“To the Lakes!”: Local artistic perspectives

with guest speaker Jeff Cowton MBE, Principal Curator & Head of Learning at the Wordsworth Trust

Monday 20 May with Jessica Fay in response and conversation.

On 20 May, Jeff Cowton joined us to discuss the Wordsworth Trust’s exhibition ‘To the Lakes!’, a study of how the Lake District attracted outside tourists and artists from around 1750 onwards, and how this tourism has shaped both the art it produced and the place at its centre. As Jeff makes clear, the work of visiting artists taking picturesque tours of the area was partly shaped by local writers and artists. Jeff focused on the work of two artists: William Green of Ambleside and Joseph Wilkinson. He explored their challenge to the pictorial conventions surrounding landscape in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, and their engagement with the emergent tourism industry.

Watch the recording of this talk below and read on for some highlights.

Introducing his latest exhibition, Jeff invoked the finest poet of our age: yes, Taylor Swift of course, who sings ‘Take me to the lakes’. Unfortunately, this is followed by the line ‘where the poets went to die’. Jeff set out to chart more cheery and perhaps more lyrically nuanced territory. He turned our attention to tourists of the past and the present and how they have made the Lake District what it is today.

William and Dorothy Wordsworth’s lives at Dove Cottage were shaped by tourism, as William writes in ‘The Brothers’:

These Tourists, heaven preserve us! needs must live

A profitable life: some glance along,

Rapid and gay, as if the earth were air,

And they were butterflies to wheel about

Long as the summer lasted: some, as wise,

Perched on the forehead of a jutting crag,

Pencil in hand and book upon the knee,

Will look and scribble, scribble on and look,

Until a man might travel twelve stout miles,

Or reap an acre of his neighbour’s corn.

Jeff turned first to Joseph Wilkinson (b. 1763), a Carlisle-born deacon who lived in Ormathwaite Hall north of Keswick. He left the lakes in 1803 to live in Norfolk but not before creating a substantial volume of landscape prints of Northern Scenery, with a title page created by William Marshall Craig featuring labouring figures in the landscape (a rarity within the landscape conventions of the day). Wordsworth was enlisted to write an introduction to Wilkinson’s, and he later voiced his embarrassment that the landscape would not meet the exacting standards of his patron Sir George Beaumont. Jeff expertly guided us through the ‘holy grail of Joseph Wilkinson studies’: a fascinating progression from preparatory drawing to watercolour and three prints with various levels of colour added.

Next Jeff turned to William Green (b. 1760) who trained in Manchester and later moved to Ambleside to create a prolific career as a landscape draughtsman and printmaker. Although Green was evidently conscious of the conventions of the picturesque, he also sought to depict a faithful record of landscape and architectural features in Ambleside and its area. Jeff highlights this tension between the pictorial and the practical by presenting us with an extract of an account of a tourist, Green, and his daughter discussing Stockghyll Force:

‘See now,’ observed Mr. G. ‘that tree shuts out the prettiest part of the cascade, while there wants one to hide the deformity of that other bank; be-side, that wood on the declivity of the other hill, which threw so fine a gloom over the whole glen, is now vanishing beneath the woodman’s axe; and a certain degree of poverty will be the natural consequence.’ ‘You will excuse,’ said Miss Green ‘my father’s enthusiasm for his darling art. He knows no world, but that in which a painter lives. Trees, with him, have no other use but that of giving softness and effect to a picture. The meadows were created for foregrounds and the hills were designed for distances. Rivers only roll along to brighten up the landscape; and cattle graze only to give life to his drawings. When any thing, therefore, is out of place, in a picturesque point of view, it excites his criticism, notwithstanding its utility in other respects.’

Jeff compared this to Thomas Gray’s notorious description of Grasmere life in 1763 where ‘all is rusticity and happy poverty’ and ended by sharing with those us in the room a small collection of prints produced by Green in the 1790s.

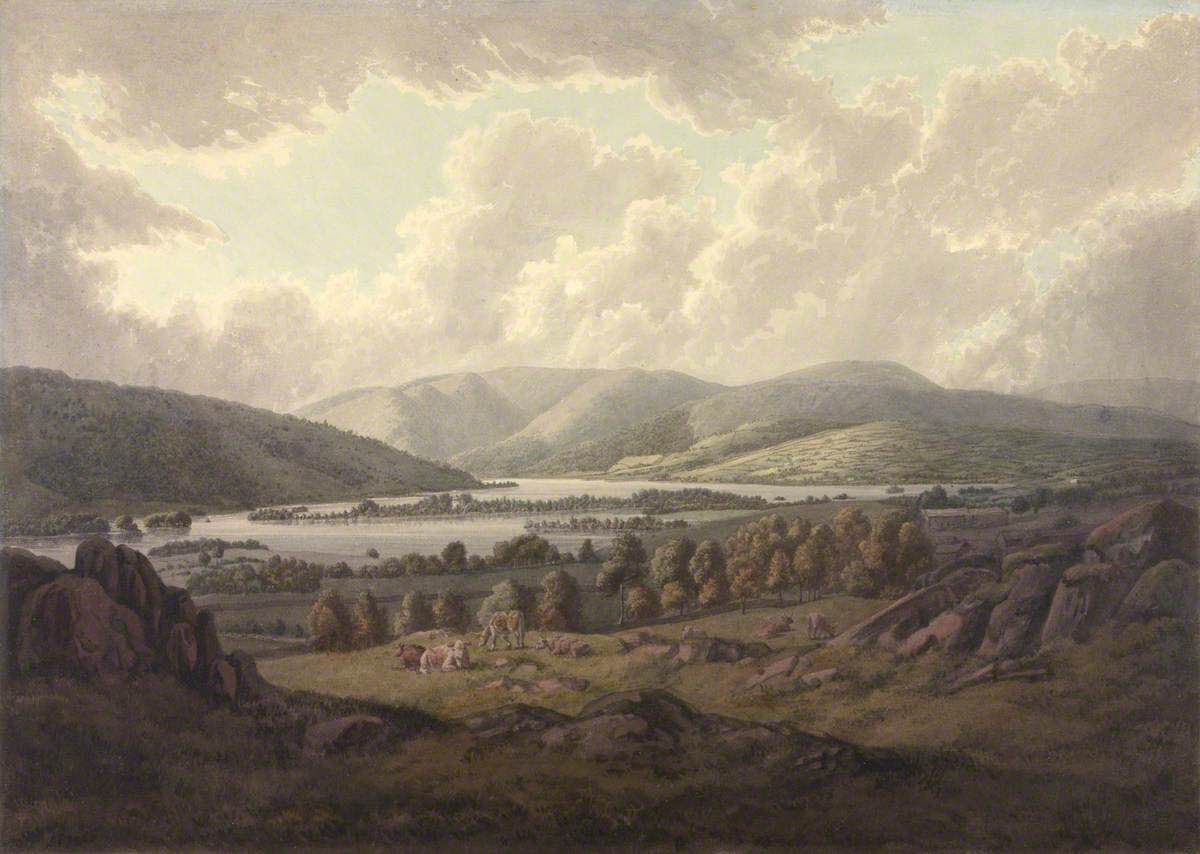

William Green (1760-1823), View of Windermere and Belle Isle, pencil and watercolour, Eton College