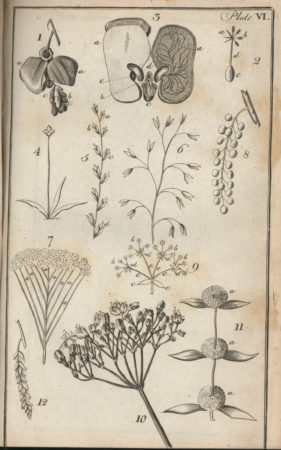

‘Seeds, to our eye invisible’:

The Botany Beneath George Crabbe’s Poetry

with guest speaker Dr James Bainbridge (Liverpool)

Monday 22 January, with Jessica Fay in response and conversation.

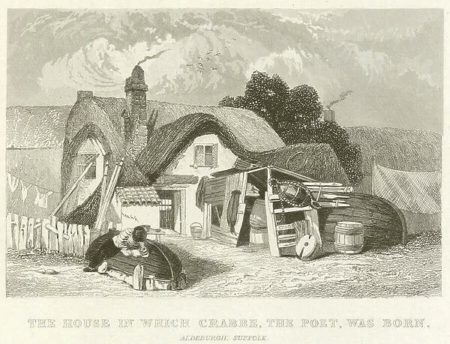

Botany was a key interest of the poet George Crabbe. “Give me a wild, wide Fen, in a foggy day,” he wrote, “and every botanist [is] an Adam who explores and names the creatures he meets with.” Between the publication of The Newspaper in 1785 and the 1807 Poems, much of his writing focused on the production of new botanical works. But this was a period of great change for English botany, and whilst Crabbe made use of competing Systems to arrange the natural world as he observed it, he was also drawn to the disorderly fringes of the science – things that were difficult to classify.

In January 2024, James Bainbridge joined us to examine the ways botany shaped Crabbe’s poetry, from the minuteness of detail in his description, to the study of distinction between individual subjects. James is a Lecturer in English at the University of Liverpool. He teaches and researches in eighteenth and twentieth-century literature with a particular interest in the influence of theology and natural sciences on the literature of the long-eighteenth century. He is currently writing a biography of the poet A.S.J. Tessimond and publishes regularly on Crabbe.

Watch the recording of this talk below and read on for some highlights.

Why do so few people read Crabbe today? By way of introduction, James explained why this is not a new question. Though he counted Thomas Hardy, Jane Austen, Walter Scott, Ivan Turgunev, Leo Tolstoy, George Eliot and Elizabeth Gaskell amongst his admirers, Crabb quickly fell out of favour in the 19th century:

“What the novel does in the nineteenth century takes its seeds in what Crabbe is doing in poetry, and partly because he was writing in poetry, he quickly went out of fashion”

Against, Virginia Woolf’s alignment of Crabbe with weeds, James suggested that

“On the whole, Crabbe tends to describe the mallow and the bugloss, not because he thinks of them as weeds, but rather because he thinks of them as native species. That word native is used extensively in his writing to think about place, to think about people, to think about plants. These plants aren’t described by their not belonging, but rather the reverse. Crabbe is drawn to them because they belong to the specific places he describes.”

Discussing The Borough (1810), James presented an astonishing case for how Crabbe deployed a taxonomical arrangement to articulate similarities and differences, order and disorder, amongst his characters, places, and environments:

“The emphasis on locality in these works indicates an almost proto-ecological interest in nature which appears even more prominent in a work he proposed to write on trefoils. In this he declared an ambition to give ‘a narration of the progressive Vegetation of the spot it grows on, etc. etc. etc’; the emphasis clearly placed on the way that habitats change through successions of plant life.”

James ultimately argued that in The Borough

“Crabbe show the relationship between botany and place. There is offered a particular bed that fits the seed. He considers how over time a place may change due to the succession of plants which dwell there. And it is this level of narrative which he felt was lacking from simple taxonomic arrangement, and why in both his botany and poetry he moved towards a more ecological approach. Crabbe botanical interests, far from being mere adornments to the poetry, are integral to his narrative and thematic development. His descriptions of plants and landscapes are not just backdrop but they are interwoven with the human stories that he tells.”