Mario Draghi’s governing bandwagon has been voted in. Expect a bumpy ride

By PiAP’s Principal Investigator Dr. Daniele Albertazzi and the University of Turin’s Dr. Davide Pellegrino. This post first appeared on The Loop, the EPRC’s Political Science Blog on 23/02/21.

On 13 January 2020, Matteo Renzi, leader of the personal, centrist party, Italia Viva (IV), withdrew his ministers from Giuseppe Conte’s second government. This triggered a government crisis that would end Conte’s time as Prime Minister.

Renzi was hoping to drive a wedge between the Democratic Party (PD) and its governing ally the Five Star Movement (M5S), restoring some visibility to his ailing party.

Though Renzi managed to get rid of Conte, he failed to give Italy a government that made a break with the past. Indeed, as the dust has settled, ‘government crisis’ has given way to yet more political continuity.

The usual suspects, sneaking in the back door

New PM Mario Draghi is a former head of the European Central Bank, with no previous direct involvement in politics. This clearly qualifies him as a technocrat. Yet his executive is staffed by many who are not just from the parties backing him, but appear to have been picked by them. Government positions have been gifted to the usual party insiders.

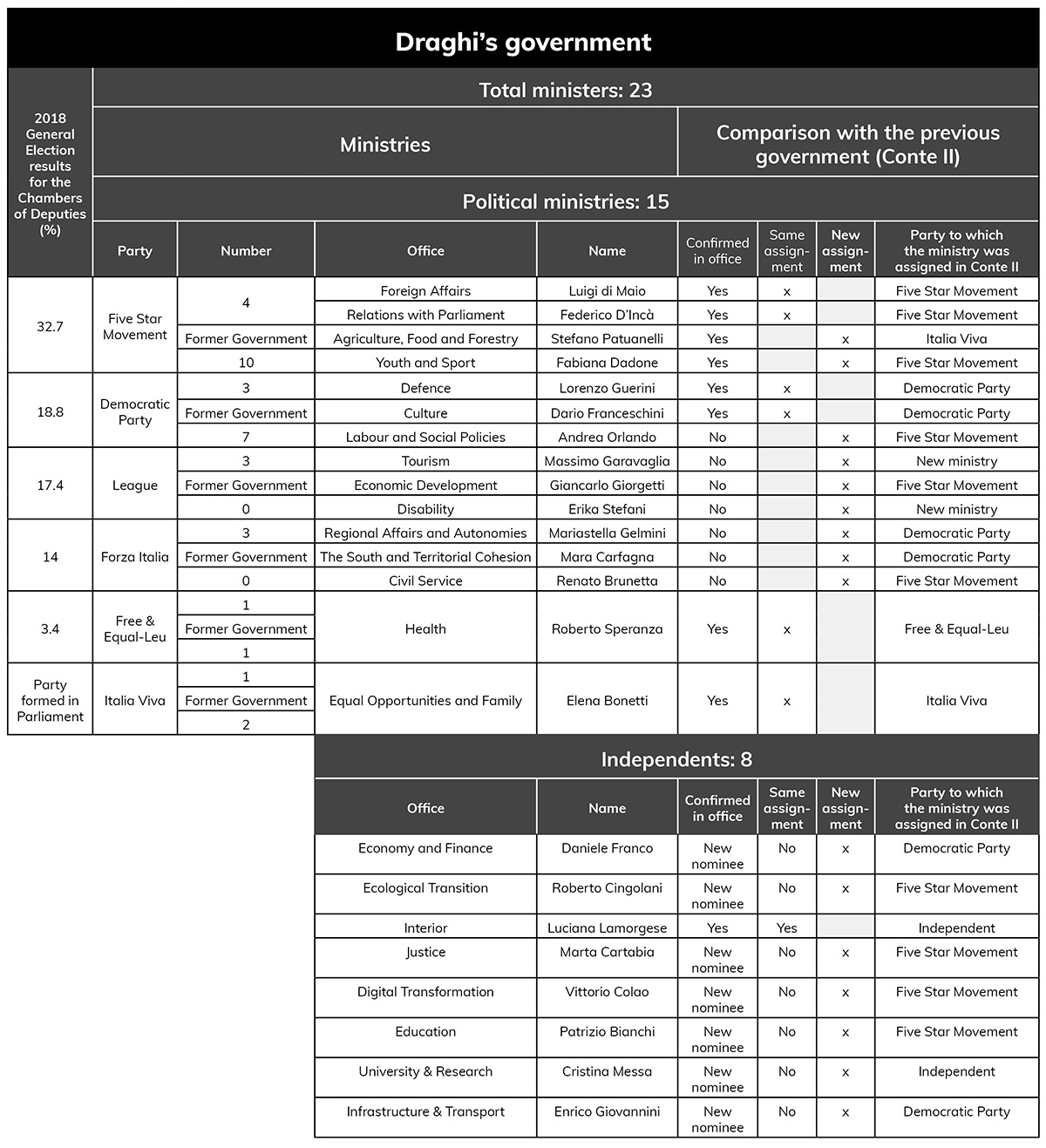

Draghi’s executive is staffed by as many as 15 political figures, alongside eight independents. This mirrors the size of the parliamentary groups that have jumped on his bandwagon. The executive is composed of five ministers from the M5S, and three each from the PD, League and Forza Italia. Parliamentary minnows gain one ministry each. See the table below.

Expelled by Renzi’s scheming, some of the usual suspects are taking revenge by sneaking in through the back door. Indeed, almost all ‘political’ ministers in the new government have already served in centre-left and centre-right governments. Several have been allowed to continue in the roles they held under Conte, while a few held ministerial positions years ago under Silvio Berlusconi.

Five Star Movement: anti-establishment no more

This has created an impossible situation for the populist M5S. It has received less than half the ministries it had controlled under the previous government, down from 10 to 4. Now, it must govern alongside ministers from Berlusconi’s hated governments.

Since the 2018 election, the M5S has reluctantly agreed to govern alongside almost all major Italian parties. Worse, it is now backing a former head of the European Central Bank as PM, having repeatedly rejected the idea that ‘technocrats’ be allowed to rule. This is hard to explain to the party’s grassroots. A considerable number of M5S MPs and senators refused to back Draghi’s government in Parliament. Its decision to back Draghi now may lead to a party split.

League: the elephant in the room

Unlike the M5S, the League won’t struggle to gain support from its members and electorate for backing Draghi. This is particularly the case now that the party controls the Ministry of Economic Development (see table). The League will enjoy a seat at the top table as the considerable amount of money coming from the EU via the Recovery Fund will be allocated to various projects. Unlike the M5S, the League’s problem is not ideological but all about competition within the right.

Brothers of Italy can feel smug about its consistent refusal to govern with the left, pointing to the League’s hypocrisy in cosying up to its former enemies

Giorgia Meloni, leader of the populist radical right party Brothers of Italy (FdI), will remain in opposition. She has an effective story to tell the electorate. According to the polls, she has been on an upward trajectory since 2019, much of it at the League’s expense. FdI will now feel smug about its consistent refusal to govern with the left. It can point to the League’s hypocrisy in cosying up to its former enemies.

FdI does not need to grow hugely to claim leadership of the right-wing coalition that fought the 2018 general election. It now attracts 17% of the vote, against the League’s 23%. If, as is likely, the same right-wing coalition as in 2018 is formed for the 2023 general election, and were it to win, then Meloni could, in the event of the FdI securing just one vote more than the League, claim the prime ministership.

As the official opposition in the period to come, FdI will get plenty of television coverage. The party will also chair important Parliamentary committees, including the one overseeing the public service broadcaster RAI.

A thorn in their side

The League is in an impossible situation. It will probably keep ‘one foot in and one foot out of government‘, becoming a thorn in Draghi’s side. The League will obstruct initiatives the right-wing electorate may find tough to stomach, although it lacks the power to block them entirely. For each percentage point the party loses, pressure will mount for the leadership to protest more loudly. If FdI continues to grow, the pressure will be even greater.

Governing with a heterogenous majority of sworn enemies responsible for managing enormous sums of money from the EU’s Recovery Fund was never going to be easy

So, expect Salvini to engage in much infighting during the months ahead. He will choose his enemies and friends in government with great care. In fact, the show has already begun. Before Draghi’s first speech in Parliament, Salvini attacked the Minister of Health and his collaborators over the possibility of a new lockdown.

Governing with a heterogenous majority of sworn enemies responsible for managing enormous sums of money from the EU’s Recovery Fund was never going to be easy. But the problems besetting the M5S and League make that situation decidedly worse. Infighting between the governing parties looks likely to be a permanent feature of the Draghi government.