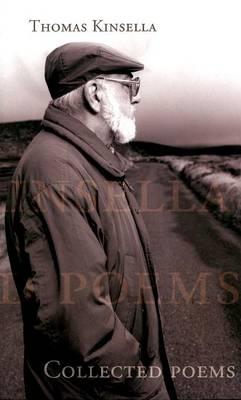

Thomas Kinsella (Wake Forest University Press, 2006)

Recommended by Trish Halligan

Thomas Kinsella (born 1928, Inchicore, Dublin) is a poet of the random and of restoration: ‘order’ is one of his most-used words, though he uses it in the sense of reconciliation rather than of restriction.

Kinsella came from a family of stone cutters and this inheritance somehow comes across in his writing: he puts shape to the stone but doesn’t always dress it. Similarly, his explorations of nature and his recollections of his native Dublin are neither bucolic nor nostalgic, and even more rarely are they consolatory. Kinsella often savagely satirises contemporary Dublin city planning, especially with reference to Ireland’s frequently catastrophic lack of conservation.

His other great recurring interest is the exploration of the physical similarities and differences across generations of his family. While his thoughts are often rooted in the sensuous and tactile (‘His Father’s Hands’, for example), he frequently describes hands which stroke, twist, clench and work, but which also touch to communicate when words fall short or as a silent assurance of trust. These poems are vivid fragments: they possess the quality of memories bursting upon the mind, like light cast into a room by a door suddenly thrown open.

Kinsella is not interested in tidiness or pat conclusions: there is rarely a sense of an ending in his work; even his later (much shorter) poems end by creating ripples of thoughts and evoke other times and places.