By Dr Steph Haydon and Dr Francesca Vaghi

In December 2023, the Border Crossings team hosted the Symposium: ‘Charity and Children’s Hospitals: Exceptionalism, Experiences and Welfare,’ at the University of Strathclyde. The event was inspired by an emerging theme from the Border Crossings project – that children’s hospitals, and children in hospitals, are often exceptions in terms of how we talk about them, how they are portrayed in media and fundraising campaigns, and how they tend to receive more funds than other types of hospitals, patients, or charitable organisations. The Symposium aimed to bring these conversations to the forefront, so that children’s experiences and contributions do not remain at the margins. Over the day, we had 13 fantastic speakers, split across four panels. Below, we attempt to consolidate the many conversations and debates of the day into three overarching themes.

Theme 1: There is considerable heterogeneity within the charity and children’s hospital landscape

Our initial framing of the Symposium began with the perceived exceptionalism of children’s hospitals from other types of hospitals and charitable organisations. However, papers presented at the Symposium showed the considerable differences that exist within the children’s hospitals landscape.

Speakers touched on the differences that geography makes to the exceptionalism of children’s hospitals. In the UK, for example, London hospitals often receive more attention, publicity, and money than in other areas of the country. Differences of regional management and organisation affects how much government funding is allocated to hospitals, and availability of services, shaping hospitals’ demand for additional charitable resources to meet funding gaps. Perspectives from international speakers highlighted that culture shape people’s understanding of charity, and the roles it can, and should, play in providing services to children in hospital.

Class background also matters; working class people during the 1950s and 1960s had very different attitudes towards their children, and expectations over their care, compared with middle- and upper-middle- class people. The way we perceive and portray children’s hospitals donors also varies by class, with elite funders often receiving greater recognition. Yet, many groups (from across class, gender, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds) contribute to, and fundraise for, children’s hospitals, including children, past patients, and patients’ parents. Each have different experiences of children’s hospitals, motivations for giving, and expectations of the donor/fundraising relationship. All make key contributions to the causes they support, although the extent to which they can shape fundraising agendas and strategies varies.

Theme 2: Across the language and levels of appeals for children’s hospitals, patients are central

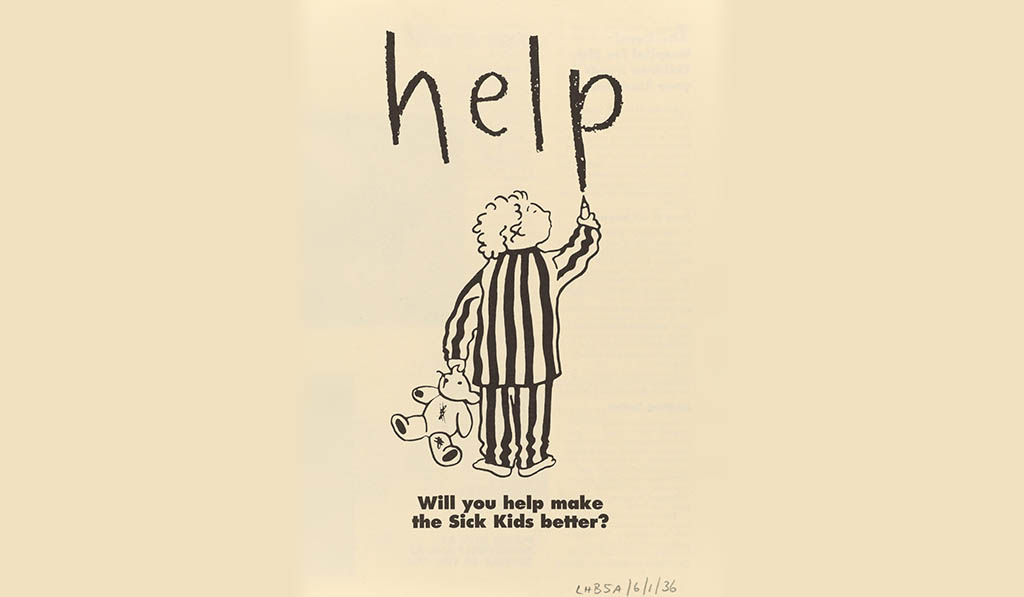

The language of charitable appeals is typically driven by what is most likely to ‘move’ donors. But children, too, can be involved in deciding this language. For example, at the Edinburgh Children’s Hospital, charity appeals are no longer framed as in aid of ‘sick kids’, after consultations with child patients showed they did not want to be referred to as ‘sick’.

The image of the child is also central across different levels of need that may be portrayed through fundraising appeals. At the patient level, campaigns can be targeted towards helping individual patients, such as to support travel abroad for treatment. At the hospital level, appeals fundraise for buildings, extensions, redevelopments and equipment. In both cases, caring for children is portrayed as having wider public benefits. Whether appeals are defined in aid of an individual (i.e. patient-level), institution (i.e. hospital-level), or wider society, imagery of children, and the portrayed importance of children, remain at the fore.

The many reflections that speakers (and attendees) shared on the ethics of appealing to emotions in charitable fundraising were welcome. There has been a gradual shift, from viewing children in hospitals as passive victims, towards a recognition of their agency and voices. On the other hand, ongoing limitations to full participation, mainly posed by children’s generational status, were also evidenced. For example, in Finland, an unprecedented expansion of charitable activity within healthcare gained prominence through the establishment of the New Children’s Hospital Foundation (NCHF). Children’s lack of political leverage is perceived, in this case, as one of the reasons why provision of specialised paediatric services is not always prioritised and is devolved to the charity sector, and simultaneously as a development in provision that would not be met with much resistance because “children can’t vote.”

Theme 3: The relationship between charity for children’s hospitals and the State is constantly renegotiated

Our final theme concerns the roles and responsibilities of the state in providing for children’s hospitals, the roles and responsibilities of charity in providing for children’s hospitals, and how the two relate to one another.

Over the course of the day we heard about past debates regarding state authority over private donations and potential tensions between public and private interests.

We also heard about, and engaged in, more enduring debates about what charity can and should be permitted to do. Does charity supplement restricted state funds, meeting shortfalls and widening the income base of hospitals? In other words, does it provide the cherry or the icing on the top of the cake? Is charity a response to failures of the state, providing a service that should – but is not or has not been – state provided?

Or, conversely, is charity absolving the state of its responsibility, distorting funding for children’s hospitals and embedding a postcode lottery, such that where you live affects the services available to you and the quality of them? If charity ‘should’ be limited to the icing on the cake, what counts as the icing as opposed to more ‘core’ ingredients, and who gets to decide this?

As our speakers and guests reminded us, most people who fundraise for children’s hospitals would happily be out of a job. But until they are adequately funded and provided for through other means, charity will continue to play a significant role.