Social challenges in the healthcare system

Shifting demographics

It is no secret that the NHS is facing a myriad of challenges, including budgetary pressures and staffing shortages. Already, about 47% of trusts in 2018/2019 were operating in a deficit and external factors such as the Covid-19 pandemic are resulting in an extreme burden from outside – something which was not foreseen in forecasts. The focus of projections of cost are often on ‘bottom-up’ challenges, such as those that result from changing population demographics. One of the most important demographic changes is the ageing population. Due to improvements in nutrition and healthcare, people are living longer than ever. As of 2015, more than one in five of us was already over 60, and the number of people over 60 is expected to increase from 14.9 million in 2014 to 18.5 million in 2025 (ONS, 2015). As we get older, we also increase in the number of concurrent health conditions we tend to have. In 2012, 75% of 75 year olds in the UK had more than one long term condition, rising to 82% of 85 year olds (Barnett et al, 2012). The amount of people who are over-65 is only expected to increase as a proportion of the population. Twenty-five years ago the proportion of over 65s was 15.8% of the population, today, it is over 18%. The shifting demographic can be seen in the following projection from the ONS:

The impact of ageing

While one would intuitively assume that age itself is what drives increased healthcare expenditure, it is actually the case that one’s healthcare demand increases most as a result of being closer to death. One’s healthcare use generally peaks in the final year of life, and of course, this tends to be when most people are older. Nonetheless, this manifests in the following graph which depicts UK healthcare expenditure across the life-course:

No doubt you can envision how the combination of the changing demographic as well as the 5-10x healthcare cost increase that occurs when over the age of 70 will cause significant burden on the NHS and will require either significantly more investment in treatment and prevention, or changes in the way healthcare systems are costed, to be sustainable. Have a look at Public Health England’s full report on population change and trends in life expectancy for a deep dive into how the population has changed over time.

However, it is not only ageing that causes higher use of healthcare systems, a divide is also present across low and high education categories – but this is generally the case worldwide. The following figure from the OECD illustrates this:

This is perhaps due to factors such as smoking rates and obesity being drastically higher in those with lower rates of education. The following video outlines other socioeconomic and demographic contributors to health:

After watching the video, see if you can answer the QUIZ!

Other contributors

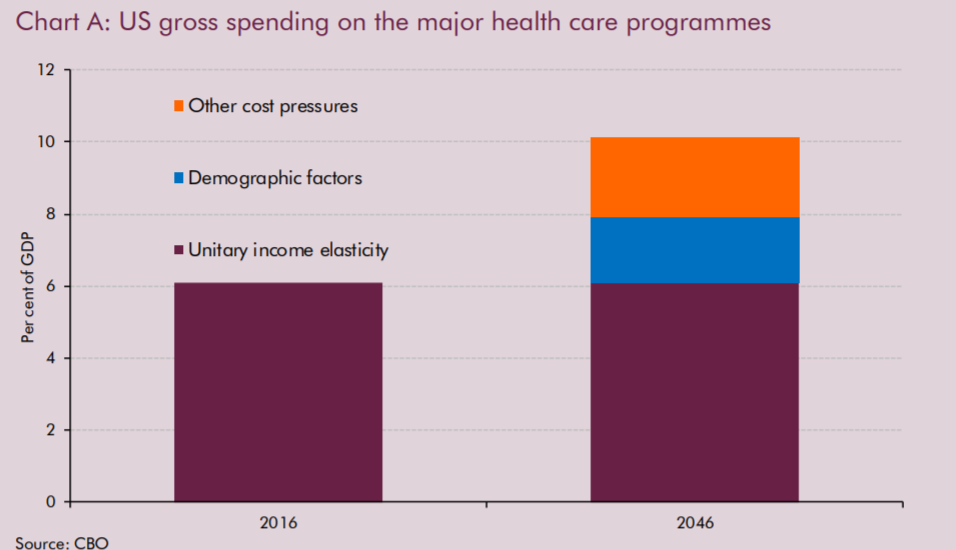

The OECD also points to other factors as key drivers for increasing healthcare costs, and even argues that these are more important than changes in demographic. They suggest that, between 1995 and 2009, most rises in healthcare expenditure could be attributed to rises in income rather than demographic effects. Likewise, the European Commission in 2013 identified that population ageing had a positive effect on healthcare spending growth, but that larger effects arose from changes in income and technology, the latter of which, while responsible for improved treatment, often comes with increased cost.

In the US, the projected increases in healthcare spending expected between 2016 and 2046 are approximately 60% ‘other cost pressures’ and 40% demographic:

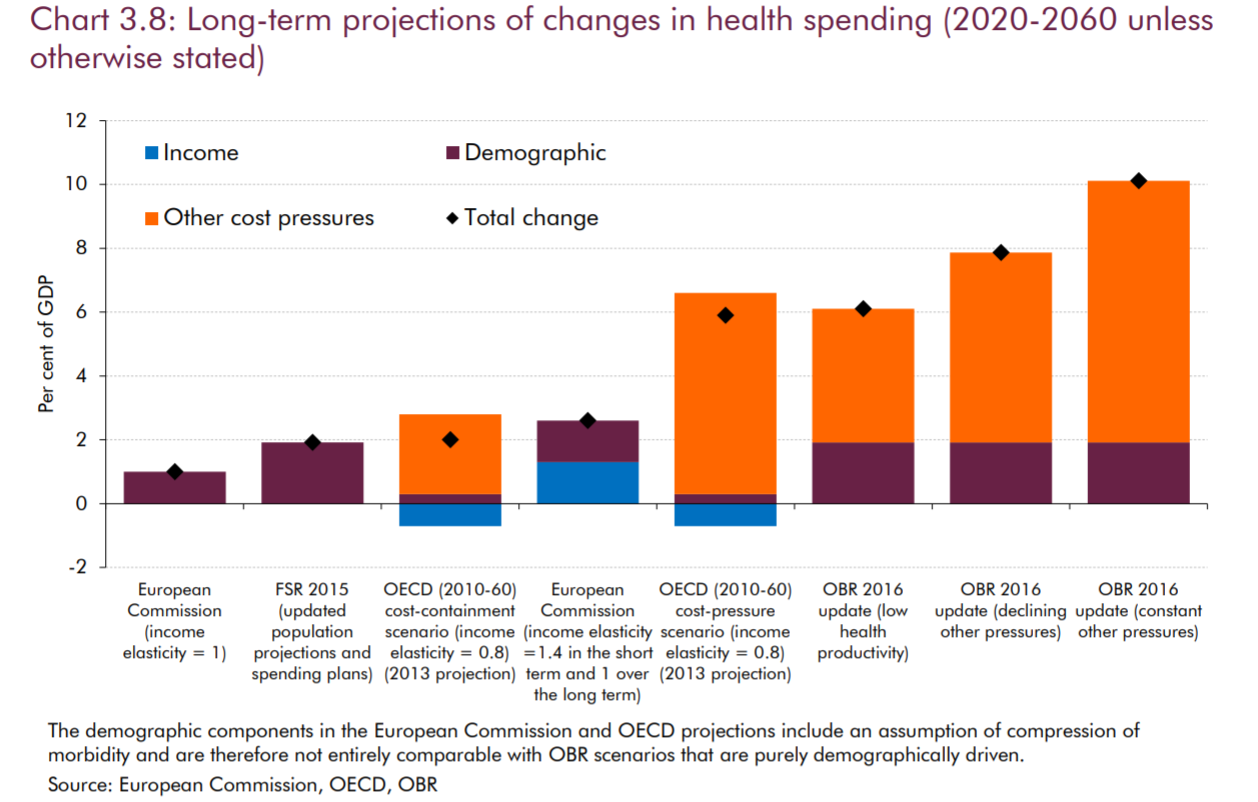

Nonetheless, regardless of cause, real concern remains about the increase in healthcare expenditure as a proportion of GDP. In 2018, the UK already spent almost 10% of its GDP on healthcare for its residents, which is slightly above the median for OECD countries. Various projects put the expected additional change in this metric to be significant, with likely estimates being a further rise of approximately 6-8% as a proportion of GDP – costs that will have to be recuperated in some manner:

The impact of external factors on healthcare spending

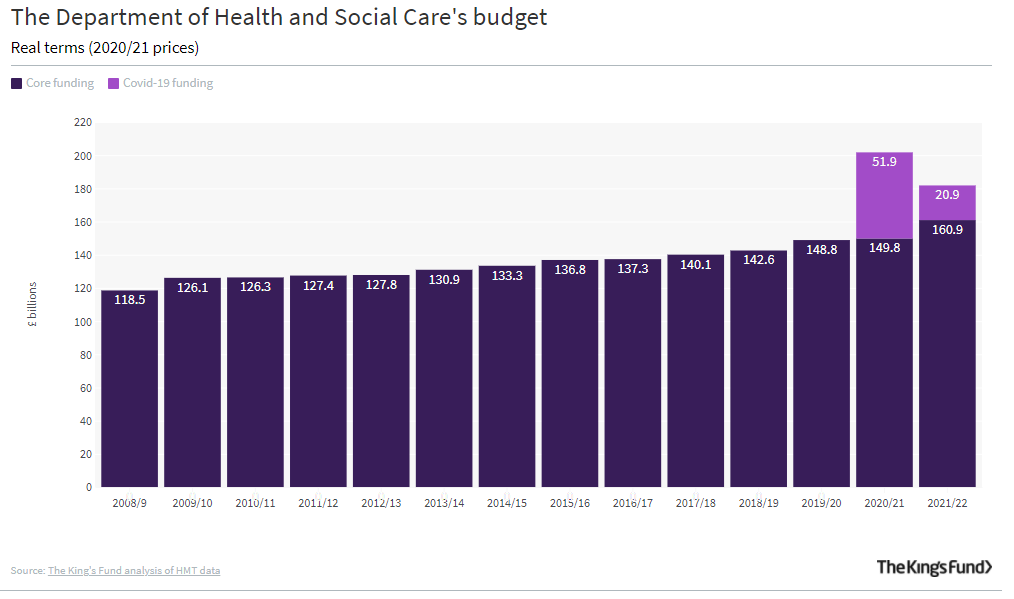

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has made an interesting ‘case study’ of what might happen to NHS spending as a result of short-term ‘shocks’ to the system. Of course, this operates outside of any changes to demographics, or technology, and rather pulls one’s attentions toward environmental hazards and external factors. Far ahead of what was expected, the overall impact of the pandemic has necessitated a 25% increase in funding for the year of 2020 in comparison to 2019, and this trend seems likely to continue into 2021. The impact of this can be seen in the following chart, and, combined with the shrink in GDP that occurred in 2020, has likely increased the NHS’ share of GDP spending to 13.1% of GDP already.

Please have a read of this article by the King’s Fund for a full appreciation of the funding impact of Covid-19.

Paths towards cost savings

One of the key focuses that is being proposed by the NHS Five Year Forward View and by moves towards population health based outcomes is that of prevention. One of the foremost examples of a programme focused on prevention of a major condition is the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme. Type 2 diabetes has such a focus because, in a typical year, in terms of treatment costs it accounts for around 9% of the annual NHS budget – or £8.8 billion per year – and type 2 diabetes is caused by poor lifestyle behaviours. In England there are 3.4 million people with type 2 diabetes and a potential 5 million more who could have it soon. Preventing progression of pre-diabetes to diabetes needing treatment will save significant cost and prevent significant disability. As type 2 diabetes is keenly linked to body composition and overweight, the prevention programme focuses on dietary advice, as well as physical activity and weight loss. Tomas et al. (2016) have analysed the potential economic impact of the programme if rolled out to high-risk adults 16 years or older. They found that there was a 97% probability of the programme costs being recouped after 12 years, with a return on investment of over £1.28 for each £1 invested. Likewise, significant improvements to quality-adjusted life years were identified, allowing people to live disability-free for longer.

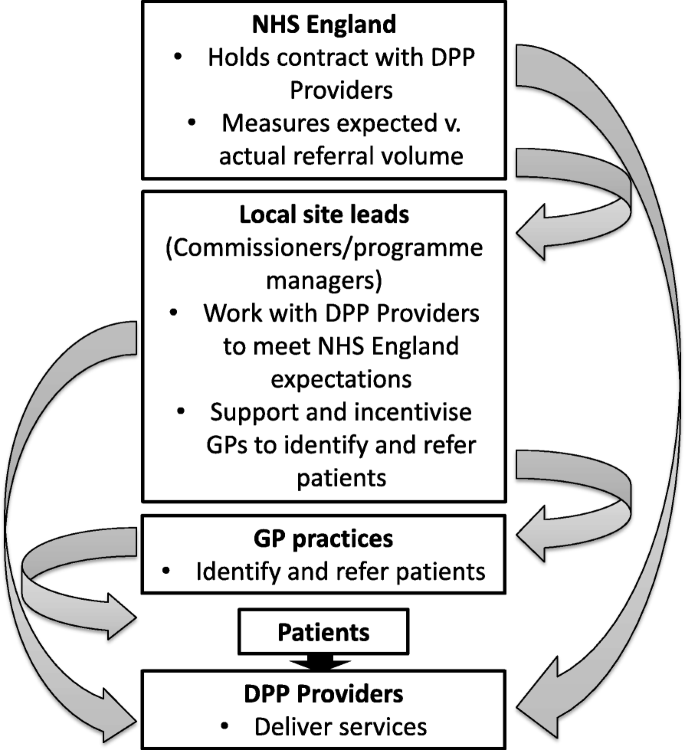

This programme was expected to be fully rolled out in 2020 across England and it will be interesting to follow the results over the next few years. Early lessons learned indicate that there are some issues in getting the programme rolled out efficiently across the UK, with a complex implementation pathway being partially to blame for this:

This manifested in a lack of clear roles and responsibilities between hierarchical actors and lack of communication, both of which were affecting rollout. The move to Primary Care Networks across England was also put forward as one way to address the issue of ‘buy-in’ by particular primary care providers.

Nonetheless, the analyses identify this programme as promising and likely to deliver important savings over a number of years. With the other top 4 diseases (ischemic heart disease, stroke, COPD, and lung cancer) underlying morbidity and mortality in the UK also being underlined by lifestyle behaviours, it is not impossible to imagine a scenario where more preventative programmes are rolled out with significant cost savings in tow.

What do you think needs to happen in the NHS to make it more sustainable?