In Search of the Essence of Place

Petr Král. First published as ‘Enquête sur des lieux’ (Flammarion, 2007); translated by Christopher Moncrieff (Pushkin Press, 2012)

Recommended by Jon Stevens

Petr Král was a Czech writer, who died in 2020. ‘In Search of the Essence of Place’ was one of his last books, published in 2007. Král was born in German occupied Prague and grew up under Communism. After the ‘Prague Spring’, like many writers and intellectuals, he fled to Paris where he spent the next thirty years, apart from a short period in North America. He returned to Prague in 2006.

‘In Search of the Essence of Place’ is an elliptical and fragmented journey through Král’s life. It is a tale of exile and of displacement, in which primacy is given to the places he experienced rather than the people he met. Král was a member of the Czech surrealist movement and, on his first visit to Paris, he wanders the streets searching for the home of André Breton (who he refers to obliquely as ‘the prophet’). Following the example of Breton’s autofiction Nadja, Král’s text is interspersed with commonplace black and white photographs; and like Breton he is preoccupied by the ‘strangeness of things and places’.

The most unsettling aspect of places is their lack of clear boundaries…even their frontiers are hidden from our eyes by their deceptive drifting motion…(as in) the distinctive way in which the decoration of the most ornate palaces breathes in and out…and then suddenly ceases, when we study it too closely, leaving us with an inanimate lump of masonry.

Unlike Gertrude Jekyll’s numerous other “garden books”, which are predominately dedicated to the planning and maintenance of a garden over the year, Old West Surrey was intended to memorialise the elements of rural working-class life that she saw rapidly disappearing from her beloved late nineteenth-century stomping-grounds. Roving from the architectural features of specific properties to characters remembered from childhood church sermons, fragments of dialect, dress, custom, and house ornament; and peppered with her own photographs and illustrations, Jekyll’s text is devoted to recording her impressions of local culture, used to promote her own Arts and Crafts sensitivity to place. This work is an important example of the twentieth-century reclamation of the distinctiveness of local village life, and Jekyll’s prime concern is the countryside included in her personal definition of Old West Surrey.

Unlike Gertrude Jekyll’s numerous other “garden books”, which are predominately dedicated to the planning and maintenance of a garden over the year, Old West Surrey was intended to memorialise the elements of rural working-class life that she saw rapidly disappearing from her beloved late nineteenth-century stomping-grounds. Roving from the architectural features of specific properties to characters remembered from childhood church sermons, fragments of dialect, dress, custom, and house ornament; and peppered with her own photographs and illustrations, Jekyll’s text is devoted to recording her impressions of local culture, used to promote her own Arts and Crafts sensitivity to place. This work is an important example of the twentieth-century reclamation of the distinctiveness of local village life, and Jekyll’s prime concern is the countryside included in her personal definition of Old West Surrey.

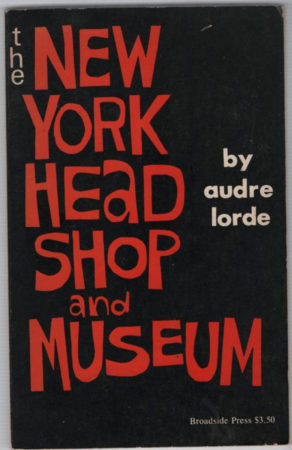

Sara Ahmed observes that Lorde’s writing is ‘personal testimony as well as political speech’ and that she ‘made life itself a political art, an art which you must craft from the resources that you have available’. One of her most crucial resources was New York, the place where she was born and where she lived for significant periods of time. Her 1975 collection New York Head Shop and Museum (now out of print but available as part of her Collected Poems), is both a portrait of the city as it slid into dereliction in the 1970s and a metaphorical act of taking to the streets in order to reclaim space and assert the existence of the marginalised. A glance at the contents list indicates the extent of New York’s critical role in the collection –titles include ‘New York City 1970’, ‘To Desi as Joe as Smoky the Lover of 115th Street’, ‘A Sewerplant Grows in Harlem’, ‘A Birthday Memorial to Seventh Street’, ‘A Year to Life on the Grand Central Shuttle’, ‘A Trip on the Staten Island Ferry’ and ‘Memorial III from a Phone Booth on Broadway’. The poems themselves are filled with references to a wide range of identifiable places all over New York, including the subway, the Staten Island Ferry, East Side Drive, Wall Street, Fourteenth Street, Riverside Drive, Brighton Beach Brooklyn and 125th Street and Lenox. The city that emerges from New York Head Shop is overwhelmingly deficient but richly lived, containing occurrences of horror, heartbreak and sometimes happiness.

Sara Ahmed observes that Lorde’s writing is ‘personal testimony as well as political speech’ and that she ‘made life itself a political art, an art which you must craft from the resources that you have available’. One of her most crucial resources was New York, the place where she was born and where she lived for significant periods of time. Her 1975 collection New York Head Shop and Museum (now out of print but available as part of her Collected Poems), is both a portrait of the city as it slid into dereliction in the 1970s and a metaphorical act of taking to the streets in order to reclaim space and assert the existence of the marginalised. A glance at the contents list indicates the extent of New York’s critical role in the collection –titles include ‘New York City 1970’, ‘To Desi as Joe as Smoky the Lover of 115th Street’, ‘A Sewerplant Grows in Harlem’, ‘A Birthday Memorial to Seventh Street’, ‘A Year to Life on the Grand Central Shuttle’, ‘A Trip on the Staten Island Ferry’ and ‘Memorial III from a Phone Booth on Broadway’. The poems themselves are filled with references to a wide range of identifiable places all over New York, including the subway, the Staten Island Ferry, East Side Drive, Wall Street, Fourteenth Street, Riverside Drive, Brighton Beach Brooklyn and 125th Street and Lenox. The city that emerges from New York Head Shop is overwhelmingly deficient but richly lived, containing occurrences of horror, heartbreak and sometimes happiness.

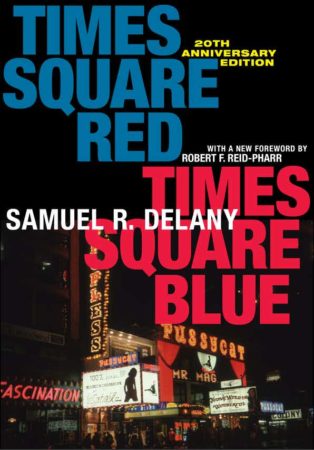

Times Square Red, Times Square Blue provocatively explores the redevelopment of New York City’s 42nd Street, or the Deuce, since the start of the 1960s – ‘a violent reconfiguration’ of the landscape of the city. The book consists of two extended essays, each moving ‘along different trajectories and at different intensities … two attempts by a single navigator to describe what the temporal coastline and the lay of the land looked like and felt like and the thoughts he had while observing them’. Delany playfully but instructively tracks the shift of one of the world’s most famous urban places – Times Square – from a locale hinging on pornography and public sex to one structured around tourism, ‘family values and safety’. In evoking and mourning the disappearance of the old Times Square, Delany illuminates the complex social relationships that developed there and were subsequently lost, exploring the pleasure and importance of communication across classes and in public spaces, and the crucial differences between institutionally-engineered networking (which tends to take place indoors) and contact, which is associated with public space and is more broadly social and random.

Times Square Red, Times Square Blue provocatively explores the redevelopment of New York City’s 42nd Street, or the Deuce, since the start of the 1960s – ‘a violent reconfiguration’ of the landscape of the city. The book consists of two extended essays, each moving ‘along different trajectories and at different intensities … two attempts by a single navigator to describe what the temporal coastline and the lay of the land looked like and felt like and the thoughts he had while observing them’. Delany playfully but instructively tracks the shift of one of the world’s most famous urban places – Times Square – from a locale hinging on pornography and public sex to one structured around tourism, ‘family values and safety’. In evoking and mourning the disappearance of the old Times Square, Delany illuminates the complex social relationships that developed there and were subsequently lost, exploring the pleasure and importance of communication across classes and in public spaces, and the crucial differences between institutionally-engineered networking (which tends to take place indoors) and contact, which is associated with public space and is more broadly social and random.

This is a queer book – one that refuses the well-worn and instantly recognizable structure of academic books, that doesn’t follow the storyline academic books are supposed to follow. As Schulman writes in her introduction, ‘some ideas have to be formally replicated, instead of being described. They have to be evoked.’ The Gentrification of the Mind is a memoir and analysis of the years during the AIDS crisis during which Schulman witnessed the disappearance of the New York she knew and loved, with the spectre of AIDS moving hand-in-hand with gentrification and mainstream consumerism. It laments lost places and lost people (‘destroyed neighborhoods remain destroyed’) but it is also a celebration of difference and futurity, of using activism and the arts to reclaim those lost places: ‘in order for radical queer culture to thrive, there must be diverse, dynamic cities in which we can hide/flaunt/learn/influence – in which there is room for variation and discovery’.

This is a queer book – one that refuses the well-worn and instantly recognizable structure of academic books, that doesn’t follow the storyline academic books are supposed to follow. As Schulman writes in her introduction, ‘some ideas have to be formally replicated, instead of being described. They have to be evoked.’ The Gentrification of the Mind is a memoir and analysis of the years during the AIDS crisis during which Schulman witnessed the disappearance of the New York she knew and loved, with the spectre of AIDS moving hand-in-hand with gentrification and mainstream consumerism. It laments lost places and lost people (‘destroyed neighborhoods remain destroyed’) but it is also a celebration of difference and futurity, of using activism and the arts to reclaim those lost places: ‘in order for radical queer culture to thrive, there must be diverse, dynamic cities in which we can hide/flaunt/learn/influence – in which there is room for variation and discovery’.

This book provides a useful way to conceptualise the differing scales of British and American landscapes in the context of nature writing from the nineteenth century to the twentieth century. Hooker suggests that many British writers demonstrate ‘ditch vision’ in their portrayals of environments. Rather than grand expanses, this approach studies microcosms of the wild in landscapes otherwise deemed increasingly urban. Hooker takes his lead from Richard Jefferies who in ‘The Pageant of Summer’ finds a ditch overflowing with ‘Green rushes, long and thick … the white pollen of early grasses … hawthorn boughs … briars … buds’ ([1884] 2011: 41–2). The observation leads him to remark, ‘So much greater is this green and common rush than all the Alps’ (ibid.: 43). Hooker applies his concept of ‘ditch vision’ to writers including Edward Thomas, John Cowper Powys and Frances Bellerby.

This book provides a useful way to conceptualise the differing scales of British and American landscapes in the context of nature writing from the nineteenth century to the twentieth century. Hooker suggests that many British writers demonstrate ‘ditch vision’ in their portrayals of environments. Rather than grand expanses, this approach studies microcosms of the wild in landscapes otherwise deemed increasingly urban. Hooker takes his lead from Richard Jefferies who in ‘The Pageant of Summer’ finds a ditch overflowing with ‘Green rushes, long and thick … the white pollen of early grasses … hawthorn boughs … briars … buds’ ([1884] 2011: 41–2). The observation leads him to remark, ‘So much greater is this green and common rush than all the Alps’ (ibid.: 43). Hooker applies his concept of ‘ditch vision’ to writers including Edward Thomas, John Cowper Powys and Frances Bellerby.