In Part 3 of the Hospital Charity takeover, Hannah Blythe analyses United Sheffield Hospitals’ annual reports and explores the boundary between charity and state-funded healthcare in the first decades of the NHS

In 1946, Aneurin Bevan articulated his vision for a nationalised health service. He argued that incumbent provision had ‘grown up with no plan, with no system’ and needed to be replaced with a ‘universal’ and ‘efficient’ service that did not rely on the ‘caprice of private charity’. Yet, he accepted that ‘the voluntary hospitals of Great Britain have done invaluable work’, and allowed teaching hospitals to retain charitable endowments (HC Deb 30 April 1946). How did these hospitals’ leaders reconcile their continued use of charity with the state’s emphasis on efficiency and planning? The Governors of the United Sheffield Hospitals (USH) harnessed the custom of publishing annual reports to frame their use of endowment money. These documents featured visual devices – photographs, statistical graphs and infographics – to fuse old charitable traditions with new approaches to financial management and efficient planning of health services (Fig. 1).

Britain’s pre-NHS teaching hospitals were funded by charitable means. These large voluntary hospitals were prestigious institutions in which patient treatment and medical research went hand in hand. Nationalisation came with reassurances that teaching hospitals would keep their prestige and research capacity. Thus, while the Treasury was to fully cover these hospitals’ costs, those in England and Wales were also allowed to keep all of their existing endowments, although active fundraising for donations was severely restricted (H). Bevan justified this decision on the basis that teaching hospital endowments were ‘distinguished, to a very large extent, from the endowments of general hospitals because … [they] are earmarked for special purposes, such as cancer research (HC Deb 22 July 1946).

Fig. 2: Sheffield Archives: NHS28/1/2/1/3

The USH was formed in 1948 when former-voluntary hospitals of Sheffield were nationalised and united under a single Board of Governors. The Board embraced the NHS while promising to continue the ‘worthy traditions’ of their formerly charitable institutions (AR, 1949: 12). One of these traditions was the production of annual reports, which the Board published until the USH was abolished with the 1974 NHS reorganisation.

Annual reports had been a mainstay of charity organisation throughout the preceding centuries, being used to publicise voluntary organisations’ activities, petition support for charities’ causes, and fundraise. While historians frequently rely on annual reports for information about organisations’ activities, personnel and finances (e.g. Borsay, 1991), few have positioned these documents as an object of enquiry or dedicated scholarship to their form and presentation. Yet, these documents’ narrative, statistical and image components all afford insight into the social, financial and emotional relationships and motivations involved in welfare administration. The USH’s Governors designed their reports to build common ground between the philanthropic supporters and the state funders of Sheffield’s teaching hospital. (Fig. 2.)

A small number of interdisciplinary accounting and business studies use historical methods to consider the social and financial roles played by different components of annual reports produced by eighteenth and nineteenth-century charitable institutions. Lisa Evans and Jacqueline Pierpoint (2015) analyse the written narratives about “fallen women” admitted to Edinburgh Magdalen Asylum between 1801 and 1914. They assess how these narratives were used to frame the asylum’s leaders’ ‘rescue work’ to garner support for their cause and find domestic service employment for the women they hoped to rehabilitate from prostitution. While Evans and Pierpoint focus on written narratives and literary devices, William J. Jackson (2012) examines annual reports’ presentation of financial information. He highlights how, in the mid-nineteenth century, the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh’s administrators developed easily-searchable subscriber lists to maximise the hospital’s income. By making it easy for readers to search for individuals’ contributions, the reports encouraged larger payments from those concerned about public perceptions of their wealth and benevolence. Attending to how information was presented in annual reports reveals how these documents marshalled different actors’ relationships with health and well-being charity. The USH Governors employed photographs, graphs and infographics regarding endowment money to appeal to both philanthropic supporters and government departments. These images thus helped to incorporate longstanding charitable practices into state-led post-war health administration.

The USH’s reports present detailed information about how the endowment was managed. They feature annual accounts and contain increasingly detailed breakdowns of endowment expenditure, in which the Governors categorised their charitable outlay into ‘research and allied projects’; ‘patients’ welfare and amenities’; ‘staff welfare and amenities’, and ‘other’. During the1960s, categories of ‘contribution to capital expenditure’ and ‘medical equipment’ appeared. Financial tabulations and written commentary were accompanied by photographs, graphs, and infographics. While most of the pages focused on Treasury-funded activity, a disproportionate amount of space was dedicated to the endowment. Indeed, between 1950-51 and 1972-73, endowment spending constituted between just one and three percent of the USH’s total outgoings. The Board wished, despite the endowment’s small contribution to expenditure, to publicise its efficient and prudent application and hence justify its continued use.

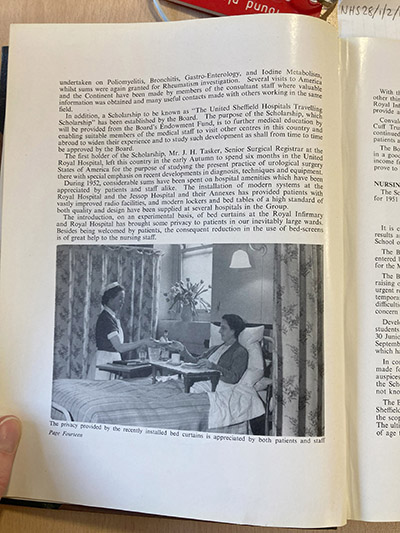

Photographs were used throughout the period to promote the benefits the endowment brought to patients and employees. For example, the 1952 report featured Figure 1 with the caption, ‘The privacy provided by recently installed bed curtains is appreciated by both patients and staff’ (AR, 1952: 14). A nurse and patient pose in a serene interaction, presenting the ward as a calm environment for recuperating from medical intervention. The flowers, window and light provide a bright and homely feel, as though the patient is in her own bedroom with the curtain walls affording privacy in reassuring proximity to professional nursing staff. Between 1952-53 and 1957-58, the USH spent £14,450 (deflated to 1949 prices) on bed curtains, and this photograph portrays the benefits. (Fig 3)

However, exhibiting the items bought with voluntary money was not enough to justify the persistent use of charity in the nationalised health service. In the post-war years, Ministry of Health and Treasury directives emphasised the need for an efficient, organised and dependable NHS. State reliance on economic planning was woven into the health service (O’Hara, 2006: 167-204). As Stephen M. Davies highlights, following the publication of the Guillebaud Report in 1956, which declared that high amounts of expenditure were necessary to maintain adequate standards, the Government pushed management techniques and productivity science to ensure that the large sums dedicated to health care were spent efficiently. Government initiatives included the creation of a Ministry of Health statistics department in 1955 and the establishment of the Advisory Council for Management Efficiency (ACME) in 1959. The USH’s management showed great interest in the state’s efficiency and planning drives, with the Chief Administrative Officer requesting 300 copies of the statement of ACME’s aims upon its launch (Davies, 2017: 47-68).

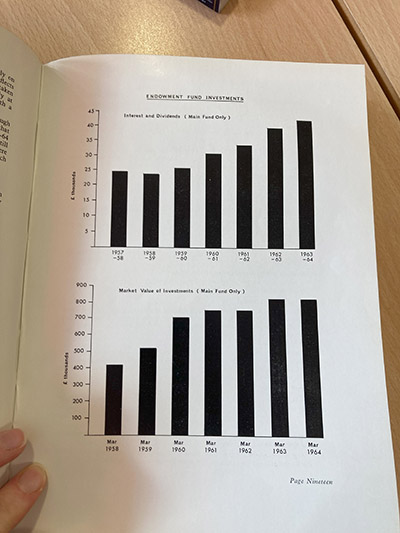

The USH’s Governors wished to retain voluntary traditions but needed to distance themselves from the ‘caprice of private charity’. Thus they employed financial diagrams and infographics to communicate their strategic management of the endowment to an interested public, philanthropic stakeholders, and government administrators. These images were designed to reconcile the tradition of healthcare charity, with its connotations of unpredictability and the whims of donors, with the state’s emphasis on financial efficiency and reliability. The Governors embraced statistical representations of the USH’s financial management. For example, the 1964 report contained a bar chart (Figure 2) representing the thousands of pounds raised by the endowment’s Investments Committee through astute financial management (AR, 1964: 19; AR, 1954: 16).

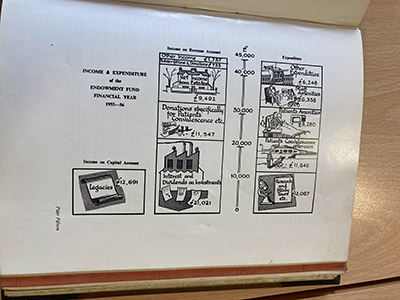

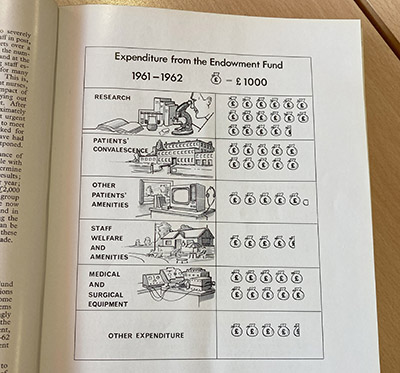

More elaborate infographics combined statistical breakdowns of endowment income and expenditure with playful illustrations of the attendant benefits. Figures Three (AR, 1956: 15) and Four (AR, 1962:17) show infographics from the 1956 and 1962 reports. Figure Four tabulates the different kinds of endowment spending for the financial year 1961-62. Drawings of money bags represent £1,000 of expenditure each. The cartoon images quickly and boldly conveyed that the endowment allowed complex research, high-tech equipment, facilities for treatment and care, and improvements to staff working conditions and patients’ experiences. The infographic’s statistical element indicated that charitable money was now part of the NHS’s efficient financial management and economic planning. (Fig. 4)

Of course, these infographics were intended to entice donations, communicating reassurance that subscriptions, donations and legacies would be productively invested in a well-thought-out spending regime. The playful images were designed to engage the reading public and interested philanthropists. They here evoked a sense of local pride and productivity, with the drawing of a smoking factory in Figure Three depicting charitable investment in Sheffield’s industries as a dependable source of income. These infographics allowed the Governors to continue their tradition of soliciting donations through annual reports, while presenting their administration of charitable moneys as part of the state’s project to create a planned and efficient nationalised health service, despite official restrictions on NHS bodies directly engaging in fundraising.

The visual elements of the USH’s annual reports reflect Governors’ efforts to combine long-standing charitable traditions with the new age of nationalised health services. These images celebrated voluntary support and local resources for the hospital, thereby soliciting donations while simultaneously engaging in the state’s mid-century push for NHS financial efficiency, to be achieved through embracing statistical techniques and prudent investment in modern infrastructure and equipment (Davies, 2017: 53).

About the author

Hannah Blythe is a Research Fellow at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), where she works on the Border Crossings project. She is a health humanities researcher with interests in charity, the NHS and mental health, and prior to joining LSHTM she completed a PhD on the history of mental health charities at the University of Cambridge.

References

Borsay, Anne. (1991). Cash and Conscience: Financing the General Hospital at Bath 1738–1750. Social History of Medicine 4(2): 207-229.

Davies, Stephen. (2017). Promoting Productivity in the National Health Service, 1950 to 1966. Contemporary British History 31(1): 47-68.

Evans, Lisa and Jacqueline Pierpoint. (2015). Framing the Magdalen: Sentimental Narratives and Impression Management in Charity Annual Reporting. Accounting and Business Research 45(6-7):. 661-690.

Harris, Bernard, and Rosemary Cresswell. (2024). The Legacy of Voluntarism: Charitable Funding in the Early NHS. The Economic History Review 77(2): 554–583.

HC Deb (30 April 1946). vol. 422 col. 44-63. Available at: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1946-04-30/debates/62dd8934-2b79-4a9b-9b51-94e812c79fab/NationalHealthServiceBill (Accessed 10 October 2024)

HC Deb (22 July 1946) vol. 425, cols. 1793‒4. Available at: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1946-07-22/debates/029af8ff-1d91-401a-9fd8-82e1546b4642/Clause7%E2%80%94(EndowmentsOfVoluntaryHospitals) (Accessed 10 October 2024).

Jackson, William. (2012). “The Collector Will Call”: Controlling Philanthropy through the Annual Reports of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, 1837–1856. Accounting History Review 22(1): 47–72.

O’Hara, Glen. (2006). From Dreams to Disillusionment Economic and Social Planning in 1960s Britain, 167-204. London, Palgrave Macmillan.

The United Sheffield Hospitals Annual Reports 1949-1974, abbreviated to AR, Sheffield, 1949, Sheffield City Archives, NHS28/1/2/1/1- NHS28/1/2/1/17.