Explore the travels of objects at TIDEfest

For the last five years the TIDE Project has been exploring Renaissance travel, promoting transcultural education in schools, and revealing hidden wonders from archives around the world. Nandini Das and Lauren Working invite Arts of Place friends to join TIDEfest, a free online literary festival over the weekend 31 July-1 August.

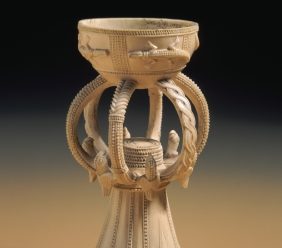

You can register here for a Creative Writing workshop 5.00-6.30pm on Saturday 31 July. Led by award-winning poets Sarah Howe and Fred D’Aguiar, the session will explore ideas of migration and cultural memory through objects that cross borders and spaces. A tobacco leaf leaves North American soil and ends up pressed between the pages of an Oxford botanical book; an ivory salt cellar carved by West African craftspeople leaves Sierra Leone for the courts of Europe. Using artefacts in Oxford museums and beyond, this workshop will encourage participants to think about the connections between objects and the imaginative places they take us.

Tobacco leaves travel to Europe… an ivory salt cellar sets out from Sierra Leone…

(Oxford, 2010)

(Oxford, 2010)

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by

Recommended by