Coronavirus Shapes Belgium’s Government and Populist Opposition

By Judith Sijstermans (PiAP Belgium focused Research Fellow) – this piece originally appeared on EA Worldview

Amid the Coronavirus pandemic, acting Belgian Prime Minister Sophie Wilmès has formed an emergency government with full powers, including further authority in the emergency.

The minority government received support from nine out of twelve Belgian parties in the federal Chamber of Representatives on Tuesday. Only Flemish nationalist party the Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (N-VA), left wing party the Partij van de Arbeid (PVDA), and the right-wing populist party Vlaams Belang (Flemish Interest, VB) objected.

On the surface, this is a show of unity in the Belgian Government. But a deeper look at the state of play and the VB’s opposition uncovers shaky political ground.

Maneuvers over a Government

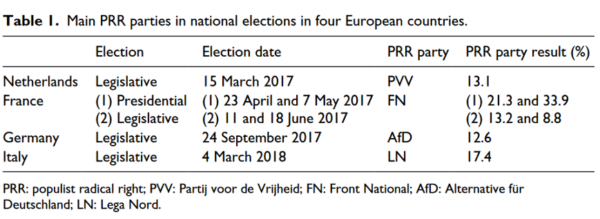

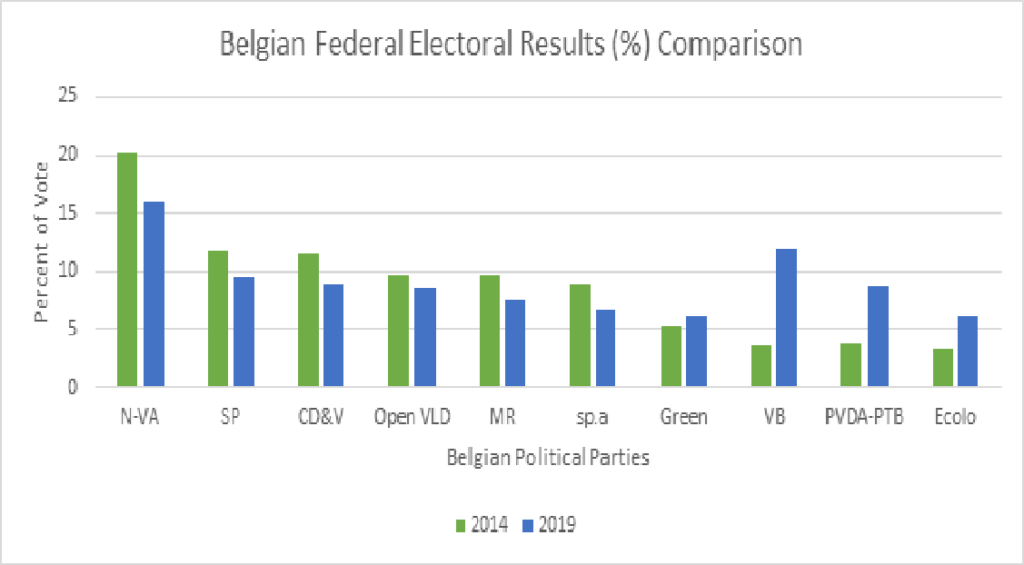

Belgium has been without a fully-empowered administration since the May 2019 elections, given their mixed results. These not only exacerbated the difference between the Flemish and Walloon regions of the country, but also repudiated the sitting government and punished its parties, Mouvement Reformateur (MR), Open VLD, and Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams (CD&V). The vote share of the N-VA, which left the government over disputes about the UN Migration Pact, was significantly reduced.

During negotiations, the outgoing government remained as a caretaker administration. Over the weekend of March 14, with the outbreak of Coronavirus and the need for urgent measures, chatter began about an emergency government. All party leaders, except those of the Vlaams Belang, discussed the possibility.

Until that weekend, government “formateurs”, responsible for negotiating a coalition, were still considering many coalition options. The leading option on the table at the time was a “Vivaldi” administration (because its four components represent the composer’s Four Seasons): Francophone socialists, liberals, and Greens and Flemish socialists, liberals, Greens, and Christian Democrats. However, after a long series of attempted negotiations, the only possible arrangement was to further empower the caretaker government.

See also Belgium’s Populism and Polarization: Europe in Miniature?

Coronavirus and Competence

While the news cycle and politics are consumed with Covid-19, time has not stopped. N-VA leader Bart de Wever forecast, “There won’t be much to argue over the next few months. The question is: how do you prepare for peace?”

Flanders’ populist radical right party Vlaams Belang is not waiting for the end of the crisis to push against the government. And it has backing: in a poll commissioned by Belgian news outlets and released on 14 March, the VB is the clear Flemish winner with 28% of the vote. The N-VA suffers the biggest losses, polling 5% below their May 2019 electoral results.

Because of a cordon sanitaire upheld by all other Belgian parties since 1989, the negotiations to organize an emergency government did not include VB. But in May 2019, the party came the closest in its history to governing at the highest level. There were discussions to form a government with N-VA leader de Wever, and VB leader Tom van Grieken met the Belgian King.

Since autumn 2019, the VB has used the rhetoric of “Mission 2024”, seeking to become the largest Flemish party at the next elections, which would give them the right to be the first party to begin negotiations in Flanders. In their push against the cordon sanitaire and their opposition to the emergency government, Van Grieken wrote an open letter to Wilmès this weekend:

I do not agree with the fact that you, even today, divide citizens into first and second class citizens just because they voted for the “wrong” party. I hope that you withdraw your heartless decision and that the next meeting does involve the country’s second largest party.

Coronavirus provides an opportunity for the Vlaams Belang to project its ability to make policy, to argue that it is ready for the transition from an opposition to a governing party. This is the theme of leader Van Grieken’s new book, released on March 11th, En nu is het aan ons (“And now it is up to us”).

Since the 2019 elections the party has slowly been building up its staff resources. These have focused on policy experts, reflected in a new structure linking staff across the party and Belgium’s different legislative bodies.

In the case of Covid-19, the party has sought best practice and pointed at South Korea and Singapore as examples of good governance. It has criticized Belgium’s acting government and urged more radical measures more quickly. The party proposed a committee to scrutinize the government’s actions to ensure that the “coronavirus does not become a corona-coup”.

Gerolf Annemans, VB MEP and former leader, explained on Twitter:

This is a glorified coup by Magnette [leader of the Parti Socialiste] to push through his Vivaldi construction. Abusing the Corona crisis to try to silence the opposition. One of the most outrageous manoeuvres ever seen. Why, N-VA?

“I Told You So”

Vlaams Belang has used the virus to validate many of its key ideological stances: anti-immigration, law and order policies, and sub-state nationalism. Closing the borders has been celebrated and the party has urged further action, such as placing soldiers at the border. Long-time VB figurehead Filip Dewinter tweeted, when a terror suspect was arrested by border control:

Apparently it takes a Corona crisis to make clear that controlled borders are necessary and useful: we keep out intruders (corona, illegal immigrants, drug dealers…) and the bad guys (terrorists, criminals …) in — behind bars!

The party’s representatives have pointed to the perceived unfair distribution of health care resources between Flanders and Wallonia, criticized China for “causing” the Coronavirus crisis, and pinned unrest on the streets and in stores on young migrants.

The Covid-19 crisis, alongside long-term government deadlock and recent polls, provides a window of opportunity for the VB. The party’s framing of the crisis reflects both long-term policy goals and an accelerating push towards breaking Belgium’s cordon sanitaire.

In the time of Coronavirus, governments around the world have sought to suspend political conflict in the name of unity. But for the VB, pressure on the government remains crucial.