By Andy Stafford

All you have to do is breathe

Samuel Beckett’s words in the play that premiered in 1969 would not probably have known of the near namesake in the Moroccan journal Souffles. But Beckett himself would have been acutely aware that the nature of souffles – breaths – is that they are to be repeated; and even if held in, they are prone, sooner – or later – to be blustered out. Souffles the 1960s journal then is indeed ‘protest in print’ and also an imprint of protest.

Gaol is not normally where poetry journals tend to land their editors, and Abdellatif Laâbi was unlucky enough to be running one during a state of emergency that was decreed in 1965 by Morocco’s authoritarian King Hassan II. Unlucky too that the crackdown (which ‘corrected’ a young Tahar Ben Jelloun) succeeded, by 1972, in only making the King paranoid of a coup or an uprising, and responsibility for which was easily attributed to Souffles. With its ardent desire for a new Moroccan literature and culture of the people, in the newly-independent nation free of France’s 40-year protectorate (but not the French language), Souffles literally breathed new life into Moroccan politics and intellectual debate between 1966 and 1972; not just in Rabat where it was published but across North Africa and the Atlantic – notably to Cuba, where Souffles dialogued with the Tricontentale journal. The artist Mohamed Melehi even incorporated Cuba’s slogans into the art-works that were reproduced in colour in Souffles. Indeed, like its radical Cuban counterpart, Souffles began an Arabic version in 1970, Anfas: ‘breath’ in Arabic indeed – but also spirit, soul, person, words…

When I started working on Souffles in 1998, on a journal already 30 years old, it was, I realise now, because it had managed to occupy, however briefly, a unique position in literary and post-colonial history. Marxist in orientation, Souffles was an anti-colonial, avant-garde, anti-folkloric, dual-language poetry journal that, however swiftly (6 years and less than twenty numbers), covered many if not all of the fundamental political and aesthetic questions of our age. And yet, as we look back at this radical stance and its importance for Moroccan, francophone and global literature and politics in the decades since, something has now, quite clearly, shifted.

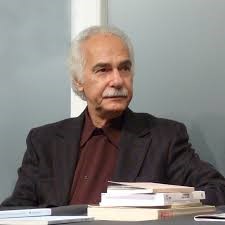

I remember interviewing the founder of Souffles, Abdellatif Laâbi, in Paris in 2007, and was struck not just by his understandable (but politically egregious and tactically disastrous) dismissal of Islamism as a political force, but also by the concomitant pessimism he felt towards the Arab world at the time. The collapse of Marxism-Leninism, of Baathism’s radical gestures, the containment of Palestinian protest and the catastrophe of the Bush-Blair war on terror, must have felt to Laâbi like a cruel reward for his eight long years during the 1980s languishing in the prisons of Hassan II, where he was tortured, lost many comrades, endured solitary confinement and even went on hunger strike. All that for running a poetry journal on a shoestring.

A deep breath: breathe in the air

If only Beckett was right: if breathing is all we have to do, then we have won; alas, what we really need to do instead is what a student of mine (he remains nameless but knows who he is) referred to in error as the journal Soufflés! A soufflé not only has space for hot air to be blown into it, it risks (by my cooking experience!) boiling over: let’s blow air – via literary study, university strike-action or climate militancy or any other radical activity – into the revolts around the Arab world (and elsewhere): victory to the Sudanese uprising, to the hirak in Algeria, to the movements in Iraq, Iran and Lebanon, to the strikes returning to Egypt: ‘the weapons of critique, wrote Marx, will never replace the critique by weapons’. We owe this blow of support, in particular, to the valiant people of Syria.

Then (the 1960s) and now: imperialism out of the Middle East!

The opinions expressed are those of the author.