Jenny Uglow: ‘A Year with Gilbert White’

Summer Weinrebe Lecture

Tuesday 17 June 2025, talk at 4pm, drinks reception 5.15. University of Birmingham Arts Building, First Floor, Main Lecture Theatre.

Our annual lecture, a collaboration between Arts of Place and OCLW, brings together thinking about place with some of the most exciting current work in the fields of biography and life-writing. Lives happen in places; places shape lives and have lives of their own.

On the 17th June we welcomed Jenny Uglow OBE to speak about her new book A Year With Gilbert White: The Story of a Nature Writer (to be published by Faber this September). Jenny is the author of highly acclaimed biographies and histories, including the classic of Midlands history The Lunar Men: The Friends Who Made the Future. The talk formed part of our ‘Pioneers of Local Thinking’ series.

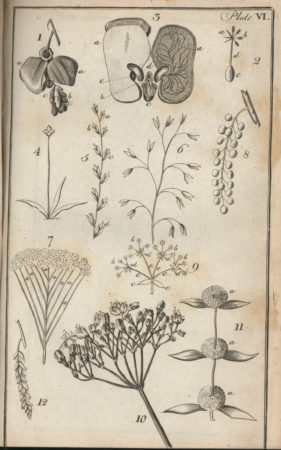

“In 1781, Gilbert White was a country curate in the Hampshire village he had known all his life. He kept journals for many years and was now halfway through completing his Natural History of Selbourne – in print since 1789, paving the way for later naturalists. No one had written like this before, with such close observation, humour, and sympathy.

Often called ‘the father of ecology’, White noted the results of ‘watching narrowly’ in his Naturalist’s Journal. Through this we follow the seasons, from frost to drought, noting everything from the migration of birds to the sex lives of snails, and the vagaries of village life – a determined local record, imbued with a profound sense of place.”

*

A former editorial director of Chatto & Windus, and previous Chair of the Council of the Royal Society of Literature, Jenny Uglow is a biographer and historian. Her books on scientists, writers and artists include The Lunar Men: The Friends Who Made the Future, In These Times: Living in Britain through Napoleon’s Wars and Nature’s Engraver: A Life of Thomas Bewick, as well as Edward Lear: A Life of Art and Nonsense. Her book on Gilbert White will be published in September 2025.

Featured image: Eric Ravilious, The Tortoise in the Kitchen Garden, from The Writings of Gilbert White of Selborne, ed., H. J. Massingham, (London: The Nonsuch Press, 1938), Private Collection.

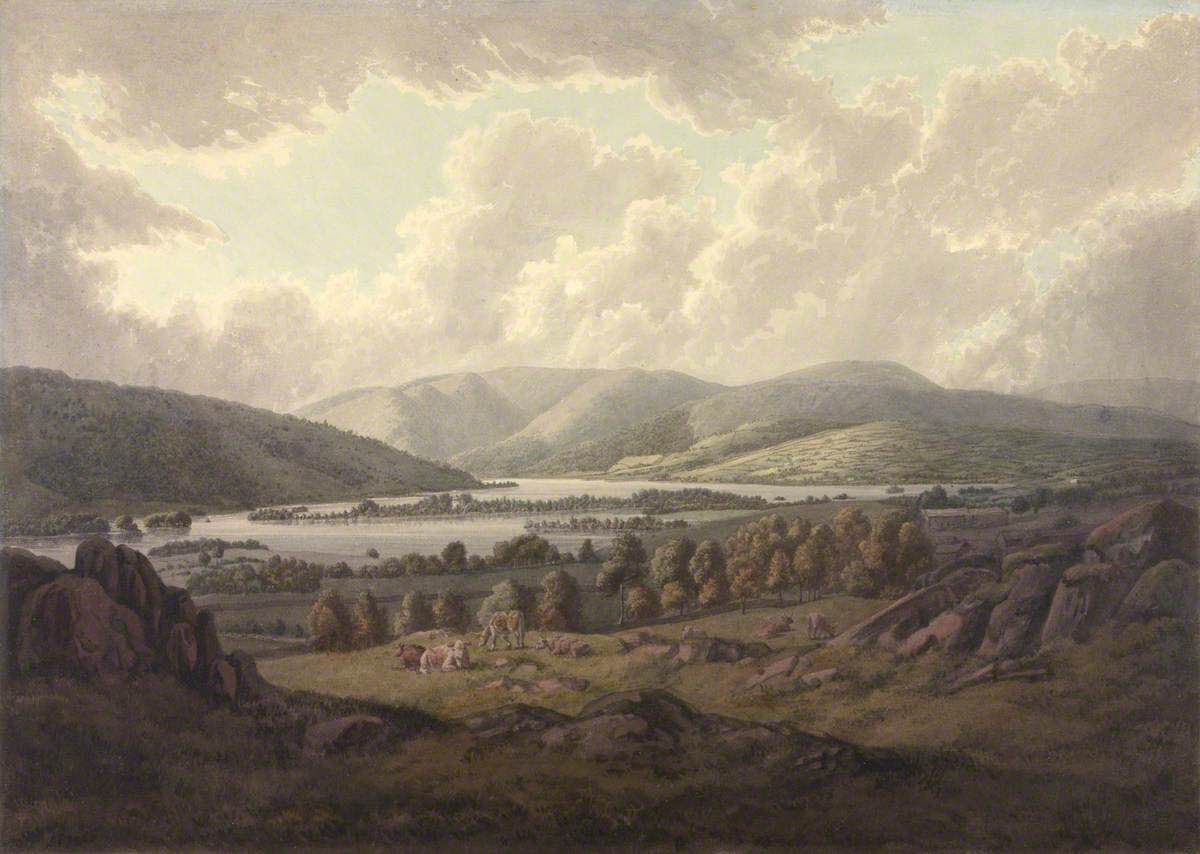

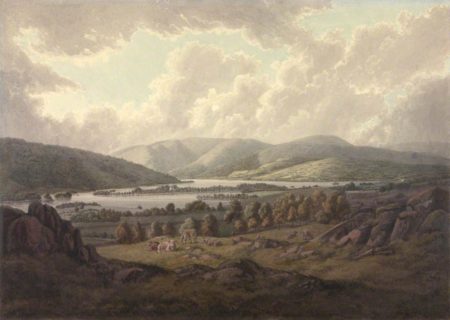

Description image: Engraving after Samuel Hieronymus Grimm, East view of Selborne from the Short Lythe.