By Hannah Christopher (BA English Literature, University of Birmingham)

I am surprised to have woken up in the dark. In my mind, September feels like it should be clutching onto summer more than it has. My weather app informs me that the sun will rise whilst I am underground, screeching through the rabbit warren of tunnels that link London Bridge to Euston. Although I never usually rise with the sun, I want to see it this time and the thought of missing its first appearance is disappointing.

It is 6am but the tube is far from empty. Next to me there is a traveller with matching coral suitcases and opposite me a commuter with hair still swirled upwards by recent contact with a pillow. To my right, four lads are shouting and laughing at alarm clock volume, their drunk conversation is surreal and cyclical, sips of phrases pass between them, echoed and repeated. Some of us have slept, others will soon shut the curtains on the sunlight and sleep through the day. For now, we shuttle under the dark city together. I think about how strange the tube is, necessity or desire has united us to this mobile waiting room before we are called out to our real destinations. I think about trains, the infrastructure which supports these tunnels and our dependence on these technologies, mechanical and digital, which enable us to live between places, ignoring nature’s rhythms: long distances are contracted by transport, night and day blurred by electric light, hot and cold levelled by air conditioning, the internet dividing friends between embodied and online experiences. As I emerge from the tube station and turn into the rail station, I am strangely relieved that it was a cloudy sunrise, I feel I have missed nothing. I face away from the dawn and take a picture of the glowing underground sign instead.

Sunrise at Euston Station

My destination is the International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester for the WomenTalkPlace symposium Talking Place. There are five panels throughout the day, aiming to facilitate conversations between contemporary place writers. The panels on place memoirs, novels, writing about places as magical experiences, and writing politically through landscape consider different writers’ methods and reasons for engaging with places in literary ways. Throughout the day, what came across most strongly, is that there are many ways to exist in a place; no approach to place is quite the same and many approaches combine seemingly opposite narratives of natural and digital, past and present, personal and geological, fiction and non-fiction.

Liptrot’s memoir responds to the complexity of navigating a digital and natural world simultaneously

In the first panel Amy Liptrot read from her Berlin memoir, The Instant. The chapter documents how she embarks on a series of excursions to traffic islands around Berlin with a new lover. The chapter drifts between romantic anecdotes of hands held and emails exchanged, before washing up on these traffic islands every so often; each island has a ‘mission report’, narrated like a Springwatch segment. The digital journey threads through the natural, a theme which runs throughout the book. Liptrot names the chapters after extended metaphors, many of them synthesising the technological and the natural: ‘a google maps tour of the heart’, ‘traffic islands’, ‘digital archaeology’. Liptrot’s memoir responds to the complexity of navigating a digital and natural world simultaneously which is reflected in the way that she writes.

Later, in a panel discussing magic and connections, Jeff Young’s reading from Ghost Town took us through the streets of Liverpool, unlocking stories from the city’s past by exploring the marks on the landscape that stories have left behind. Young describes the visibility of the past in a present landscape, making this vibrant city simultaneously a kind of Ghost Town. His memoir combines layers of civic history as well as his own story; in doing so, he writes himself into this landscape. He receives emails from readers who identify with his story, saying things like ‘you have written my childhood’. There is a continual repositioning of whose story is the story of this aggregate place which spans both distance and time.

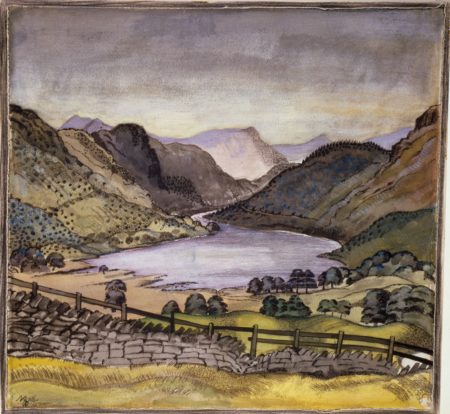

Another memoir writer, Nicola Chester, discussed her new book On Gallows Down as part of a panel about ‘belonging’. Chester’s book claims to be a ‘story of a life shaped by landscape’, yet as she spoke about her life, which she describes as being able to see ‘laid out’ in their chapters from atop a local hill, I felt that she was instead giving us a landscape shaped by her life. Chester’s narrativization of her personal life interwoven with the topography of West Berkshire goes on to shape our perceptions of this place, even as her life was shaped by the landscape initially. The individual and the landscape become synthesised and invite the reader into an active dialogue with place.

Throughout the day, there were a number of questions raised concerning the struggle of separating fiction and non-fiction in place writing. In the first panel, Amy Liptrot, Anna Fleming and Lily Dunn acknowledged, as non-fiction writers, that ‘memoir can slip precariously into fiction’. Later, Fleming addressed this indirectly as she spoke about the distance between herself and her work. Fleming used an illustration from Melissa Febos’ Body Work which describes memoir writing, not as an egotistical project, but as a process in which the self is made transparent for other people to inhabit. The self becomes detached from the work, simply a skin through which a reader can see the world from a different perspective, or an unfamiliar landscape with clarity. This distancing process steps onto the slippery slope between non-fiction and fiction. I also feel this tension as I write this blog post, emphasising some things and not others in an attempt to curate this day into a sort-of conclusive story, a kind of fiction itself. Yet, on the flip side, fiction writer Fiona Mozley, noted how her books were a kind of non-fiction, reflecting places and experiences in her life. She noted a similar feeling of vulnerable exposure that Liptrot felt in publishing her intimate memoir, The Instant. The relationship between writer, place and story is entangled, creating unique works which sit along a spectrum between fiction and non-fiction.

The relationship between writer, place and story is entangled, creating unique works which sit along a spectrum between fiction and non-fiction.

It was between the last two panels when I noticed a jazzed up literary notice by the door, ‘sleep and waking are two opposed kingdoms. Please be considerate and keep noise to a minimum.’ Perhaps this statement was true when night meant sleep and darkness and the waking kingdom was built anew each day with the dawn chorus, but our nights, more and more, take on their own luminosity and night life.

I thought back to the tube this morning and my shared journey joined with my unlikely travel companions, and the blurring of waking and sleeping kingdoms under artificial light — not opposing but operating simultaneously. As if sitting between kingdoms, like the crossed paths of unlikely travellers, the way writers complement landscape with digital spaces, overlay the past with the present, combine internal emotional life with geographical topography, and blend fiction with non-fiction in ways that are not oppositional but complementary, seems to speak into this current moment. Many of these writers’ responses to place are grounded in the natural place, the urban place, the digital place, the historic place etc., sometimes weaving a narrative from all of these at the same time, giving a richer and deepening experience of what it means to exist in a place in our time.

Sunset at Manchester Piccadilly Station