In Part 1 of the Hospital Charity takeover, Frances Williams provides a visual analysis of fundraising posters, considering the past, present, and future of charity in the NHS.

An idyllic scene of ‘Merrie Merrie England’ makes appeal for hospital funds on a poster of 1917. At this point in time, voluntary hospitals relied heavily on charitable donations alongside receiving patient payments and subscriptions. A maypole sits centre stage, offering a swirl of colourful ribbons. Yokels raise mugs of ale in good cheer while swallows fly over a far-off building – recognisable on closer inspection as The Brighton Pavilion. Her Royal Highness Princess Alice will oversee proceedings, it is promised.

These class-bound gaieties play with quintessentially English motifs, yet the charitable object in question is a local hospital: The Royal Sussex County. It makes for a nostalgic fiction built around attachments to country and king. Most strikingly, perhaps, there is no hint of the devastating loss of life brought about by world war being waged in nearby France.

1917 Merrie Merrie England fair for the Royal Sussex County Hospital. Image courtesy of Brighton & Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust and thecrucible.org.uk.

Hauntings and Border Crossings

Hospitals can be read as ‘haunts’, I’ve proposed elsewhere, institutions through which recurring affects and political mobilisations attach and might be traced (Williams 2020). I examined the unfinished architectural plan of one London hospital, St. Thomas’ (or ‘Tommies’ as it is affectionately termed) to show how absences can, rather oddly, exert presences. Political theorist Mark Fisher wrote of ‘lost futures’, suggesting that ‘hauntology’ can help us describe ‘that which acts without (physically) existing’ and which gives rise to ‘reverberative events in the psyche’ (Fisher 2013: 48). The medical anthropologist Sarah Pinto directs us more specifically towards hospitals as sites of study, since they ‘can signal lost civic spirit’ (Pinto 2018). Referencing Foucault, she describes the hospital as ‘iconic of the instantiation of modern power,’ embodying ‘unevenly distributed resources’.

Fundraising posters are an intervention into civic spirit and rooted in unevenly distributed resources. Through these posters, hospitals and their associated charities craft an image to prompt donations from an imagined public. The poster described above is one of many artefacts gathered together in a visual timeline from 1910 to the present day, curated by researchers as part of the Wellcome Trust ‘Border Crossings’ programme.

The timeline of posters begins before and continues through the creation of the NHS whose foundational premise rested on the use of general taxation to pay for healthcare for all. It’s commonly understood that charitable donations are only used to ‘top-up’ existing state funds (Mohan & Clifford 2024). But as John Mohan notes, in practice, ‘this is a difficult border to demarcate’ (2024: 545). Any substitution of one funding source by another is regulated by convention and is ‘not codified in law’. Mohan argues that accounts of ‘the positive and negative aspects of charitable effort are often partisan and lacking in evidence’ (Iacobucci 2024). In this context, there is a vital role for humanities research in unpicking the broader socio-cultural effects of these efforts over time.

Winners and Losers

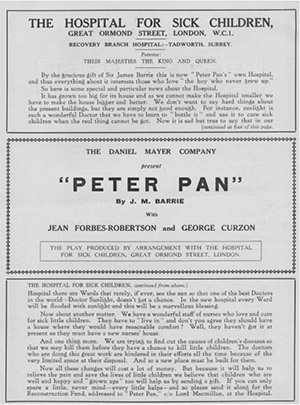

Prior to the creation of the NHS, a patchwork of voluntary hospitals were funded to differing degrees, with some localities at distinct (dis)advantage to others. Key London hospitals had amassed large fortunes based on the generosity of wealthy patrons, including early forms of celebrity endorsement. In 1929, for example, children’s author J.M.Barrie donated all the proceeds of his book, Peter Pan, to Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH).

When GOSH launched a campaign in 1930 to raise funds for a new hospital of Modernist design, the health benefits of ‘Doctor Sunlight’ were much vaunted. Though transparency was a goal easily achieved by way of glass windows, the amount of royalties received through Barrie’s gift would be kept confidential. While cultivating rich donors, GOSH’s campaign made appeal to a more common humanity: ‘Surely everyone who loves children… will help us,’ https://more.bham.ac.uk/border-crossings/2023/01/10/1929/ poster implores, reminding that it is ‘our solemn duty to the children of today and tomorrow’ to give a gift be that ‘great or small’.

Promotion for Peter Pan play and appeal for funds for development of Hospital. Image courtesy of Great Ormond Street Hospital

GOSH was one of four other London-based hospitals whose incomes were boosted by historic endowments. These proved key in negotiations around the scope of the new NHS when it was instituted in 1946. Nye Bevan wanted to liberate healthcare from ‘the caprice of charity’ since, he argued, it was ‘repugnant to a civilised community to have to rely on private charity’ he asserted (Bevan, 1946). The suspension of hospital endowments, his opponents countered, would sever valuable community connections between hospitals and locality, also discouraging future donations.

Bevan was forced to compromise on this point, allowing teaching hospitals in London to retain their endowments because they were engaged in research. Not able to lever capital for new buildings on a scale previously possible, however, the issue remained contentious. Long in the planning, a focus of frustration became the construction of a new tower for Guys Hospital in the 1960s, which ambitiously aimed to become the tallest in the world.

Thrusting heights are picked out in shadow and light on a monotone poster of this period. Guys Hospital used its endowment funds to explore ambitious designs for a new tower by a range of international architects. But they had to offer to provide substantial financial assistance to enable completion of the projection the early 1970s as recession hit. This offer arguably acted to ‘bounce the Ministry into giving approval’, a border transgression conceded by central government.

Other ‘border crossings’ were borne of community organising against the pressures of spending cuts and recession. The closure of smaller NHS hospitals in the 1970s allowed old buildings to be used in new ways. Patients became campaigners in the case of The Mildmay hospital deemed too small to be economically viable in 1982. It was revived as a charitable nursing home that existed outside the NHS, becoming Europe’s first hospice for people with HIV and AIDS in 1988.

The milestone Health Services Act of 1980 permitted NHS bodies to engage directly in fundraising, after which the number of charitable campaigns grew considerably.

Reverberation and resonance

Most recently the COVID-19 pandemic saw grassroot initiative shade, almost unnoticed, into professionally coordinated campaigns. The symbol of the rainbow sprang-up in folk art form, an emblem of public support for healthcare workers. The rebranding of a membership body, NHS Charities Together, proved left them well-placed to capitalise on ‘public outpourings of gratitude’. Whether staff morale and well-being could be considered ‘essential’ to workforce efficiency, or added bonus, led to further questioning of how, and if, charitable funds could be used for this purpose.

Border disputes, such as these, prompted counter-campaigners to reassert that the ‘NHS is not a charity’. They cast the NHS Charities Together campaign as a mask behind which chronic underfunding and increasingly unequal services could be hidden and allowed to continue. Arnold-Forster and Gainty flipped the charitable model to conclude that ‘in order to save the NHS we need to stop loving it’.

Between the rainbow motif and the maypole’s colourful ribbons, then, might expressions of love of country find resonance across time? One through which repression of a sense of loss can be observed – as joyful burst? Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic was cast as a ‘war’ with healthcare workers ‘heroes’. The veteran figure of Major Tom Moore was elevated to celebrity status, raising over 35 million pounds for his sponsored walk alone.

About the author

Frances Williams brings experience of working in gallery education and the field of Arts in Health. Between 2016-2019, she took-up a doctoral scholarship at Manchester Metropolitan University where she studied Arts in Health in relation to devolution (2016-2019). She is the author of the book When Was Arts in Health? A history of the present (Palgrave, 2022).

References

Arnold-Forster, A & Gainty, C. (2021) To save the NHS we need to stop loving it, Renewal, 29(4), 53-61.

Bevan, N. (1946) Hansard (Commons), 5th series, vol. 422, 30 April 1946, cols. 46‒7.

BMJ, (2024) Hospitals serving England’s most deprived patients generate proportionally less private income, study shows. 384. 419.

Fisher, M. (2013) The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology. Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 5(2): 42–55.

Harris, B. & Cresswell, R. (2024) The legacy of voluntarism: Charitable funding in the early NHS. The Economic History Review. Volume77, Issue2. Pages 554-583.

As social imaginaries for the future draw on those of the past, these are some of the contested narratives and figures thrown up by the visual representations of the Border Crossings timeline. Rather than marking a revolutionary intervention, the NHS has always accommodated charitable funding: these funds have shape-shifted to find form within – and around – an array of fiscal, ethical and statutory frameworks. This project suggests that only through paying careful attention to how we relate to the NHS and its symbolic values can we begin to properly weigh and judge the emotional and monetary investments we place in it.