A Starter Library on Populism

By PiAP’s Adrian Favero, Niko Hatakka, Judith Sijstermans, Mattia Zulianello – this piece originally appeared on EA Worldview

We asked each of the Research Fellows on the Populism in Action Project to give us opening recommendations to learn about populism, populist parties, and the future of European politics and society.

This is their Starter’s Library:

Dr. Adrian Favero, Switzerland focused Research Fellow

Nicole Loew and Thorsten Fass (2019) “Between Thin- and Host-ideologies: How Populist Attitudes Interact with Policy Preferences in Shaping Voting Behaviour,” Representation

Loew and Fass, from the Freie Universität Berlin, explores the demand side of left-wing and right-wing populism in Germany. They focus on voters for the Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany) and Die Linke (Left Party), applying the ideational approach to populism as a framework for their research.

The study considers the complex interaction between populist attitudes, policy preferences, and voter choice. Loew and Fass build an analysis derived from the literature on host ideologies, such as socialism and nationalism, that influence voting behavior.

In their conclusion, they outline convincingly that on the demand side of politics, populist attitudes and strong policy preferences lead to votes for populist parties on either the left or the right. Yet voters with moderate policy concerns and strong populist attitudes are still more likely to vote for populist parties because these attitudes substitute for policy preferences.

The article sheds light on a group of voters who are less driven by policy preferences than they are motivated by populism itself. If this is true across the nation, populist parties can rely on either policies or populist attitudes as a driver to increase their vote share.

Shelley Boulianne, Karolina Koc-Michalska, and Bruce Bimber (2020) “Right-Wing Populism, Social Media and Echo Chambers in Western Democracies”, New Media & Society

Boulianne, Koc-Michalska, and Bruce Bimber explore the effect of self-exposure to social media–based “echo chambers” on the rise of right-wing populism.

Based on a large-scale survey of 4500 respondents conducted in France, the UK, and the US, the authors assess citizens’ experiences of echo-chamber effects and support for populist parties. The novelty of this strand of research is the study’s comparative approach, which rules out country-specific explanations such as economics and immigration.

The study also assesses the polarizing effect of echo chambers and polarization’s link to left-wing or right-wing ideologies. The authors conclude that exposure to selective information in social media echo chambers does not predict support for right-wing parties as opposed to other parties. However, they find an echo chamber effect in the context of offline discussions with like-minded people, which is associated with support for right-wing populists.

The findings challenge the common assumption that digital echo chambers increase the propensity to endorse right-wing populism.

Laurent Bernhard and Hanspeter Kriesi (2019) “Populism in Election Times: A Comparative Analysis of 11 Countries in Western Europe”, West European Politics

Bernhard and Kriesi, through a content analysis of press releases in 11 countries in Western Europe, offers an interesting comparative analysis of the populist ideology expressed by parties during election campaigns.

They evaluate three types of appeals: people-centrism, anti-elitism, and demands for popular sovereignty. They not only look at populist parties from both the radical right and the radical left, but also at the division of issue dimensions, such as culture and economy, in northern and southern Europe. The article combines quantitative text analysis with qualitative examples, providing the reader with helpful illustrations of the national context.

The authors conclude that mainstream parties are less prone to rely on populist rhetoric. Intriguingly, this challenges the assumption that mainstream parties adjust to populist strategies exhibited by the far left and right. This description of gradual populism among “extreme parties” is important because it highlights the importance of nuanced classification.

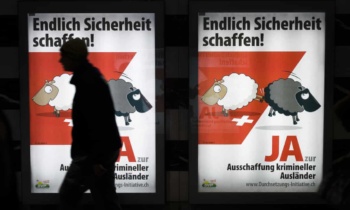

A Swiss People’s Party poster in 2016: “Finally Create Security” (Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images)

Dr. Niko Hatakka, Finland focused Research Fellow

Salla-Maaria Laaksonen, Mervi Pantti, and Gavan Titley (2020) “Broadcasting the Movement and Branding Political Microcelebrities: Finnish Anti-Immigration Video Practices on YouTube”, Journal of Communication

The authors analyze the usage of YouTube by Finnish anti-immigration movements after 2015.

Despite online platforms having significant effects on the style, contents, and form of populist radical right activism, in and parallel to the Finns Party, specific Finnish online movements have rarely been researched empirically. The study is based on qualitative content analysis of the actors, genres, functions, styles, framings, and strategies employed in YouTube videos affiliated to two separate movements, Rajat Kiinni and Suomen Kansa Ensin. The qualitative analysis is preceded and eloquently informed by a simple, yet effective, network analysis.

The paper highlights the role of microcelebrities as pivotal nodes in the movement’s network. Without explicitly stating the outcome, the authors display and discuss how YouTube’s properties and functions affect the process of empty signifiers uniting hybrid political movements.

Michael Hameleers and Rens Vliegenthart (2020) “The Rise of a Populist Zeitgeist? A Content Analysis of Populist Media Coverage in Newspapers Published between 1990 and 2017”, Journalism Studies

Hameleers and Vliegenhart’s article contributes to the discussion on the mainstreaming of populism as a thin-centered ideology in Western Europe.

Focusing on a 28-year period in the Netherlands, the authors use a dictionary-based approach to analyze the temporal prevalence of populist communication in newspapers. Measuring the number of articles which contain pre-selected words that are indicative of four selected elements of populist communication, the study portrays how people-centric and anti-elitist communication has become more prevalent over time.

The paper is the first attempt to use a word-based automated analysis of populist communication on a longer time scale. Because of its single country focus, it effectively proves an outlet-independent increase in the elements of populist communication measured.

Future studies seeking to pursue this method will have to resolve the problem of being able to use it reliably in a comparative setting. The difficulty of this task raises interesting questions about whether the thin-ideological understanding of the different elements of populism, for example viewing “the people” as the “ordinary people”, corresponds to the reality of how populist mobilizations are enabled by a staggeringly vast array of signifiers.

Jonathan Dean and Bice Maiguascha (2020) “Did Somebody Say Populism? Towards a Renewal and Reorientation of Populism Studies”, Journal of Political Ideologies

The mainstream of populism research is strongly rooted in the ideational approach, which regards populism as a set of ideas or a thin-centered ideology. So it is refreshing to read articles that engage with the “other” approach, the Laclaudian theory of populism.

Dean and Maiguascha critically analyze the strengths and weaknesses of both theoretical approaches and encourage populism scholars to critically evaluate whether their use of the concepts are useful. Specifically they urge scholars to ask whether their selected definition of populism can both feed into anti-populist rhetoric and provide momentum for “populist hype”.

The authors suggest that more scholarly attention should be directed to populism not as a concept but as a signifier that has potential to be more political than analytical, especially outside of academia. A good first step will be a more conscious effort by scholars to recognize and be transparent about the epistemic limits of our definitions and operationalization of “populist ideas”, “populist style”, and “populist logic”.

Referring to only one of these distinct elements comprehensively as “populism” makes little sense and enflames disputes between the different populism research communities. Further work to combine the theoretical aspects of the different sub-disciplines of populism research should be encouraged, and this article is an excellent contribution to such a pursuit.

Finns Party leader Jussi Halla-aho

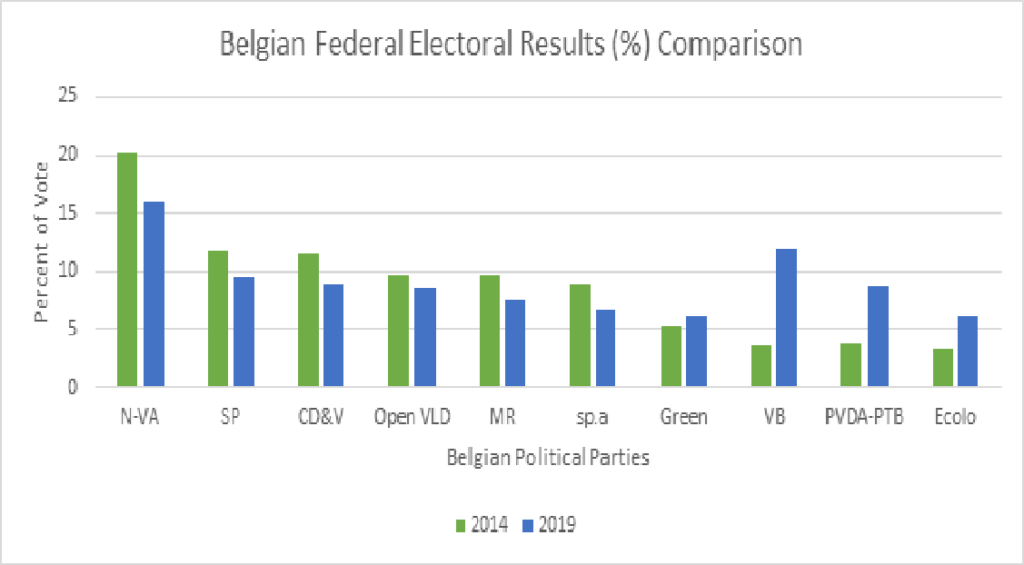

Dr. Judith Sijstermans, Belgium focused Research Fellow

Léonie de Jonge (2019). “The Populist Radical Right and the Media in the Benelux: Friend or Foe?”, The International Journal of Press/Politics

De Jonge’s work focuses on Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg and ties into the case of the Vlaams Belang (Flemish Interest, VB), one of four cases being studied by the Populism in Action Project.

Drawing on evocative interviews with media practitioners, de Jonge argues that the media in the Netherlands and Flanders have taken a more accommodating approach to right wing populist parties, in comparison with that of the media in Wallonia and Luxembourg. These approaches are shaped by mass media market dynamics in each country and the nature of their political systems.

De Jonge suggests that differing media responses have shaped the populist parties’ electoral trajectories. This speaks to an interesting dynamic within Belgium, where Flanders and Wallonia differ significantly in terms of populist radical right success. This has been further studied by Hilde Coffé.

It may seem incongruous to include a work so focused on the media in this review. However, in my early interviews with VB representatives, the media has been a pressing issue. The party seeks out support on social media to bypass what they see as a widespread “cordon mediatique” in the Belgian press. De Jonge discusses her work in a podcast (in Dutch).

Menno Fenger (2018). “The Social Policy Agendas of Populist Radical Right Parties in Comparative Perspective”, Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy

It is a stretch to say, as Fenger does, that “there has been only limited research on the attitudes of these populist radical right parties towards the welfare state”. However, the novelty in this article’s approach is its broad empirical comparison between six populist radical right parties.

The inclusion of Donald Trump as a populist radical right figure is controversial but interesting. Fenger shows a clear gap between the social policies portrayed by Trump and those of his European counterparts, despite “some European leaders highlight[ing] their association with the Trump Administration”. The strategy of adopting Trump’s language has emerged in the Flemish Interest, making it useful to include Trump here, if only to highlight how few substantive similarities exist despite the professed symbolic links.

The article raises more questions than it answers providing a starting point for further research. Why are some parties, as Fenger says, “dogmatic” whilst others are “pragmatic”? Should we include Trump in future analyses? What causes similarities in Dutch and Flemish approaches to social policy? Studies of PRRPs rarely cover such broad ground, and given the comparative aims of our own project, this article is a useful reference point.

Agnes Akkerman, Andrzej Zaslove, and Bram Spruyt (2017). “‘We the People’ or ‘We the Peoples’? A Comparison of Support for the Populist Radical Right and Populist Radical Left in the Netherlands”, Swiss Political Science Review

The authors of this article compare supporters of a populist radical right and populist radical left party in the Netherlands, the Partij voor de Vrijheid (Party for Freedom, PVV) and the Socialistische Partij (Socialist Party, SP) respectively. They test hypotheses on the attitudes that unite and divide these parties’ voters.

Populism in Activism Project co-investigator Stijn van Kessel has suggested that the SP has stepped away from its populist rhetoric. However, studying populism in parties on either side of the ideological spectrum is a useful way to move past preconceived notions about populism. The authors argue that, given their faith in the “people”, “a populist vote may not only be a vote against but also for something”. Both parties’ supporters hold populist attitudes and low levels of trust, but what supporters of each party are voting for differs.

Tying into Fenger’s discussions of social policy, the authors posit a certain symmetry in the welfare policies of PRR and PRL parties, hypothesizing that supporters of both support more social security benefits. However, their findings do not support this.

For those with an interest in this dynamic, other scholars have delved more deeply into the links between economic positions and populist attitudes in voters including in this article by Van Kessel and Steven Van Hauwaert.

Poster of Belgium’s Vlaams Belang party: “Thanks Voters!”

Dr. Mattia Zulianello, Italy focused Research Fellow

Lenka Buštíková and Petra Guasti (2019). “The State as a Firm: Understanding the Autocratic Roots of Technocratic Populism”, East European Politics and Societies

Buštíková and Guasti provide an excellent and intriguing analysis of technocratic populism, a little-studied manifestation of the populist phenomenon. Focusing on the case of Czech Republic since 1989, the authors ground a solid empirical analysis within a valuable theoretical framework, which greatly enhances our understanding of the many populist actors that do not fit the typical left-right categorization.

Technocratic populism is exemplified in the contemporary context by Andrej Babiš’ ANO 2011. This is the leading force in today’s Czech government, and “strategically uses the appeal of technocratic competence and weaponizes numbers to deliver a populist message”, which emerges “at critical junctures as an alternative to the ideology of liberal democratic pluralism”.

The authors argue that the broader appeal of technocratic populism in comparison with economic and nativist forms of populism, as well as its claim to rule in the name of “the people” on the grounds of technical expertise, make it a “sophisticated threat to liberal democracy”. In particular, by combining an emphasis on technocratic expertise with a people-centric message, this form of populism may lead to democratic backsliding by fueling civic apathy and by providing political actors with a master frame to “legitimize” concentrations of power.

Luigi Curini (2019). “The Spatial Determinants of the Prevalence of Anti-Elite Rhetoric Across Parties”, West European Politics

Spatial analyses of political competition are a true political science classic, and this article by Luigi Curini shows the utility and elegance of such approaches to the study of key aspects of contemporary party politics.

Using data from the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey data, the author conceptualizes anti-elitism “as a non-policy vote-winning strategy” that has “quasi-valence” features, because they can be positively evaluated by a wide pool of voters. In light of such properties, anti-elitism is understood as a strategy that can potentially be used by any political actor with the goal of increasing their electoral appeal.

Curini’s analysis suggests that the decision of political parties to focus on anti-elitism “does not depend entirely on some inner identity; it also depends on the spatial environment in which they compete”. Indeed, this paper reveals that a given party has a higher incentive to resort to anti-elitism if it is “ideologically ‘squeezed’ among adjacent parties”. Most notably, in such a context, focusing on anti-elitism may help a political party differentiate itself from its proximate competitors in the eyes of the electorate.

Sergiu Gherghina and Sorina Soare (2019). “Electoral Performance Beyond Leaders? The Organization of Populist Parties in Post-Communist Europe”, Party Politics

Gherghina and Sorina Soare offer an excellent example of how to study the impact of leadership and organizational features on the electoral performance of populist parties.

Grounded in the qualitative analysis of primary and secondary sources, the paper focuses on three cases from post-communist Europe that present considerable differences in terms of their electoral fate: the Bulgaria Without Censorship Party, the Party of Socialists from the Republic of Moldova, and the People’s Party-Dan Diaconescu of Romania.

Rather than treating leadership and organization as a single variable, as it is often the case in the literature, the authors operate a useful and meaningful distinction between the two in their analysis. This approach makes their contribution of interest to comparativists and to scholars of populism.

Most notably, the analysis reveals that personalization and concentration of power in the hands of charismatic leaders is not sufficient to achieve electoral survival. This paper highlights that endogenous factors are important in the decline of populist parties, especially if they do not develop proper organizational structures and rely instead on the personality of their leaders.