the way in which ancient Egyptians understood the creation of beeswax and its meaning relating to the sun god, Re;

|

Consequently beeswax was also connected to Egyptian ideas about the sun and its symbolism, further strengthening its associations with new life.

This relationship between the symbolic and practical qualities of beeswax can be seen especially well in the use of beeswax models.

Beeswax models were used for a wide range of religious practices. Some of the best documented are execration rituals.[8] Execration rituals involved the symbolic destruction of an enemy through the actual destruction of an object bearing the enemy’s likeness. The lifelike qualities of wax made it a perfect material for these rituals as models could be made to look as much like the enemy to be destroyed as possible, adding realism and power to the symbolic destruction.

This realism also lent power to beeswax when it was used to symbolise new life. From the New Kingdom into the Third Intermediate Period beeswax benu birds were placed in tombs to encourage rebirth in the afterlife.[9] By the Late Period benu bird moulds with traces of beeswax were also placed in tombs.[10] One of the beliefs held by Egyptians about the benu bird was that its call had summoned life into an empty world of dark waters, tying it to the same ideas of new life and renewal ascribed to beeswax.[11]

|

|

Other wax objects placed in tombs and intended to imbue life to the deceased included amulets such as ankhs made of beeswax and coated in gold. Wax models of the four sons of Horus were also placed in tombs in the Third Intermediate Period when canopic jars became less common.[12] These wax figures served to protect the organs of a mummified individual for use in the afterlife. As with the amulets and the benu bird figures these sets could be produced en masse due in part to wax’s low melting point and malleability. This once again demonstrates the material’s physical properties harmonising with its symbolism.

|

|

The magical applications of beeswax figures are also mentioned in a number of Egyptian texts. In Papyrus Westcar a priest is recorded as bringing a wax crocodile to life to eat his wife’s lover and in papyri Lee and Rollin the suspects in Ramses III’s harem conspiracy are accused of making wax models to ‘disable and enfeeble the limbs’.[13]

Beeswax would therefore have been a common sight in Egyptian life, in religion, in medicine, in shipbuilding, beauty, magic and art. Its properties made beeswax useful in a wide range of industries but also imbued it with special meaning focusing on life and vitality. Consequently the symbolic applications of beeswax can be seen to have been as real to the Egyptians as their practical uses without one ever belittling the other. This allowed beeswax to exist as both a material to be used and respected as a substance with special meaning depending on the situation. Consequently it existed simultaneously as a special and a ubiquitous part of Egyptian life.

[expand title=”Endnotes”]

[1] Lucas and Harris 2000: 336-337; Kritsky 2015: 107.

[2] Kritsky 2015: 91.

[3] Lost wax casting involves the making of a wax model which is eventually melted away leaving a metal duplicate. As wax is easier to sculpt than metal more detailed works could be produced with this method. See Norton 2016 for examples of lost wax objects.

[4] Kritsky 2015: 106.

[5] Pinch 1994: 81; Pinch 2002: 153.

[6] One such process, called ‘encaustic painting’ was brought to Egypt in the Greco-Roman Period. It involved mixing pigments with wax and using tools to texture the resulting painting.

[7] Leek 1975: 148.

[8] See Faulkner 1937; Fermat 2010.

[9] Kritsky 2015: 112.

[10] Raven 2012: 147.

[11] Pinch 2000: 59-60.

[12] Pinch 1994: 99-100.

[13] Teeter 2011: 165; Leek 1975: 145.

[/expand]

[expand title=”Bibliography and Further Reading”]

Faulkner, R.O. 1937. ‘The Bremner-Rhind Papyrus: III: D. The Book of Overthrowing ‘Apep’. The Journal Egyptian Archaeology 23 (2), 166-185.

Fermat, A. 2010. Le Rituel de la Maison de Vie: Papyrus Salt 825. Paris.

Georganteli, E. and M. Bommas. 2010. Sacred and Profane: Treasures of Ancient Egypt form the Meyers Collection, Eton College and University of Birmingham. London.

Kritsky, G. 2015. The Tears of Re: Beekeeping in Ancient Egypt. Oxford.

Leek, F.F. 1975. ‘Some evidence of bees and honey in ancient Egypt’. Bee World 56 (4), 141-148.

Lucas, A. and J.R. Harris. 2000. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries. New York.

Norton, B. 2016. “Gifts for the Gods: Animal Votives and Mummies in Ancient Egypt”, in S. Boonstra (ed.), Objects Come to Life, Birmingham Egyptology.

https://more.bham.ac.uk/birminghamegyptology//virtual-museum/objects-come-to-life/gifts-for-the-gods/

Pinch, G. 1994. Magic in Ancient Egypt. London.

Pinch, G. 2000. Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. Santa Barbara.

Serpico, M. and R. White. 2000. ‘Oil, fat and wax’ in P.T. Nicholson and I. Shaw (eds.) 2000. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge.

Raven, M.J. 1988. ‘Magic and Symbolic Aspects of Certain Materials in Ancient Egypt’, Varia Aegyptiaca 4, 237-242.

Raven, M.J. 2012. Egyptian Magic: The Quest for Thoth’s Book of Secrets. Cairo.

Teeter, E. 2011. Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge.

[/expand]