Balabish

Rediscovering an Expedition

Carl Graves

Balabish was the location of a large regional cemetery serving a vibrant local community in Egypt from the Second Intermediate Period to the New Kingdom (1650-1295 BC). Being a mostly flat area of ground on the desert edge east of the modern town of El-Balabish, roughly 20km from the ancient necropolis of Abydos, the site today reveals little of its past significance.

|

|

A regional cemetery

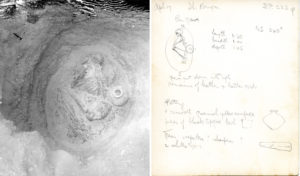

The cemetery of Balabish was excavated in 1915 on behalf of the American Branch of the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF) under the direction of Gerald Averay Wainwright (1879-1964). The cemetery was split into two parts, those burial pits along the cultivation edge and those lying further back in the desert area. This division reflected two differing burial customs, the first of a Second Intermediate Period Pan-grave community and the latter of the local Egyptian New Kingdom, though there was little definition between the two areas of burials.[1]

A Pan-grave community at Balabish

Though developments in burial position and tomb structure in Pan-grave culture are recently being reassessed, the material culture is distinct across all cemeteries.[2] Pan-grave burials are typified by the presence of leatherwork, shell, weapons, and animal skulls – all of which appear regularly in the archives of the excavation now kept in the Egypt Exploration Society’s Lucy Gura Archive (the Pan-grave culture was initially discovered during W M F Petrie’s excavations on behalf of the EEF at Diospolis Parva in 1898-99). As well as these burial goods, a distinctive ceramic type is also found. All Pan-grave manufactured vessels are of an open form, usually with a burnished red surface and blackened rim, marked by a defined rim. The interior of the vessels are usually black, as can be seen on the two sherds shown here.

|

|

Based on similarities in material culture, it is likely that the Pan-grave people originated south of Egypt, probably related to the cultures of Nubia.[3] During the decentralisation of the Egyptian state during the Second Intermediate Period (1650-1550 BC), these communities travelled north, into the Nile valley and settled predominantly in Upper and Middle Egypt. Research on the spread of Pan-grave cemeteries and the contents of their burials indicate that they were probably employed by Egyptian officials, perhaps in a military or security role. Closed vessels of Egyptian manufacture imply that they were being supplied by Egyptians, and the presence of Pan-grave communities in Middle Egypt along the probable border between the Theban rulers in the south and the Hyksos rulers in the north may indicate that they were positioned to maintain this area.[4] Their allegiance to the Theban rulers may have helped Kamose and Ahmose to reunify Egypt at the end of the Seventeenth Dynasty.

Egyptian burials at Balabish

Out of the 242 recorded burials uncovered at Balabish, 181 were of a typical Egyptian type and datable to the Eighteenth Dynasty. The discoveries made in these later burials indicate that Balabish was the necropolis for a varied local community at the centre of a complex trade network. Ceramics in the tombs, which were usually simple pit burials with no preserved superstructures, included specimens manufactured across the eastern Mediterranean.[5]

|

|

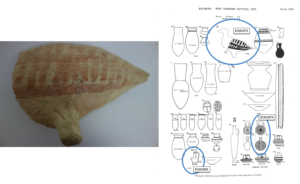

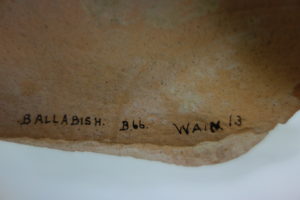

As well as elaborate foreign wares, the cemetery included an array of locally produced Egyptian ceramics. ECM 1973 is an example of a bird-shaped vessel that was found in burial 66 at Balabish. Plate 25 from the site publication includes a line-drawing of the vessel as it may once have appeared.

The story of objects

As well as informing researchers about the history of a tumultuous period of ancient Egyptian history, Balabish also provides an example of how archives, objects, and publications can be used together in order to reconstruct an expedition to a site. Reanalysing excavation and distribution records is crucial for understanding artefacts and sites in their original contexts and is the subject of a recent project, Artefacts of Excavation (http://egyptartefacts.griffith.ox.ac.uk/).

|

By rediscovering the objects now kept in the Eton Myers Collection in the archives of the Egypt Exploration Society it is possible to affirm their original provenance as well as the tomb groups to which they belong. Wainwright probably kept many of these ceramics in his own collection as examples and for teaching, as evidenced by a unique numbering system written onto the artefacts (in the format WAIN.XX). These items were then donated to Eton College by Wainwright himself in 1959.

Objects made their ways into collections in a variety of ways, sometimes directly through division from excavations, auction or market sales, through third-party distribution, via donations, or illicit digging. Provenance is difficult to confirm in many of these scenarios and therefore archival and published records are essential for bridging this gap in order to tell the full story of the artefact from its ancient past through to its more recent history.

[expand title=”Endnotes”]

[1] Wainwright 1920: 2

[2] De Souza 2013

[3] Edwards 2004: 99-101

[4] Bourriau 1999: 46-47

[5] for further information see Gallorini 2012

[/expand]

[expand title=”Bibliography and Further Reading”]

Artefacts of Excavation: http://egyptartefacts.griffith.ox.ac.uk/

Bourriau, J. 1999. ‘Some archaeological notes on the Kamose texts’, in Leahy, A. and J. Tait (eds), Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honour of H S Smith. London, 43-48.

De Souza, A. 2013. ‘The Egyptianisation of the Pan-grave culture: A new look at an old idea’, The Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology 24, 109-126.

Available via www.acadedmia.edu : http://www.academia.edu/4266639/The_Egyptianisation_of_the_Pan-Grave_Culture_A_New_Look_at_an_Old_Idea

Edwards, D. N. 2004. The Nubian Past: An archaeology of the Sudan. London and New York: Routledge.

Gallorini, C. 2012. ‘Innovation through Interactions: A Tale of Three ‘Pilgrim Flasks’’, in C. Graves and S. Gregory (eds.), Connections: Communication in Ancient Egypt, University of Birmingham http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/connections/Essays/CGallorini.aspx

Gallorini, C. 2016. ‘”Would I lie to you?” The truth behind object marks and museum catalogue entries’, in S. Boonstra (ed.), Objects Come to Life, Birmingham Egyptology

https://more.bham.ac.uk/birminghamegyptology/virtual-museum/objects-come-to-life/object-marks-and-catalogue-entries/

The Egypt Exploration Society: www.ees.ac.uk

The EES Lucy Gura Archive Balabish tomb cards: https://www.flickr.com/photos/egyptexplorationsociety/albums/72157658090111365

The EES Lucy Gura Archive Balabish negatives:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/egyptexplorationsociety/albums/72157658064490886

The EES Lucy Gura Archive Diospolis Parva negatives:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/egyptexplorationsociety/albums/72157663651388046

Petrie, W. M. F. 1901. Diospolis Parva: The cemeteries of Abadiyeh and Hu 1898-99. London: The Egypt Exploration Fund.

Available online: https://archive.org/details/diospolisparvac00macegoog

Wainwright, G. A. 1920. Balabish. London: The Egypt Exploration Society.

Available online: https://archive.org/details/balabish37wain

[/expand]