Ra’s Dance, by William Bailey

2000 BC The First Solstice

The crowd of faces gathers around the stone megalith. They ripple in anticipation, producing indecipherable murmurs of joy and awe. On the horizon, a thin sliver of orange light is emerging over the muddy plane, the landscape now a quagmire beneath hundreds of scurrying feet; walking, hauling, working, settling. The site of the monument has become a hub of humanity, and a convergence point for people from across Britain. It represents the ability for society to come together for something beyond their own mortal interests. The blessing of agricultural development gave humanity freedom over their own destiny, and yet the solstice celebrates the one aspect of Earth which the human race cannot control. The first hour of the ceremony sees the sun rears its head, framing itself triumphantly behind the towering arches of the sarsen stone circle. In the distance, visible through the eastern arch of the outer ring, is the glorious silhouetted figure of the heel stone, standing in defiance against the awesome sunlight. The sun, now fully visible, is like a halo, positioned perfectly with the tip of the stone at its centre. “I peer through the stone looking-glass, and I can see my children. They do not understand me, and yet they can respect my beauty.”

The mass of excited people is still shrouded in darkness, with only the astonished faces of the front row being painted by the soft orange sunlight. The sole distinguishable character is the High Priest, standing between trilithons with his arms outstretched, adorned with some manner of ceremonial dress. His extravagant mannerisms and the zeal with which he flaunts a wooden staff makes clear that this isn’t his first solstice. And yet the congregation has no eyes for the Priest, only the benevolent idol in the sky, now rising high above the stone circle.

“To characterise Man’s actions as quaint would be underselling his devotion. His admiration for me is compelling, and yet that admiration is forged in fear. I am not benevolent insofar as they view me as their steward, but I am benevolent in my capacity to seed devastation. That is my role for humanity, and that is the role I am destined to play.”

2000 AD – The New Solstice

The world of the 21st century has become a hive of activity, bristling with life. The modern skyscrapers, bearing no resemblance to the clumsy clusters of huts in prehistoric Britain, are now reflecting the morning sunlight in the handsome façades of their glass carapaces. This is a society who has mastered fire and used it to burn the primordial fuel from which they descend. The towering silhouette of consumer capitalism is like scar on the landscape, extracting every last drop of resource from the earth and regurgitating great plumes of gaseous poison into the heavens. Humans are the undisputed victors in a game of their own design. “I look down upon the new world of my creation. The grass is like paper – fragile and fleeting. The concrete lining the streets of Man is equally so. I think of this world as a lonely satellite, turning its motion into energy, turning energy into life. Inside that bobbing sphere of atmosphere, Man feels protected for he is at home. His enclosed ecosystem constructs the illusion of self-sufficiency; a safety blanket shrouding him from the anxieties of the wider universe. I have watched him grow. In neolithic Britain, I was admired. In the Egyptian Kingdom, I was worshipped. The sun god Ra was a sacred deity – king of the gods and father of creation. While Man pretends to have renounced the old ways, his loyalties seldom fray from that of his forefathers. Man is predictable. I remain the pillar of civilisation: I grow his crops, I warm his oceans, I nurse his world into stable orbit around my glowing heart. But he is ungrateful. I have become the source of resentment. It has come to pass that the fruits of my generosity have fanned the flame of scorn, and the latest generation of Man blames me for his decline. They point at the melting glaciers and the burning forests, and they pass judgement on Ra; once the life-giver, now the scapegoat. How can a god who assumes the form of an inferno, showering Man with my lethal rays of hell, ever proclaim innocence? The jury has heard the case for the prosecution, and my silent dissent has fallen on deaf ears. Man is angry, and Man is vengeful. Had he not lit the atmosphere in a purge of industrial fury, one presumes my reputation may have stood in defiance against his scathing flagrancy. But alas, the universe forbids me to speculate the nature of destiny, and I must accept my role as an outcast to my own children.” — The rebirth of the solstice festival has begun. The celebration feels like nostalgia for a past that no one can remember. A procession of vehicles pulls into the carpark and pay their admission fees to English Heritage; admiration of nature has become a privilege, reserved for the well-travelled and wealthy observers. Beyond the carpark, the fractured remains of Stonehenge sit virtually untouched in their nest of English countryside, ignorant to the roads and electricity pylons which surround them, and entirely impervious to the perpetual flocks of tourists. At the site of the megalith, the sizeable congregation is much like that which populated Stonehenge 4000 years ago. There are druids, witches, naturalists, astronomers – many of whom are dressed in bastardised renditions of traditional robes and garments. The civilisation which roamed these lands is now shrouded in mystery and confusion, leaving any remaining morsels of culture to occupy the domain of speculative archaeology. The celebration of the solstice is a revival of its predecessor in name only, and the religious and spiritual traditions of prehistoric Wiltshire will forever be lost to time. Yet despite this, the solstice reignites something dormant in its occupants. As the hundreds of eyes stare at the brilliant orange sun rising over the heel stone, even the flickering wall of smartphones cannot diminish the ancestral connection which takes hold of the audience. That sense of cosmic dread felt by the neolithic settlers is now written unmistakably on the faces of their descendants.

“In the age of enlightened humanity, I remain a symbol of permanence. When a rational human looks me in the eyes, he can perceive nothing except billions of fusing hydrogen atoms, releasing insurmountable quantities of energy and bathing my image in brilliant a sea of divine light. Yet, to the human spirit, I represent something more. I am security. I was here long before life blossomed in the primordial oceans of Proterozoic Earth, and I will be here for long after its inevitable demise. I will outlive everything on this planet, and I will outlive whatever replaces it. To me, this is not sad. Nature is such that all things end.”

6000 AD The Last Solstice

The spark of humanity is a distant memory. In the years since uncovering the climate crisis, humanity blindly led itself into a downwards spiral of destruction and chaos. As the situation worsened there was mass migration, followed by famine, followed by war. Over time, the human race tore apart under the weight of its own burdens. The British Isles was abandoned long before the birth of the last man, left as a desolate museum for the eternity which is yet to follow. “Man never gave himself the chance to change his own destiny. This is the apocalypse he built for himself, and not once did he question it. The human race was so determined to fight an invisible enemy that it never saw the honour in unity. Whether it was kingdoms or empires or nation-states, Man was defined by his self-destructive desire for fragmentation – the desire to win. “This is not the failure of capitalism or the failure of democracy; this is the failure of human nature.” Somewhere on the green plateau of Sailsbury Plain is the crumbling legacy of a forgotten monument – the last reminder that an intelligent species walked these lands. The central circle of trilithons has sunk and shifted, the product of vandalism and disrepair; the horizontal stones which once topped the almighty horseshoe have long since slid into the depths of the hungry earth. The only remaining glimmer of familiarity is the four-legged frame of the sarsen remains, which aligns the outer circle with the distant heel stone in the east – despite years of neglect, the structure is remarkably still adorned with its trio of connecting lintels. The weary megalith is as alien to this empty world as it was when it was first hauled here 8000 years ago. On the dawn of the solstice, the sunrise is indistinguishable from its neolithic predecessor. The lack of humanity in this vast and lonely countryside feels almost immaterial to the predictable beauty of the sun-bleached landscape. As the heavenly orange light rises proudly above Stonehenge, one might imagine a mournful Ra, the ancient Egyptian sun god, surveying his desolate dominion and saying his final goodbye to humanity.

“Man liked to believe he was impervious to nature. In the tales of the Old Kingdom, men and women formed from the droplets of my falling tears. The reality is much more beautiful: my tears are the makeup of the solar system. I watch hurtling celestial bodies rise from the dust of supernovas and collide with incomprehensible magnitude; I watch the seeds of life blossom and fade away like breath on a mirror; I watch the vast planetary oceans boil into a cloud of tumbling vapour, only to reform over a thousand millennia. As I cry, the universe keeps turning. My tears fall not just on earth, but the entire solar system over which I preside. Man is just a footnote amidst my billion-year dance with the stars.”

‘Ra’s Final Goodbye’ – Illustration, by William Bailey

A Journey Through the Peaks by Khalil Dajani

Part 1: Waldeinsamkeit

Our journey began as a way to waste time, procrastinating from our GCSE’s, nothing seemed bigger or more ominous. The studies started really wearing us down, constant revision reading about who cares what, ‘its pointless useless information’ I recall thinking to myself. “Take yourself on a walk, go with your friends” my mum suggested. ‘Ok’, I thought, ‘a way to do nothing with my friends, suggested by a parent… perfect’. I called up my friends and around thirty minutes later we met up at the bus stop we normally do. The cars whizzing past us, we start walking “into nature” no destination or navigation, just a knowledge that the Peak District “is over there somewhere”. As we walk, we start escaping the houses, the clutter of bins, traffic lights and pavements opting, to follow the desire lines of previous explorers. We meandered away from Sheffield’s brimming streets toward the open arms of the Peak District. The air starts to feel fresher its quieter, the whizzing of the cars displaced by the rustling symphony of the wind flowing through the foliage.

We walk uphill for hours until we reach a plateau, only then do we realise where we were and what we had. We looked upon the view, the heather-clad moors rolled like a purple ocean the waves frozen in time, ancient rocks stood sentinel over the evergreen fields. The moors were rich with the smell of wild thyme and lilies. The Earth was demonstrating its eons, we stood in transient witness to its grandeur and prowess. As we walked, we considered all of those who had walked upon this land in the past, a reminder that the environment isn’t simply a backdrop to our lives but an essential living breathing entity that demands our respect and concern. We found a bench hidden in the hills, facing the expanse. The bench seemed as much a part of the landscape as the boulders and grass, and as did we, sitting there we felt a sense of belonging. This bench, this view, this was our chapel in the wind. Our alter to the sublimity of nature. We sat there for hours discussing the creation of this beauty, taking in that the rolling hills are a testament to millennia of development and undisturbed becoming. The city and our academic stresses were overshadowed by the grandeur of where we were with the sporadic hum of passing cars feeling like an echo from another world. It was a fleeting reminder of reality in our newly discovered dream world. We started noticing the sheep, the sheer number of them dotted around the contours of the land with an unhurried elegance, their presence stood as a stark contrast to the cars rushing to get who knows where. The harmony between the grazing sheep and vast heath demonstrated natures coexistence, a reminder of the intricacies of biodiversity, leading us to consider our role in acting as stewards for such beautiful places. We began feeling the essence of waldeinsamkeit, not from feeling alone, but from the connection we felt with nature. The realisation of how small we are or to put it better, how big the world was, the sense we are part of something bigger than we can imagine. As the sun started dipping under the hills, the shadows cast danced with the fading day, as the light started leaving as did our stresses, the societal pressure and impending exams felt manageable and small. The stress subsided with a sense of understanding and love of life and the world replacing it. The ominous fear of the real world dissipated with the knowledge we are merely a footnote in the eternal symphony of Earth. This bench became a home away from home, our place where the essence of our youth met the wisdom of the land. We left feeling small and insignificant, but this feeling was moreish and freeing, we felt liberated and free. The world felt

limitless and awe-inspiring, we felt like we belonged.

Chapter 2: Wanderlust

Time marched on and were now on the cusp of adulthood stood on the precipice of freedom. Finished with school a chapter has closed, University and impending adulthood loomed on the horizon, but before this our summer holiday. Weeks of doing nothing with no one to answer to and nothing to answer for. Our days became a flurry into our wanderlust, exploring every nook and cranny the Peak District had to offer. No longer marching on foot, we had the keys to our mobility, a car that hummed with the promise of discovery. We were pilgrims of the sublime, now being able to see more than ever and sought the zenith of nature’s grandeur, an immaculate amphitheatre to witness the wilderness of the Peak District. We drove down winding roads etched into the hills looking out at the landscape searching for the perfect place to sit unwind and adore the beauty of nature surrounding us. To one side we saw stone cliffs that rose out of the ground like ancient titan’s faces inscribed with the wisdom of the Earth, to the other the bloom of heather, purple as far as one could see. A tapestry of different shades, violet, mauve, and heliotrope laid out like a carpet the land has places for all the creatures of the world to enjoy. We drove through the trees unrushed, taking in the sights before we found a spot to settle. We stood atop a sun laden promontory of sandstone and fern which must have watched the turning of ages in stoic silence.

We took a few minutes to take in where we were, a yet to be discovered domain, yet still part of the ever so familiar Peak District. We began walking, our boots crunching on the gravel and soil, our steps stirring the fragrance of the land wafting up to us every step we took. We walked through the overgrown wild grass, traversing boulders, even though we had never been here it still felt like home. The waldeinsamkeit of our earlier expeditions still prevalent but overcome by our wanderlust, discovery was our mission it’s all we desired, and nature provided. Finding our way to the cliff edge we sat, legs swinging over eternity sat on a cliff that had been in development for megayears all for us to sit upon. The vast valleys sprawled in front of us a living breathing mosaic, we found ourselves ensconced in the magnificence of nature. We no longer felt as small and insignificant, we were older, braver, we felt like adults. Nature still felt overwhelming, but we felt ready for it, it was no longer intimidating it was ours to explore and search for. The cliffs that surrounded us felt as large as our ambitions, the difference being our ambitions were not grounded in the earth but poised to take flight on the zephyrs that enveloped us. The feeling of ownership came over us, this is our Earth, it reinforced our ethics wanting to protect the sanctuary we found ourselves part of. As the sun set we took it all in for a final time, not knowing when we would get back here, if we would all remain friends so many unknowns flowed through us. Yet we found comfort and reassurance in nature, the enduring cliffs and rolling moors stood the test of eons, their beauty unyielding. The Earth would remain the same, a testament to time’s passage, we hoped our friendships would mirror the landscape, everchanging but always there. A home away from home we can always return to. We pledged there and then to never lose the wanderlust we have in our hearts and carry it forward to everything we face. Holding sacred the natural sanctuaries that had offered us a sense of belonging, solace and inspiration. As we drove back through the twilight the road serving as a link between the realms of human haste and the purity of nature, our quest to find the nicest areas of the peak district transcended this. We found a place to call our own, purpose and commitment to cherish and safeguard the environment we loved. This was our initiation, not into adulthood but to a lifelong love of the environment which bound us all, tasked with protecting, and revering the wild which had imprinted itself indelibly upon our souls.

Chapter 3: Heimat

Winter cloaked the Peaks, the vibrant purples and greens of our previous visit now replaced by a silvery frost, the heather’s glorious purple laying dormant beneath ice’s delicate etching. The stillness of the Peak District acted as a counterpoint to what had been a crazy few months at university. University, which had spread us across the country, but winter brought us back, all seeking a Christmas dinner cooked by Mum and presents. Being home also meant a reunion to our bench, our base. We sat on the cold bench, bums cold, breath visible in the crisp air, no birds tweeting or cars driving. The air was sharp with the smell of cold stone and dormant earth. It was almost pure silence, contrasting the warm chorus of our muttering and laughter, exchanging stories of the eventful past few months. We felt comforted by our surroundings, the hills, and cliffs nothing had changed, it was as we left it. Nature dressed in its winter garb was the quiet friend at the reunion listening to our tales hesitant to share what it had seen. The moors were devoid of sheep or any life, it lay quiet under a layer of frost the occasional crunch of frozen land beneath our feet served the soundtrack to our reunion. We sat for hours; the cold had no impact on us, warmed by the spirit of comradery with no one wanting to leave the comfort of the place. Our conversation meandered like the roads around us, but we felt like we belonged, a feeling hard to come by at university, our wanderlust had subdued over the months away from home. All we wanted was this, this comfort, our heimat to simply sit in a familiar location viewing the unchanged sights and hearing the voices of those we love the most. The nature around us seemed to mirror our own journeys, though slightly different in appearance, it remained at its core unchanged still there for us, offering us a place to go. The bench once symbolised escape and discovery had become a beacon of return and reflection. We used to view this bench as a far away place we could run to; it was exciting and scary; the views were overwhelming the grandeur of where we are used to take over us leaving us speechless. Now the same bench was comforting, nature was a friend I wanted to visit as opposed to an awe-inspiring giant I wanted to explore and uncover. The bench hadn’t changed, the nature was as it ever was, the ancient rocks remained unmoved the cliffs ever presence, but we had changed, our relationship with where were had changed. As we sat chatting, we began thinking about all the times we had sat there and laughed, cried, argued and smoked, the sense this place had transcended and changed overcame us. As the light began to fade and the winter sun dipped behind the hills casting long shadows. We had a realisation, our adventures and lessons we had learned hadn’t impacted our connection to this place, it had strengthened it. The land was unjudging, it was an ever presence we could go to amid the whirlwind of our lives. The icy cold view also served a poignant reminder that no matter how long winter felt, the heather would bloom once more lighting up the sights with majestic purple, akin to our friendships which would blossom upon reunion. As we got up to part ways once more the understanding that this view, this bench, it’s a friend, it’s been here for us and always will be, we didn’t want to leave, but we knew we would return. This was our place, and we won’t ever let it go.

Dreaming of an Oasis, by Emilia Mathias

Straight roads and desert as far as you can see. Mountainous terrain, cracked land, dust, lonesome cacti, derelict hamlets. I know what I see now will soon change, it will be replaced by cool green tones, the heart of an oasis in the midst of the desert. The glossy car we rented just a short hour ago, now embodies the appearance of the harsh terrain, as sand and dust cover its cherry red paint. It has been ten years since I last went home. Looking out of the car window, my eyes heavy from travel, begin to flutter to a close, and as they do, the harsh desert slips away.

Warmth feels my cheeks, and a mosaic of colours cascades through the trees, as crepuscular rays of emerald, lavender, teal, magenta and gold flash through my gaze. A little girl in the distance laughs and playfully waves, and with each step she takes her flamenco dress sways. Jewel like petals cascade down her dress, the ruffles of her sleeves are adorned with lantana flowers of vibrant pinks, oranges, and yellows. Blue bells hang from the hem of her skirt, and around her waist, delicate verdant leaves intertwine. Swallows dance around her and many more of nature’s creatures like bees and butterflies follow her delicate little steps. As she gets further away, I am overcome with the feeling that I must follow her. She leads me down a rugged and dusty trail, where a familiar and homely soft smell of herbs, spices, lavender, and jasmine dance in the air, warmly embracing me. In the corner of my eye, a cafe nestles in the lushness of an untamed grapevine. Its open plan is full of mismatched cushions, rugs, hammocks, and Moroccan lights and lanterns, all adorned with intricate patterns and vibrant designs slightly dulled by the harshness of the sun. The people in the cafe turn, and I do not get a warm smile in return. Their eyes seem heavy, sad, and full of sorrow.

As I grapple with understanding their emotions, the little girl is off again. She dances and gracefully manoeuvres, and with every step we take, the path becomes more untamed. Each glance I take seems to be more beautiful than the next. We are no longer on the dusty, sandy trail we started on. Instead, the meadows have become taller, and the ground carpeted with wildflowers and soft grass. Around us, pink-blush almond blossoms fall gracefully like feathers, leaving sweet notes of honey as they pirouette through the air and palm trees rustle, towering over, providing sanctuary from the beating sun, as rays of sunshine slip through the green foliage, creating a canopy of warm greens and yellows. Alongside the trail, the comforting sound of water trickles and cascades over smooth stones, seemingly whispering harmonious directions to the girl through the increasingly wild paths we traverse.

We reach a small opening in the lush, deep green corridor and looking through it, there is a field resembling an abandoned allotment. Rows of withered plants droop, wilted tomatoes hang to their vines, an olive tree seems to be the only thing that thrives, the soil is cracked, and weeds have crept into empty flower beds. A group of people are displaced around the barren land. One man relentlessly pounds into the dry earth with an old wooden garden hoe, as sweat drips down his face, and another seems to be in disbelief, pacing up and down the dry contours of mud and soil that outline the deserted allotment. The girl carries on walking, seemingly oblivious I have fallen behind, as I gaze in disbelief at the dissolute scene in front of me. Scared I will lose her, I draw my eyes away.

The velocity and ferociousness of the stream we have been following increases with power as we continue to walk. The air becomes cooler, tangled with the smell of moisture and earth. We walk through a giant crystal formation, made of two gypsum crystal boulders fallen perfectly, creating a tunnel of geological jewels. We walk in darkness, the sound of the water guiding us.

As light creeps in at the end of the tunnel, the pounding sound of water gets louder, it resonates deep within me, harmonising with my body’s internal rhythm. The crystal tunnel opens up, and I stop in awe. Water cascades down the side of a green rugged mountain, and eventually, after plummeting great heights, the water falls into a pool below. The water churns and swirls into deep blue circles, as the sun shimmers on the water creating an image resembling Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night painting.

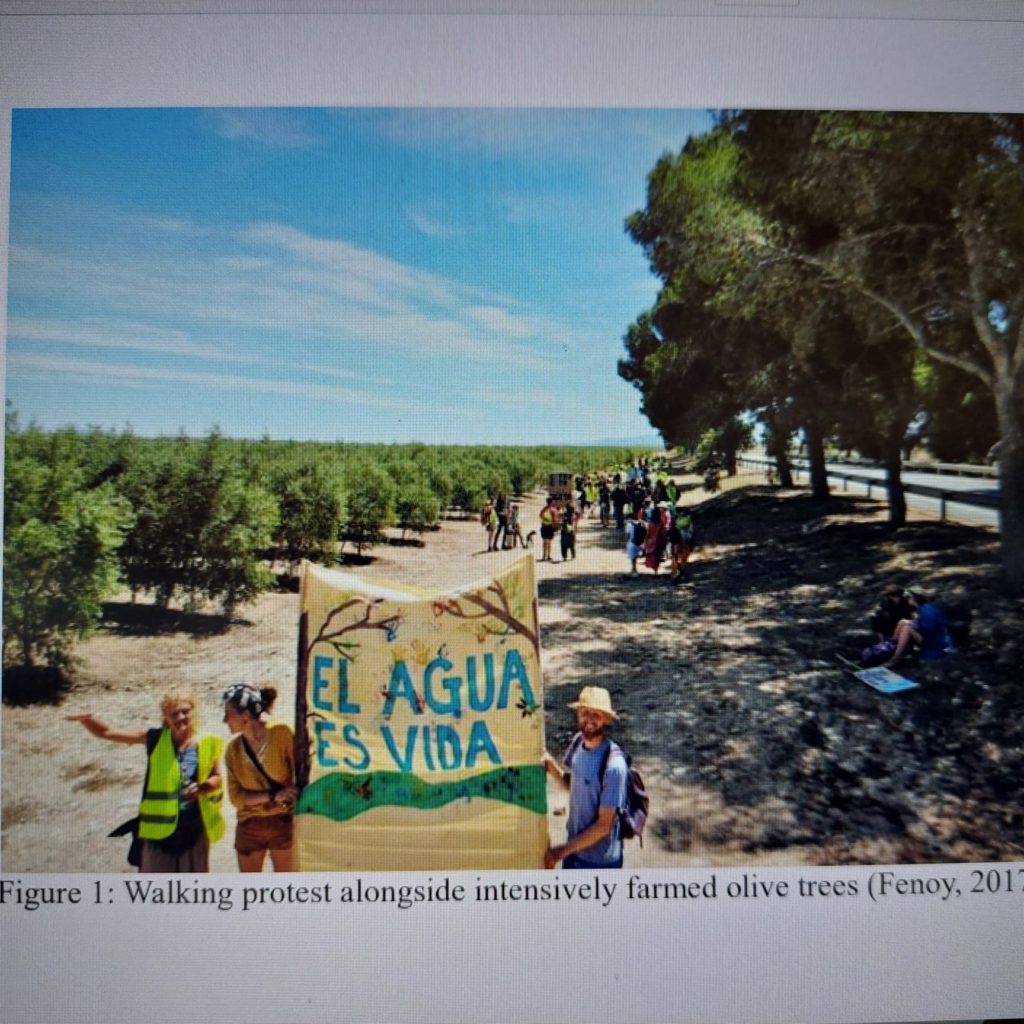

Looking to the side, I expect to see the girl has moved on. To my surprise, she sits at the water’s edge, as turtles dance around her little toes and dragonflies hover over the top of her head. Her head hangs low, and when she looks up her brown eyes are filled with tears. I whisper, asking the girl why she is upset. She ignores me and her smile drops. I gently push, questions flowing out with every breath. Such as why those in the cafe looked so sad and how could the allotment be so barren in this land so clearly abundant in water. Taken aback, she stands up, a tear slipping down the side of her face, she slowly raises her small index finger, and I carefully follow, as she points past the waterfall, to an opening of land on one of the neighbouring mountain edges. As far as my eye can see, homogenous lines of trees plaster the land, with rows of olive trees uniformly planted. The girl’s gaze drops again, her finger trembling as she lowers it to her small frame. She begins to move once more, and I hastily follow. This time she runs with speed, as tears flow down her cheeks. My heart burns as the militant trees flash through my eyes, in stark contrast to the natural diversity surrounding us, leaving a rock in the bottom of my stomach. I carry on following the girl, however, it seems we are no longer following the sound of water as we traverse up behind the side of the waterfall and our run turns to a scramble. Eventually, we boulder closer to the top of the mountain. The gushing sound of water is still present but silenced by what can only be described as the sound of heavy, metallic machinery pounding into the Earth. As we reach the summit, the mechanical sound sends shivers down my spine and my skin prickles in fear of what I am about to see.

The scene at the top of the mountain brings me to my knees, as tears flood from my eyes, much like those of the little girl. Steel and black plastic pipes as far as the eye can see, massive holes have been drilled into the ground and pumps appear to be savagely extracting water out of the ground. I have a million questions and emotions racing through my mind, but as I turn to face the girl, her luminous complexion has gone. She looks fragile and pale, her eyes sunken, her skin dry, and her lips cracked. The flowers on her flamenco dress have also begun to welt and shrink away, leaving her once vibrant clothing, dull and in disrepair. The creatures which harmoniously danced around her, also look to be fading away, and as the girl stands still, her skin starts to crumble, rapidly dissolving into grains of sand, and within seconds a mound of dust is left behind.

“Darling, wake up, we are here!” With a gasp, I jolt upright. My heart pounds heavily against my chest. I rub my clammy hands down the side of my cold leg from the car’s crisp air. I try to catch my breath, and as I shake my head, I am thankful it was all a dream. The car comes to a halt, parking in the sanctuary of shade provided by a withered old fig tree. Opening the door, I am instantly greeted by the hot late spring air. I know as we begin the trek down to the oasis the air will become perfectly refreshed, almost as if somebody had precisely calculated the amount of water particles that should be laced into the air to bring the perfect cooling comfort on a hot day. I swing my legs to the side of my seat, and they shake from the adrenaline that remains in my body. Pulling myself out of the car, I see the hippy cafe in the distance, effortlessly sunken into the breath[1]taking backdrop of the untamed grapevine that embraces it as its own. The closer I get to the cafe, which lies in the quirky little hamlet just before the depths of the oasis, the more I feel at home. I love this place. The houses in the hamlet are all quirky and unique, some have bright blue doors, painted the kind of deep blue that makes you think of charming and quaint Greek fishing villages, whereas others have opted for painting murals of the sun and stars, and in the centre of it all, the cafe. It has an enchanting aroma, filled with traditional vibrant Moroccan textiles and decorations such as mismatched cushions, rugs, and beautiful delicate lanterns. You can usually find one of the locals here, cooking freshly prepared fruits, herbs, and vegetables from the communal allotment. The smells that float out of that place, create a welcoming and embracing feel like no other. Somedays it might be mint, cumin, or oregano, and other days fresh garlic, or more zesty smells like freshly squeezed oranges or hints of lemon. However, today the homely smells do not embrace me, and the dust beneath my feet has not changed colour, by now the sand and dust have normally turned to a muddier consistency, as water from the oasis seeps into the land. As we approach the cafe, an uneasy feeling sets in my stomach. Its exterior, once painted with beautiful murals and intricate mosaic patterns, bears weathered paint and cracked tiles. The outdoor lounge is filled with overturned tables and chairs.

The thought that my dream might have not just been a dream makes my heart race again. My hands feel sweaty, and all the blood in my body seems to have rushed to my feet. I get an overwhelming desire to run to the waterfall deep in the oasis, the place where water first enters our sanctuary in the harsh and barren terrain. I run and I keep running, retracing the path I took with the little girl. However, this time I run alone, and the stream that normally flows alongside the wild path is gone. The once lush green tunnel of trees, verdant bushes, and flowers is sparse and sombre. Palm trees that once stood proud reaching towards the sky droop. The once vibrant flowers hang limp and thirsty, and bushes that lined the path are bear and shrivelled. The gorgeous almond trees normally in bloom weep, the carpet of soft grass that normally soothes my bare feet, as I Earth myself closer to nature, is now dusty, cracked and barren. I continue running, approaching the glistening tunnel formed of gypsum crystals, the gateway to the waterfall, which we could have easily been denied access to if two gigantic slabs of stone had not perfectly fallen some thousands of years ago. Finally, out of the tunnel, I gaze upwards, wishing to see water gushing down the mountain, but instead a sheer rock face greets me. The once thriving ecosystem is desolate. Trees and branches reach out like desperate limbs in search of moisture towards the bottom of the mountain where water once plunged and swirled. Fish, turtles, and insects desiccate and decompose in the piercing sun. I stand still, unable to process the scene in front of me. A high-pitched piercing sound fills my ears, like the one heard in movies after an explosion. As the sound of shock gradually fades it is replaced by a mechanical pounding sound of the Earth. I look as far as I can see to the top of the mountain, and as I do, pure horror, sadness and grief encompass me. The scene is exactly like my dream, and I feel lost even though I am home. Feeling weak from the shock, I cave into the force of gravity, dropping to the floor and hugging my knees, I want to be comforted and embraced by verdant trees, plants, and the sound of gushing streams.

NATURE AND ITS ROLE IN THE FORMATION OF MY (ENVIRONMENTAL AND NATIONAL)

IDENTITY THROUGHOUT MY LIFE By Barbora Rapantova

Hrdza (2021): Slovensko moje, otčina moja [My Slovakia, my homeland]

My Slovakia, my homeland, you are as beautiful as paradise,

The splendour dominates on your hills, the grove rustles in your valley,

Where our fathers worked, they sang in your fields,

My Slovakia, my homeland, you are as beautiful as paradise.

I have a homeland, the only one in the world where I play happily,

I love it, I wish it happiness and I will give my heart to it,

Here mountains and streams murmur, Váh1 sings beautifully to their tune,

My Slovakia, my homeland, you are as beautiful as paradise.

For me, this Slovak song celebrates and embodies the profound bond that Slovaks share with our country’s nature. Defining the link between humans and nature is not an easy task. On one hand, definitions often draw a line between nature and humans as if they were two distinct things. For instance, The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (2006) characterises nature as “the phenomena of the physical world collectively, including plants, animals, the landscape, and other features and products of the earth, as opposed to humans or human creations…” On the other hand, numerous scholars have argued that humans are not detached from nature and are part of it (e.g., Callicott, 1992, p.18). I would like to extend this viewpoint even further. Not only are we integral components of nature, but nature itself is part of us and constitutes an essential aspect of our identity. I have always regarded nature as something precious that we are all connected to in one way or another. Nevertheless, the Environmental Politics module pushed me to look at nature and the way it is part of me in a completely different way. I came to realise the pivotal role that nature has played in the formation of my identity. By sharing my experience, I wish to reflect on three things. Firstly, I would like to highlight how growing up in Slovakia fostered my relationship with nature and formed my environmental identity. Secondly, I would like to discuss that nature and culture are not two distinct phenomena and that nature has actually affected Slovak identity through its depiction in art. Finally, I will talk about how nature has contributed to my sense of national identity and is one of the reasons why I feel proud to be Slovak. Not only did my country of origin shape my relationship with nature but vice versa nature has shaped my national identity.

When I was a child…

… I spent every day with nature. Whether it was playing with my sister in the garden, going to the park, or a family trip to the mountains, the majority of my childhood was happening in nature. Because I lived in a very small village, nature was within a very easy reach to me. I remember how happy I was observing butterflies with my dad when they flew into our garden to feed on the flower nectar. Or when I woke up in December and I saw the first snow of the year. Or when I was watching deer and wild boars with binoculars from my aunt’s garden as her house stood right at the border of a hill. Nature brought me happiness. Back then, I did not realise how lucky I was to live in Slovakia. I did not realise that many children of my age did not have the opportunity to experience nature in such an authentic and easy way as I did. I did not realise how much these experiences were forming me as a person. …my parents used to read Slovak tales to me. My favourite of all Slovak children’s stories was “About Twelve Months”. The story taught me how important it is to respect nature. Maruška lived with her evil stepmother and stepsister Holena who, in order to get rid of her, sent her to the forest to bring violets in the middle of winter. After having wandered in the forest for hours with no success as everything was covered by snow, she saw a little light in the distance and decided to follow it. Freezing and desperate she came to a group of twelve men sitting around a fire. These twelve men were the twelve months of the year and represented the cycle of nature. They asked Maruška what she was doing there in the middle of winter. When she politely asked them for help with looking for violets, Month April melted snow next to him and let violets grow there. When she brought those violets back home, her stepsister and stepmother could not believe she had succeeded and sent her to the forest again to bring strawberries and apples. Both times she politely asked the twelve months and they helped her. After that, her stepsister Holena decided to go to the forest herself to bring more apples. However, when she reached the twelve months instead of politely asking for help, she told them to mind their own business. Because of her disrespect instead of helping her, they sent her into a snowstorm and she got lost forever (Dobšinský, 1880-1883).

My childhood was the period of my life when my environmental identity started to form. Clayton (2003,p.45-46) defines environmental identity as “a sense of connection to some part of the nonhuman natural environment, based on history, emotional attachment, and/or similarity, that affects the ways in which we perceive and act toward the world.” Even though academia often refers to identity as something that is constructed through social rules, practices, institutions and interactions (Brace, 2003, p.122), Clayton (2003, p.45) argues that our “connections to specific natural objects, such as pets, trees, mountain formations, or particular geographic locations” are just as important and need to be considered in the study of identity. In other words, environmental identity is the belief that one’s connection to the natural world constitutes a significant aspect of one’s sense of self (Clayton, 2003, p.46). The cultivation of environmental identity and the deepening bond with nature are correlated with the amount of time spent in the natural environment (Schultz and Tabanico, 2007; Tam, 2013). Especially in childhood, close interactions with nature have a crucial impact on the development of one’s identity (Kellert, 2002). I believe that because I had a childhood filled with time spent in natural surroundings, nature became an important part of who I am. Living in a small village also made a big difference as it provided me with more contact with nature that had not been (re)constructed by humans. For instance, Bunting and Cousins (1985) found that children growing up in rural areas tend to have a stronger and more positive bond with nature compared to those raised in urban settings. Furthermore, the stories my parents used to read to me added to my positive relationship with nature as books on topics of nature lead kids to have a higher appreciation of nature and the environment (EcoHappiness Project, 2022). I am not sure why I liked the story “About Twelve Months” so much but it taught me that if you behave politely and with respect towards nature, it will help you and provide what you need. Thus, nature played a crucial role in the construction of who I am now. While my childhood experiences formed the relationship I have towards the environment today, my understanding of nature and its important role in my life met with a new perspective when I became a student. Nature was no longer only a space of happiness but it became a subject of study.

When I was a student at primary school…

…one of my subjects was dedicated to nature and the way we should treat it. Of course, we had to study biology as everyone else where we learnt all the scientific phenomena surrounding the topic of nature. However, our primary school offered another course, which I don’t think many countries have. It was called “World of Nature”. Once a week our teacher took us outside and we dedicated one hour to learning about how to behave in nature so that it can prosper even with human actions affecting it. We learnt how to handle plants, how to act in the forest, how to take care of trees and we occasionally went out to pick the trash around the village. Back then I saw it as a subject that I didn’t need to do any homework for. It was just an easy relaxing lesson in between all the other more “useful” courses. Looking back at it now, I realise that this was one of the most useful subjects I had in primary school. I hardly remember what our biology teacher taught us but I remember that we need to take care of nature the way it takes care of us until today.

When I was a student in high school…

…I started realising how important nature is for Slovaks as a nation and how much it means to us. I saw this most in our literature. Especially, in the romantic literature of the 19th century, authors used to describe the beauty of Slovak nature and its natural landscapes in order to awaken the nation to stand up for themselves. Nature and our natural landmarks were illustrated as something precious worth fighting for. As Slovakia was invaded and ruled by many foreign nations throughout history, this was an important topic in our literature. Moreover, nature didn’t only serve as a means to awaken the feeling of patriotism and

motivate Slovaks to fight for their homeland and freedom, but it was used to compare characteristics of Slovak nature to characteristics of Slovaks. Oftentimes, Slovak women were compared to the beauty of nature and men were compared to its strength. One of the most important Slovak poems is called “Mor ho!” (Chalupka, 1868). We studied this poem multiple times throughout our studies and we even learnt some parts by heart – I still remember them today. The main thought of this piece of poetry is to encourage Slovaks to fight for the freedom of the nation. The writer names various characteristics of Slovakia and its

inhabitants that are worth fighting for – one of them being nature and natural landscapes:

Samo Chalupka (1868) – Mor ho! [Death upon him!]

A beautiful land – Danube2 waters its borders,

And Tatras3 surround it by rock walls,

That land, those proud mountains, those fertile valleys,

It is their homeland; it is the cradle of ancient sons of glory.

Similarly to the human-nature distinction, there is a strong divide between nature and culture. Culture is often seen as something artificial and human-made while nature is created by the environment (Haila, 2000, p.155). Nevertheless, I would argue that the two can be more intertwined than we might think. For example, the Preamble of the European Landscape Convention states that “landscape contributes to the formation of local cultures and that it is a basic component of the European natural and cultural heritage, contributing to human well-being and consolidation of the European identity,” (Council of Europe, 2000, p.7). Nature became an important part of Slovak culture through the depiction of natural landscapes in art,

especially in literature. Nature was used in romantic literature as the symbol of national emancipation from the rule of other nations over the Slovak people. Literature from this period created the idea that Slovakia is a natural country characterised by mountains, rivers, valleys and lakes (RTVS, 2024). However, it was not only literature that shaped the idea that Slovaks are deeply connected with nature and highlighted the importance of nature in the identity of Slovaks. The first Slovak full-length sound film called Zem spieva [The Earth Sings] (1933) tells the story of rural life in Slovakia and its interdependency with nature and the natural cycle as the four seasons change. The film is deemed the codification of the idea of Slovakia as a

country attached to nature and the identity of Slovaks being determined by nature (RTVS, 2024). The representation of nature in art contributes significantly to the formation of a nation’s identity (Novak, 1980 cited in Olwig, 2008, p.74). National identity, is therefore, not constructed only by culture but because nature oftentimes becomes part of culture through art, it also affects national identity and transforms it into something natural instead of artificial (Olwig, 2008, p.73). Even though I spent 5 years in high school learning about how nature affected Slovaks and our identity, I fully embraced nature as part of my national identity only after I had left Slovakia for my university studies.

Since I started my studies abroad…

…I’ve reconnected with Slovak nature and what it meant to me. After having lived in a village of roughly 2,000 inhabitants my whole life, moving to Birmingham was initially a shock. After having lived in a village where I needed to walk for 5 minutes to reach a calm forest, moving to Birmingham made me feel disconnected from nature. Not because there was no nature. Of course, we have a beautiful campus full of green vegetation. However, I suddenly lost the easy access to the nature that I loved so much. I could no longer go to the mountains as easily. I did not only miss my family and my friends; I missed the country and

its landscapes. Every time I go back for a visit, it has become my family’s tradition to go on at least one hike. Last time we went to Vlkolínec. It is one of the last villages in Slovakia where people still live in sync with nature. Gardens full of their own fruit and vegetables, a natural water stream flowing through the village and hens and baby goats running around the village. Nature was present everywhere one way or another. It was amazing to see. In a way, I was jealous of those people and their way of life. I felt like something that used to be so ordinary to me when I was a child, has become something special that I get to experience only occasionally.

…I’ve fully embraced my national identity. At the time I left Slovakia, I was not always proud to be Slovak. During my first year in England, when meeting new people from countries all around the world, of course, one of the first questions was always: “Where are you from?” Almost nobody knew anything about Slovakia other than where it is on the map. “Oh, I’ve never been,” “Is there even anything interesting about Slovakia?” “So, what places would you recommend to visit if I ever went there?” I remember my answer has always been: “Nature… if you ever go to Slovakia, don’t go to Bratislava or Košice but visit our natural

landscapes like High Tatras to see our mountain lakes or go see the national parks such as Slovak Paradise. These are the places worth seeing in Slovakia.” The fact that people did not know anything about Slovakia always made me sad. Nobody ever needed to ask what to see in France or whether there was anything interesting about Spain. But soon I realised how exceptional Slovakia actually is. People from other countries always suggested to visit their capitals or other beautiful cities but hardly anyone suggested to go see their country’s nature and landscapes. Slovak nature is what pushed me to be proud of my country and to show everyone that Slovakia deserves to be noticed.

According to Smith (1991, p.143) among the various elements that shape one’s self, “national identity is

perhaps the most fundamental and inclusive.” National identity and environmental identity are intersected in

many ways in the case of Slovaks. There is a common belief that nature and its beautiful landscapes are part

of us as a nation. Landscapes have become strong symbols as they not only convey various meanings but

they exist in their physical presence (Larsen, 2005, p.296). They have the ability to be a means of giving the

nation a visual representation and a certain level of materiality (Agnew, 2011 p.38-39). More specifically,

national identity is shaped by natural landscape in four ways: “(1) it gives unity to people and place, (2) it

provides this unity with a unique character, (3) it provides people and place with a common origin, (4) it

naturalises that unity and that origin” (Larsen, 2005, p.297). Some landscapes play such a crucial role in the

shaping of national identity that they may even become national icons representing the nation (Daniels,

1993, p.5). In Slovakia, our national identity is largely attached to some of our landmarks. Places such as

Kráľova Hoľa4, Kriváň5 or High Tatras are natural landmarks deeply connected to Slovak identity because

they differentiate us from other states (RTVS, 2024). Our coins feature Kriváň. Our mountains are depicted

on the Slovak flag. Our national anthem (Matúška, 1844) starts with the words: “Lightning over the Tatras.”

Natural landscapes have become national symbols of Slovakia.

The rural characteristics of Slovakia also add to the importance that we as a nation put on nature. Slovakia is

the country with the highest percentage of the population living in rural areas in the European Union (The

World Bank, no date). People with rural origins more often see nature as part of their identity (Sierra-Barón

et al, 2023). It would even seem that environmental identity might be more important for some people than

national identity. In a survey asking Slovaks which option they identified the most with, more Slovaks

identified themselves as conservationist (or “ochranca prírody” in Slovak which could be literally translated

as “protector of nature”) (72%) than as patriots (59%) (Inštitút 2050, 2023 cited in Grečko and Kiripolská,

2023). Moreover, national identity can motivate the formation of environmental identity. Milfont et al. (2020) and

Clayton and Kilinç (2014) found that national identity correlates with environmental identity. National pride

encourages people to recognise their nation’s natural environment as a valuable attribute of the country

which may subsequently motivate pro-environmental behaviour (Clayton and Kilinç, 2014). Thus, it is not

only nature that contributes to the creation of a national identity but it is also the national identity that

supports preservation of nature.

Thus, my national and environmental identity intertwine. Growing up in Slovakia allowed me to spend lots

of time in nature and taught me how important nature is for us and our identities. Slovakia has been

represented as a country of nature in our literature and other forms of art (RTVS, 2024). Because nature is

something that unites us and is seen as a representative asset of our country, it contributes to building of

national identity (Larsen, 2005, p.297). Alternatively, coming from a country where nature is seen as

something to be proud of can result in formation of environmental identity and pro-environmental actions

(Clayton and Kilinç, 2014). Nature, therefore, plays a crucial role in formation of both national and

environmental identity and allows them to influence one another.