I remember feeling very eccentric in GCSE English lessons when friends complained about all the descriptions in Far From the Madding Crowd and wanted to skip ahead to the plot. The descriptions were the plot I thought. I was hazy about the order of human events, but the fern-grown hollow, the dangerous clover field, the ridge against the sky on which an occasional small figure would appear moving steadily on an unknown journey – all this was more real to me than the room I sat in. I was learning to read rooms as well though, and not only those ancient and easily romanticised ones I already cared about but bungalow paradises, city hotels, and the portacabin next to the astro-turf where those first encounters with life-changing literature unfolded. Twenty-five years later I’m very glad to help bring together, in the Arts of Place network, a wealth of people who are thinking in careful, imaginative, informed and questioning ways about our surroundings.

Much of my research over the years has been concerned with the presence of the past, and especially the past as it appears in landscapes and buildings. I’m interested in reading as a form of conversation across time and space, and in the capacity of art to establish complex relationships with history’s voices, variously reviving and revising them. My first book Romantic Moderns (Thames & Hudson 2010; Guardian First Book Award, Somerset Maugham Award) argued that some of the most original work of the modernist period emerged not from wholesale rejection of inherited ideas and places, but in finding new forms that might stretch to include valued histories and new possibilities.

In Weatherland: Writers and Artists under English Skies (Thames & Hudson 2015; shortlisted for the Ondaatje Prize and adapted in 10 parts for Radio 4), I wrote a version of English literary history told in terms of the different weathers that have preoccupied writers and indeed whole cultural milieus at certain times. The book is in part an elegy for a climate we won’t know again, but more than that, and more importantly at the present time, it addresses the power and complexity of weather as it is experienced, as it is imagined, and as it is shaped by the arts.

For the past several years I’ve been working on a different kind of place-related project, one which has propelled me into a great deal of new thinking and learning. In The Rising Down, to be published by Faber, I concentrate on a few square miles of West Sussex, and investigate what this place has looked like to people over time. The method of close geographical focus has meant that, as I think my way through history, I don’t reach for the famed and canonical but try to work from the ground up: who was here? It’s made me appreciate the extraordinary and sometimes underestimated research done by local historians, and the new perspectives that emerge when we forge connections between international and local thinking.

Many of my essays and reviews can be accessed from links on my website: www.alexandraharris.co.uk

Examples of my work on place

“Above all this is a book about art and place. Its protagonists are always out looking at England and they invite us to follow in their tracks … They were taking possession of the particular and local. And, like Chaucer, they were collecting stories along the way.”

“So, by reading, I have tried to watch people watching the sky – and people feeling the cold and getting wet, and shielding their eyes from the sun. Virginia Woolf talked about biographers hanging up mirrors in odd corners to reflect their subjects in unexpected ways. I have tried to hang a mirror in the sky, and to watch the writers and artists who appear in it.

“I’m still imagining calendars: figures of the modern ‘labours of the months’ painted in blue on delft tiles, marks on a bedroom wall that tell the date from the moving square of light coming in at the window…”

I worked with the arts and environment charity Common Ground, the publisher Little Toller, and contemporary artists to make a small book called Time and Place, published by Little Toller in 2019. This connects with a longer-term project of mine on the culture of the calendar, the seasons and the marking of time. I’m interested in all kinds of art that has played a role in creating days and months with character and association, making comprehensible shapes within the stream of time. Time and Place asks how time moves in particular localities. My text looks back at the history of local or site-specific calendars, and considers the many material forms they have taken.

Together, the University of Birmingham and Common Ground commissioned new calendrical work. Among the artists is the photographer Jem Southam. He traces intersections of cosmic, human, and bird time as he watches, night after night, year after year at a bend of the River Exe, becoming so deeply part of the place and its ecology that he can see patterns that might be invisible to others.

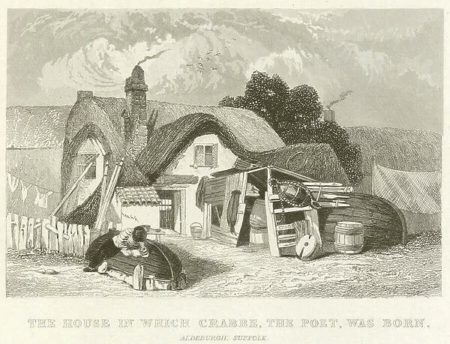

My essay ‘The Marsh and the Visitor’ is about going home to the area of Sussex in which I grew up and realising how little I knew about it. It’s about the common quandary of being deeply attached to rural places while not belonging in them. It was the starting point for a concerted and sometimes overwhelming effort to learn some of the languages of the place and to bring to it something of my own.

“Item four pigs, item fourteen quarters of barley, item one dozen of napkins, item goods in the milkhouse: outside and inside, room by room, the items of lives are spelled out. In a great many cases this is the fullest account to survive of an individual’s existence. An account, literally: added up at the end.”

A commission from the superb Museum of English Rural Life in Reading prompted me to think about the objects listed in rural inventories. My response was published on the Caught by the River website, where you can also read poems by Melissa Harrison, commissioned for the same project.