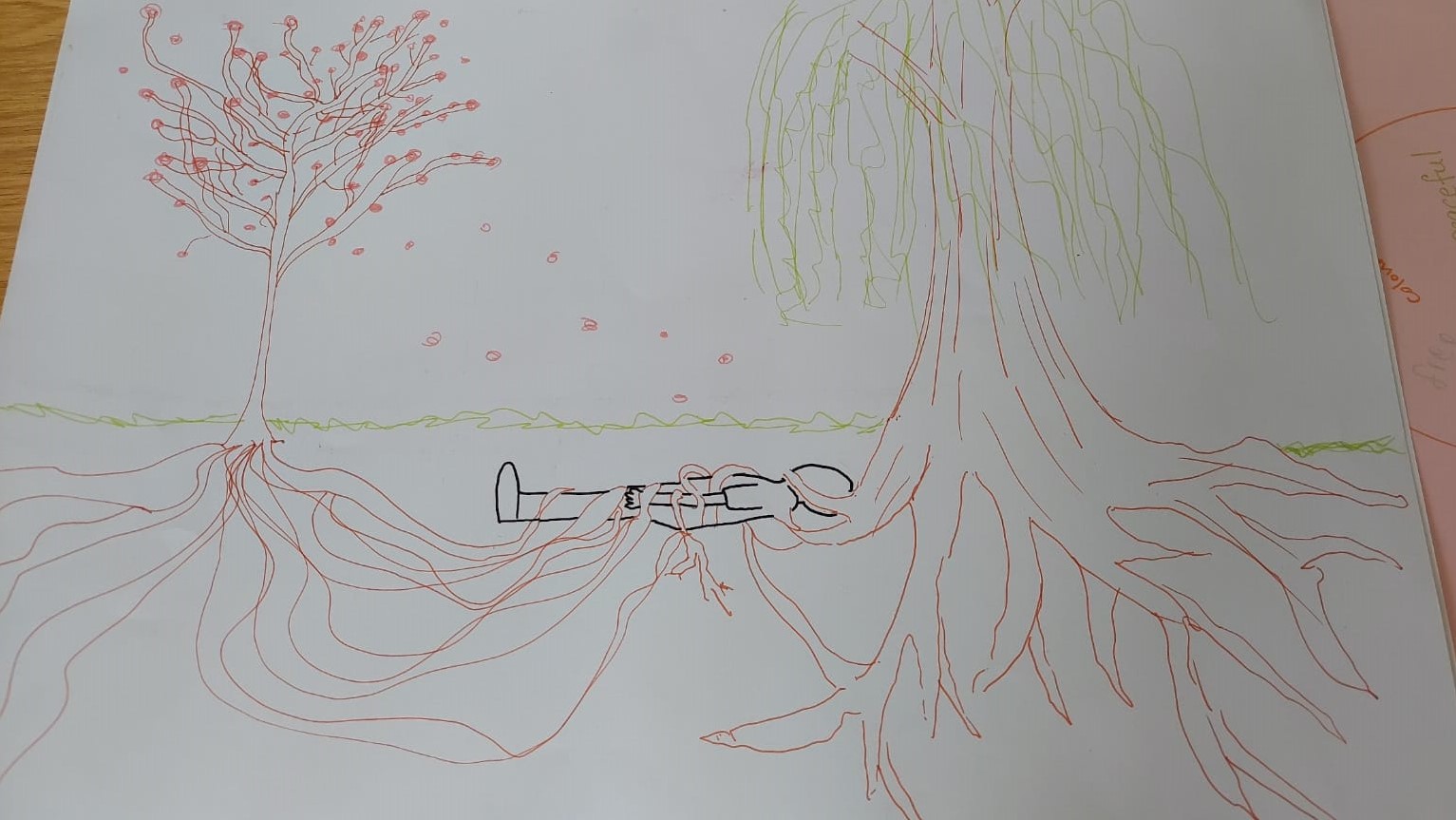

Drawn by Skye Shortridge and Megan Carter

Amaad Amin

My Journey to the Village (abridged)

09.10.2012 Dear Diary,

Today we made our journey to my mother’s village in Pakistan. As we covered the miles ahead, the sounds of the city slowly faded away leaving an unearthly silence. The surface of the roads became rough, the sight of all buildings vanished. As we entered the mountains of Kasgumma, I was suddenly alarmed by the depths that lay ahead. Our driver had begun a descent down the side of a mountain. As I looked to my right, I attempted to slowly look down and before I knew it, I had grabbed onto my mother, as though hanging on for dear life. As my mind became hazy, I had no choice but to admit my life was in the hands of the mountain. With its mercy, would I reach the village. After this encounter, I decided it was a smart idea to not look outside and rather to reflect within and think about my grandad. I had not seen him for a few years, but the thought of seeing him brought me happiness as though a light at the end of a dark tunnel. My mother, however had warned us that he would not be the same as he had 2 been diagnosed with dementia. My brother told me about how my uncle offered to bring my grandad to the UK, but for some absurd reason he rejected this offer. He talks about wanting to stay in his country and to spend the remainder of his life at his home. For a moment, I felt a sense of relief as the distressing long journey reached its end. It was at that moment I looked back out of the window and noticed the tall trees leaning over our car, evoking a sense of darkness. It is at this moment, that I feel trapped as though never to escape from the clutches of nature.

As we were playing, I watched as [my grandad] dug some lines in the dirt for an irrigation system he had been working on. His diagnosis had not stopped him from living the life he wished. However, it surprised me why he would rather spend time alone trying to work on one of his environmental projects. Surely, in his situation he would rather sit inside and enjoy watching some TV or spend his time in the company of people. Rather, it seemed he enjoyed being alone. I personally do not know how anyone can enjoy being alone.

09.10.2022 Dear Diary,

Today, we went back to my mother’s village. This was the first time I visited her village since my grandad’s death a year ago. As we left the city, we left behind those sounds which constantly followed me with every step I had taken in the city. All of them slowly faded away, leaving me to finally be able to hear my own thoughts once again. I sat in silence, taking in the moment of peace when I felt the wind slowly flow through the car. I felt a gentle breeze flow through my hair. It felt as though a loved one had compassionately brushed their hands through my hair, bringing a sense of warmth. The taste of the breeze was a familiar one, and instantly memories began flooding my mind reminding me of my grandad and his smile that never vanished even as the days became tougher. No words could do justice for the view that blessed my eyes.

As we drove up, we stopped by the family graveyard to visit my grandad and to say our prayers. It was as though I could feel his presence in the environment, as my connection to nature strengthened, so did my connection to my inner spiritual self. After settling down, for a moment I felt a sense of loneliness as the house felt empty. Without my grandad it no longer seemed the same. I decided it would be a good idea to take a walk in the courtyard. As soon as I stepped outside, the feeling of loneliness was immediately replaced by contentment. As I looked out over the courtyard, I took in the view, wishing that the moment would never end. It felt as though everything was interconnected and the sense of unity filled my heart as I felt myself not being able to resist smiling. After reflecting on the view, I decided to go down to the spot where we had once played cricket and stood where my grandad had stood when he was digging lines for the irrigation system. A sense of realisation flowed through my veins as I thought about how I had felt about the village 10 years ago. I felt silly remembering how I felt. I had thought my grandad was alone, yet now I realised he was anything but isolated. No wonder he had refused to leave, for him to have left would have meant him leaving behind a priceless friendship. What I have seen today leaves me proudly saying: this is how my country is. My beautiful country has provided me with a priceless gift: love for nature. In every step you take, you’ll find a love story. This is how my country is.

Maya Biddulph

Poem & reflection from the Heart of England Forest Trip 27 March 2023

OF EARTH

What would it be like if I was buried underground?

With my eyes wide open

Would I be covered in webs of mycelium,

Would the worms slip and lick over my skin,

Would it be warm, or cold?

Would I feel the trample of feet above me,

Would I be aware of the surface,

Would roots tangle round my fingers and knot through my hair?

Would the soil embrace me, or the stones cut me?

Or what if I existed

In the topmost branch of a tree?

Would I feel vertiginous or would I feel free?

Would I feel indifferent when the birds claw onto me,

Would I sense the wind kissing my cheek,

Would I feel tall or would I feel small?

Might I break off in a sudden storm and land on the ground and be buried…

And be buried underground?

Reflections: Watching kids in the dirt

Kids, the boundary of this field is your space. I am not your teacher. Away from the

aseptic, smell-less, mechanic interiors of the home and the classroom, this is your space. Like

a puppy, you need to run around, stamping your feet over the earth, to shout and clamber and

roll over and in it. “Look at this stick, it’s so smooooooth!”, you say. Like a wide-eyed, shy,

and wary kitten, you want to sit and ponder over a dandelion. Smell this flower; see this

buttercup reflecting golden hues on this one’s chin. You develop your senses, and you deepen

your sense of self. Your identity is purer in this field than it is in the classroom. Whilst you

are here, the classroom, the house, remains out there: outside this sphere of freedom that we

have created for you. In this stretch of daisies and occasional fox excrement, you are freed

from the adult gaze, the daily attrition of your innate and childish personality. You do not

need to be standardised, sensible, lucrative, clean. Here you are accepted as a dirty child

because the disparaging and incriminating inflection of that word holds no weight here.

I envy you…

Manveet Kaur

Manveet offers some reflections on what it is to be ‘native’ in A Natural Conversation

A Conversation in Nature

Aman Bassi

Aman talks in this (abridged) essay about waste pickers in India.

By 2050, the annual production of global waste is expected to reach 27 billion tonnes. Today, 80% to 90% of all municipal waste is dumped in landfills without proper waste management systems in place (Kumar & Agrawal, 2020). [In] India the distribution of waste is harmful to the poor in various ways. India’s annual production of municipal solid waste (MSW) is around 62 million tonnes, of which, 43 million are collected, 31 million goes to landfill, and only 12 million are processed (Raychaudhuri, 2022).

India’s lack of infrastructure is a large reason why its waste management systems are inadequate. Across 700 villages, 36% have public bins, and 29% have a public waste collection vehicle (Pandey, 2022). The lack of infrastructure in India stems from its increasingly service sector-driven economy. The shift of focus from the production of goods to outsourcing technology services has meant that there is less government investment in its industrial sector (which includes waste management systems). As a result, India’s infrastructure has become outdated because money is being pumped into the development of its technology services to maintain the funding of new projects. Previously dubbed India’s cleanest city, it is now one of the most polluted (English, 2020). The boom in technology campuses attracted businesses and people which naturally led to more consumption of goods, consequently more waste being produced. As the city’s infrastructure remained the same, the waste that was produced was not processed properly and there was more waste than the city could handle. Now, the streets are riddled with waste, and it is common to see large piles next to technology campuses. The solution? Companies eventually realised that the cheapest way to get rid of the trash was to pay for it to be loaded onto trucks and driven outside the city where it would be dumped (English, 2020).

Another reason for India’s poor waste management system is because of its population growth and rapid urbanisation. With more waste produced, the already inadequate waste management systems are put under pressure. This is exacerbated by rapid urbanisation as the growth of India’s megacities, such as Mumbai and Dehli, means that waste production is concentrated in densely populated regions, adding to the severity of the human and environmental impacts in those regions (Kumar, et al., 2017). Megacities are the main source of the problem because they generate around 70% to 80% of India’s total waste (Kumar, et al., 2017).

The lack of segregation of waste at the source is also an issue. Recycling in India is almost non-existent. The rates of recycling are so poor that figures are unknown because most of this is carried out after waste is dumped and separated by the informal sector (Dobrowolski, 2021). The reason for the low recycling rates and segregation of waste at the source is that there is both a lack of interest and a lack of resources to recycle and manage waste (Ahuja, 2022). The implication of this is that India’s waste management systems are ‘so far gone’ that there is no incentive for people and businesses to try and start recycling.

One of the most significant consequences of India’s poor waste management system is the emergence of the informal sector. Waste pickers make up a large part of the informal sector and are self-employed workers who gather, segregate, and sell waste by hand to wholesalers, who then process the waste into goods (World Economic Forum, 2022). The reason waste pickers remain in this role is because there are no alternatives. It provides them with an income and a means of survival. Despite its adverse health impacts, “waste picking is often the only source of income for families, providing a livelihood for significant numbers of urban poor and usable materials to other enterprises” (Kumar, et al., 2017). Around 25% of waste pickers do not have a toilet in their house, and 70% have only a single room (Singh, et al., 2023).

However, the informal sector is one of the most important aspects of India’s waste management. Without this industry, there would be almost no waste management in place. A recent study found that waste pickers in India recovered 20% of waste and that 80,000 people recycled approximately 3 million tonnes of waste (Kumar, et al., 2017). By segregating waste, waste pickers can help with the recycling process as they sort materials that can be sold and reused to make goods. Without the informal sector, the situation would be worse as incineration produces 25 times more greenhouse gas emissions (WIEGO, n.d.).

A consequence of the distribution of waste is the implications it has for health and human rights. Large tyre dumps in India collect water which becomes stagnant over time. This attracts mosquitoes and contaminates the water supply, increasing the risk of spread of diseases such as malaria and dengue (Kumar, et al., 2017). The burning at dump sites releases toxic chemicals such as methane, which causes respiratory diseases including lung cancer. The air pollution caused by the burning also leads to bacterial infections, anaemia and even asthma (Kumar, et al., 2017). These effects are amplified for people living near dump sites, and for waste pickers in particular who deal with waste every day, there are additional health implications. Waste pickers are scratched, cut and impaled by sharp objects such as needles. The lack of even the most basic equipment such as shoes and gloves is a major reason for injuries. An example of this can be seen in Figure 1, where women and children shift through the trash with their bare hands.

Figure 1 Female waste pickers sorting waste in Jalandhar, India

Source: Global Development Institute, 2018

Additionally, Figure 1 shows the unsanitary work of waste pickers. This links to how waste picking violates human rights. Some formal examples of this include hazardous working conditions without proper safety measures in place, exclusion from social security systems and financial services, and no access to clean water or decent housing (Tew, 2023). WIEGO (Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing) describes waste picking as the lowest-ranked urban informal occupation, with a large number of workers being uneducated women and children. This is because of the caste system in India which keeps certain castes in this line of work, Dr Sylvia Karpagam calls waste picking “a form of caste-based slavery” (Dandapani, 2017).

The final consequence we discuss in this essay is the environmental impact. An example of this is in New Delhi as seen in Figure 2. As India’s largest dump site, it is set to become taller than the Taj Mahal over the next few years. For reference, the dump site is around 65 metres high compared to the Taj Mahal which stands at 73 metres high. Also, so much waste has been dumped that roads are made to allow trucks to drive to the top. Dump sites with organic waste undergo anaerobic decomposition which leads to the release of methane gas. As a result of burning dump sites, toxic chemicals and large clouds of smog appear which contribute to increasing global temperatures (Kumar & Agrawal, 2020).

Additionally, Figure 1 shows the unsanitary work of waste pickers. This links to how waste picking violates human rights. Some formal examples of this include hazardous working conditions without proper safety measures in place, exclusion from social security systems and financial services, and no access to clean water or decent housing (Tew, 2023). WIEGO (Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing) describes waste picking as the lowest-ranked urban informal occupation, with a large number of workers being uneducated women and children. This is because of the caste system in India which keeps certain castes in this line of work, Dr Sylvia Karpagam calls waste picking “a form of caste-based slavery” (Dandapani, 2017).

Figure 2 The Ghazipur dump site in New Delhi is on course to grow taller than the Taj Mahal

Source: ‘Ghazipur landfill mountain will be taller than the Taj Mahal’, 2019

Egle Adomaityte

Egle reflects on a famous Lithuanian poem by Kristijonas Donelaitis called The Seasons, to chart her own journey of environmentalism. She notes: ‘As Freya Mathews finds herself, one discovers wisdom not through strategic trial and error of science but through our own agency of “experimentation” and discovery of creativity, which fits everything in Nature’ (2009: 350).

(Abridged)

To me, the sustainable lifestyle was about restraint, self-control, and discipline. I kept questioning why my desire to be in tune with the Nature is restrictive and constraining. If Manuel Arias-Maldonado argues that sustainability means to be freed from Nature, my ties, with which my relationship with Nature has been constrained, must be cut off (2013). Furthermore, tools to cut those ties were found in my reflections on literature class in high school, where I was taught imagination and deep discovery of the meaning of the unmaterial world. ‘The Seasons’ by Kristijonas Donelaitis is the most prominent Lithuanian poem taught in schools. It offers answers on how humans should embrace true change in their environmental journey. Every Lithuanian student is familiar with this poem written back in the XVIIIth century. Nevertheless, I never looked at it as something that could untangle my complex relationship with Nature. Only after I started studying Climate Politics module and was encouraged to explore Climate Action through the prism of creativity and freedom, I rediscovered ‘The Seasons’. Donelaitis’s extraordinary use of old yet simple words, illustrates the life of villagers in Lithuania. Nevertheless, I used to overlook the indirect yet rich legacy towards ecological empathy that Donelaitis offers.

“Now the sun rose again to rouse the world

And laughed to topple down chill winter’s labors.

And cold’s creations, with the ice, diminished

As foam of snow changed everywhere to nothing.

Soon the bland weather stroked and woke the fields,

Called up herbs of all species from the dead.’

Donelaitis opens his poem “The Seasons” by unravelling the parallel between Nature and humankind. He “humanises” Nature by endowing it with human qualities. Even though such an approach might seem anthropocentric, in this context, the humanisation of Nature is positive, as it does not ‘erase’ Nature but allows me to explore the linkage with the natural environment (Eden, 2001, p.83). It reveals the closeness humans and nature share and emphasises their interconnectedness. Donelaitis’ precise and vivid illustrations of the environment invite me to not only listen to what the author himself wants to say, but also to what Nature speaks to me. Donelaitis empowers the voice of Nature, which evokes not only the land and herbs but also my inner reflections on my place within this interconnected network of the natural world.

Suppose something fundamentally deeper and unable to get a grasp of, such as the mythical connection and commonality, necessitates escape from rational constraints and allows to build up new outlook (ibid., p.103). In that case, it is the standpoint from which Donelaitis’s poem is reborn as this moral liberation. His poem speaks about the acknowledgement of our, as individuals, role within the networks of Nature that plays the primordial part in leading tuneful and consistently sustainable lifestyle. It speaks about synergy with the Nature. Thus, there is something more behind the lines of Donelaitis poem in which the awakening spring calls up all the species. The sun rose to rouse the world, he says. With such a simple sentence, Donelaitis opens up a fundamental element that made me realise the problematic relationship between me and the ‘sustainable lifestyle’. And that element is harmony.

‘And rats with skunks walked out of their cold crannies

As crows, ravens and magpies, with the owls,

Mice and their offspring and the moles, praised warmth.

Beetles, mosquitos, flies, a bounce of fleas

Formed their batallions everywhere to plague us

And sting both peasant and his genteel Sir.’

Donelaitis includes the smallest and seemingly insignificant creatures, such as rats, skunks, crows, and flies, demonstrating his deep appreciation of diversity. The use of personification in describing the animals and insects, such as “praised warmth,” indicates he saw creatures as having agency and a voice in the natural world. Additionally, the final lines of the passage suggest that Donelaitis recognised the potential for conflict and a struggle between humans and the natural world, with the insects and animals “plagu[ing]” and “sting[ing]” both peasants and their noble counterparts. Yet, the conflict Donelaitis writes about is not about ‘either you or me’ but rather the struggle of life and effort to coexist in complex natural relationships (Naess, 1973, p.96).

While reading Donelaitis, I realised that my concern for environmental protection was ego-centric and ignored the voice of Nature. I used to organise clean-up days and visit forests to “clean up the environment,” yet my urge to take well-intentioned actions stemmed from moral isolation, thus ignored real, lasting change (Ashley, 2022). Whilst less litter in the forest is an appreciated outcome, the instrumentality of my actions ignored questions on whether natural systems can thrive under continuing uncertainty for the Natural world within a wider context. An essential ingredient to my already existing understanding that I somehow must help the environment lacked compassion and equal concern for not only humanity but the overall environment (Fox, 2001, p.57). Donelaitis’ portrayal of the natural world as a complex web of relationships, where every creature has agency and a voice, has inspired me to approach environmental protection with a new perspective. Rather than imposing my will on the natural world, I will strive to listen to its voice and work with it to create a harmonious existence for all beings.

Reflecting on my journey with a sustainable lifestyle and environmental ethics, I realise that my ‘environmentally friendly’ actions reached me earlier than environmentally friendly thinking. Donelaitis wrote that a man’s life is a cyclical struggle dictated by the changing seasons.As Freya Mathews finds herself, one discovers wisdom not through strategic trial and error of science but through our own agency of ‘experimentation’ and discovery of creativity, which fits everything in Nature (2009, p.350). The scholar calls this ‘piercing it together’ approach con-frontational, stemming from science, counterarguing distance from rationality and subversion to mythical connections (ibid., p.251). Nevertheless, her point is that there is a need to embrace the dynamic nature of environmentalism and approach it with an open mind and a willingness to experiment and learn.

Donelaitis’s writing invites us to slow down and appreciate the natural world, reflect on the importance of mindfulness and being present in Nature, and cultivate a deeper connection with the environment and the world around us. And whilst Val Plumwood, in the face of environmental crisis, invites readers to create a new “we” and find new ways to live (cited in Gibson-Graham, 2011, p.2) I find myself looking back to how Lithuanians lived before and trying to adopt their approach instead of inventing something new. [Donelaitis’] poem demonstrated that true environmentalism, as many of us strive for, is not an unimaginable goal but something that was lost and can be restored on this Earth. And even though ways of how to restore it remain unknown to me, I will keep exploring and experimenting.

‘We need time, so let us wait the time in patience.

Till the fields bring yield, let us not tire of waiting.

You, dear God!

You, our heavenly benefactor!

You, in millennia before we could reflect,

Knew already how we should be brought to Light,

Knew our needs when we should come to meet that day …’

Josephine Tan-Sikorski

Jojo gives us a fascinating insight into ‘sonic rupture’, illustrated through a moment in a garden (abridged)

Escaping the anthrophony – exploring sonic rupture and connectivity

“Chirrup, chirrup, caroo, caroo” sing the chiffchaffs nestled among the blossoming hawthorn trees. Their call signals that dawn has come. A few yards away, they are joined in symphony by the willow warblers who sit perched atop several silver birch branches. Across from them and overhead a plot of daffodils which light up the sides of the garden are the coal tits. They flitter across a couple of nearby young oaks, taking short yet wistful breaks on each branch as they call out to those around them. Further down the winding garden, some red-bellied robins hide above a shallow, quaint stream. As the sun continues to rise, the garden of Bines farmhouse becomes encompassed by the sweeping birdsong of its many feathered visitors. Each species of bird calls out to one another sending distinct messages in their own unique voice. The multifariousness of each chirp and tweet begins to overlap and weave into innumerable harmonious melodies stretching across the busy plot of land. The stream murmurs and babbles as it feeds into a nearby river, adding further complexity to the musical score of the garden as the water gently trickles across scuffed rocks.

As the morning progresses, thick clouds paint the sky grey, and a gentle rainfall starts to fall. The gentle patter evolves into an erratic drumming. Rain droplets splash off the farmhouse’s faded red bricks before trickling down the drain, whilst other droplets bounce into quick-forming puddles. The natural soundscape is continuously variable and full of life. Different bird species congregate on the great sycamore tree, sitting at the heart of the garden. Its long, spindly branches reach out towards every corner and side of the garden. Some birds begin to feed as others use the canopy of leaves and thick branches to shelter from the downpour. The owners of Bines Farmhouse haven’t visited the garden in a few weeks, but these frequent downpours have kept the garden’s ecosystem content.

Slowly poking out from a patch of overgrown damp grass on one side of the garden, a seemingly timid shrew emerges. Letting out a series of sharp squeaks, often undetectable to human ears, the shrew’s high pitch call cuts across the air. It carefully waits and listens, using the sonic reverberations as a tool for echolocation. Having properly stabilised itself above ground, the shrew’s movement drastically changes in tempo as it begins to dart across the width of the garden, making its way towards the neatly sectioned off vegetable plot that the owners of Bines Farmhouse would usually tend to each afternoon. The now wet ground has provided enticing conditions for further walks of life as a crowd of slugs slowly make their way towards the plot. The shrew’s long whiskers find their way to the unsuspecting slugs as it begins its afternoon feast.

Suddenly, the garden’s melodies are joined by a faint rumbling in the distance. The rumbling begins to crescendo, turning into a disjointed and vociferous crunching. A shiny orange excavator followed by a dust-coated truck pull themselves up along the steep cobblestone drive and around to the front of the farmhouse. The engines grind to a halt and the vehicle doors swing open. The drivers brashly converse with each other for a few moments before getting back into their vehicles and driving towards the entrance of the garden. As the wheels press forwards onto the soft green grass, the garden animals freeze. The reverberations that the shrew is now feeling have drastically changed from earlier. This alien noise translates into alarming pulsations and signals danger as the shrew darts into a crevice of the sycamore tree, doing its best to burrow into the ground. The birds fly frantically away from the sycamore and surrounding trees as the vehicles move closer. Their calls have changed, turning from playful chirps into urgent squawks. The drivers do not notice as they nonchalantly clamber out of their vehicles. The whirring of the engines alone is enough to silence the melodic and diverse sounds of the garden. The drivers begin to survey the area before one climbs back into the excavator and proceeds to dig up the earth. The sharp metal claws pierce the spongy ground as the work begins. Disoriented, some birds linger on the garden walls. Their calls are now muffled and begin to still.

The other driver trots over to some of the thinner trees near the excavation site and revs up his chainsaw. As the blade gnaws away at the wood, splinters of history are scattered across the lawn. The air is filled with loud and turbulent cracking and crunching sounds before the trees fall to the ground with a loud thump. Time drags on as the metal machines continue to bellow and growl. As the sun begins to set, the engine noise abruptly stops. A brief silence washes over the half dug up garden. The drivers march over to the great sycamore tree and contemplate what to do with it.

The shrew, now burrowed underneath the ground, trembles with fear as each step above ground shakes the earth around it. Hesitantly, the drivers decide to spare the tree as they jump into their vehicles and head home for the day. An unsettling silence washes across the garden. The garden has now taken on a stagnant presence when hours earlier it was rife with character. What had once been a carefully cultivated garden, was now an uprooted plot of land. The previous vibrant colours which were once sporadically dotted around had been raked away by metallic claws. The sun is beginning to set and what would usually be a choir of birdsong is a disjointed series of soft and broken chirps. The carefully composed musical score of the garden which had been cultivated over several years has been stripped from the garden in a matter of hours. What is left is a strange stillness, unfamiliar and isolating to the garden’s remaining inhabitants.

A brief reflection on sound

To conceptualise the dynamics of sound between humans and non-humans we can look at the anthrophony, used by Pijanowski et al. (2011, 204) to describe human generated sound. This differs from the geophony, which refers to planetary sound and biophony, which describes the collective sound made by non-human organisms within a certain biome. Whilst urban city-dwellers are not the sole contributors to the anthrophony, noise tends to be much more prevalent in the city than in other areas (Pijanowski et al., 2011). Moreover, the anthrophony can be broadly split into positive anthrophony and negative anthrophony with the former encompassing sounds like music and communication and the latter encompassing sounds which have been described as ‘uncorrelated acoustic debris’ (Krause, 2012, 160; Calvino, 2022).

The consequences of the negative anthrophony extend immensely beyond adversity for humans and are illustrated more widely in the environment with noise acting as a powerful tool in silencing non-human species. This is especially problematic because whilst humans live in an ever-focused visual culture, many non-human species are dependent on sound (Robinsong, 2022). Even subtle changes, such as the increase in ambient noise in the Arctic, have created debilitating conditions for aquatic creatures when carrying out their daily navigation (Han et al., 2021). Moreover, whilst some species such as birds have learned to adapt and modify their songs to frequencies that are able to cut through the city noise, this has not come without the cost of driving huge numbers of bird species to extinction (Wood et al., 2006, Harvey, 2019).

Looking further into power dynamics, Haskell (2022, 258) terms the phrase maestro species which arises ‘from the Latin magister, he who is greater’ to expand on the hierarchical relationship between humans and non-humans, or perhaps what can be referred to as a sonic hierarchy. This concept of the maestro species is seemingly grounded in anthropocentric ideology which stringently separates humans from non-humans (Eckersley, 1992, 38). It seems bizarre to me that this sonic hierarchy should exist when it is so clear that the effects of the negative anthrophony pervade the lives of all species. Thinking [differently] means considering the sonic futures of all species, whether that is partaking in decision-making at higher levels and imposing noise restrictions, or in aspects of day-to-day life. For instance, in Ebenreck’s (1983, 42) farmland ethic, she asserts the importance of ‘learning to “listen to the land”’ which could mean spending time in an area of nature and looking closely at the terrain and over time gaining an understanding of what the land needs and how it changes as we interact with it. As Staddon et al. (2023, 350) eloquently explain, ‘listening attentively may help us better understand the ways in which our lives are entangled through interactions and mutual impacts, and how we can live in the world together’.

Skye Shortridge

Skye talks about our relationship with nature, the question of agency, and the work of Bruno Latour.

Our relationship with Nature

Niharika Manu

Niharika takes a ‘rhizomic lens’ to the concept of interconnectedness.

A rhizomic lens on nature

Louis Stanbury

Louis shares a conversation on nature with his grandmother Magdalena.

A 4-part conversation with granny

Zoe Wakeling

Zoe produces a beautiful and evocative story inspired by the Karuk Tribe of the Klamath Basin in Northern California.

The Observer

She was born from the soil; she was born from everything. Atoms and molecules, reactions and evolutions, stories and memories – they became her. She was everyone, a sticky web of relationships impossible to untangle. This web defined her, for she did not exist outside of it. This confused her at first, but she soon came to terms with it. She liked being undefined.

As her vibration senses knitted into existence, waves of polyphony rolled through her. Whispers and screams and laughs and songs, each communicating their own harmony. It was awakening. Melodies of the forest ebbed and flowed, and through them, she navigated her way into tentative understanding. One particular conversation drew her attention. A northern spotted owl cooed pleadingly to his tanoak cousins, whose numbers were diminishing in a haze of neglection. The owl was angry; his ancestors had told him that the tide was turning, that his cousins were now protected. Yet what use was protection if all that was saved were the means of extraction? Forests conserved to fuel distant wars, valued for the promise of violence held in their gentle branches. The owl squawked indignantly at the oaks being degraded in this way, but clung to their timeless wisdom, knowing that salvation lay in every fibre of their gnarled presence.

The owl spread his wings, and so did she. She let herself wander aimlessly, but not without purpose, settling down within the forest’s steady breaths. In, out, in, out. Millennia transpired in a single sigh. The forest’s canopy shrouded its relatives in a protective embrace, its breath occasionally becoming more laboured with the effort of survival. She had faith in the forest and the soil that had birthed them, knowing their entanglements remained strong even as earthly entities fell victim to greed. The breeze guided her focus to the water’s edge, where the riverbank supported the water’s eternal journey. A kaleidoscope in every droplet, each more precious than the gold pumped from the river’s depths. Shimmering beneath the surface, a coho salmon danced with the rocks, a rare sight among the debris of dams and hydraulic mines. The river’s song guided the salmon home, a coordinated rhythm pumping through its veins. They needed each other, the river and the salmon; they were tied through symbiosis and spirit. She was aware of an urgent need to ensure they were cared for, for the sake of all those both past and present. It was a legacy and a promise for the dead and the yet-to-be.

An unfurling of smoke beckoned her back to the forest’s nucleus, restless in its metamorphous swirls. It rose steadily from the smouldering brush, a dense body of greys before dissipating to nothingness. She felt no fear of the smoke. Its whispering assurances were unnecessary here, for the forest’s entities welcomed its presence. The oaks sighed in relief as tender flames cleansed their young of infestation, clearing the way for regeneration. Back in the river, the salmon gave thanks to the smoke’s blanket of protection, a counterweight to the algae’s insatiable hunger for sunlight. She knew this smoke was precious so long as harmful misunderstandings prevailed. She wished more humans listened to the smoke’s restorative lullabies.

But for now, she was grateful for this small, resilient group of humans who did choose to listen. As they set alight precisely selected patches of undergrowth, she felt their reciprocity radiate waves of care into the land. They too heard the chattering of the owls and the oaks, and heeded their advice that too often fell on deaf ears. The forest’s entities instructed these humans, guiding them to be at one with the fire and learn its medicine. The flames were not theirs to control, but were generous in their lessons as they jumped and swirled with playful merriment. She let this celebration consume her, absorbing its embryonic potential.

These humans were cautious, for they knew their activities could send them behind bars. Too many had become prisoners of progress, criminalised for refusing to see the forest as an untapped pool of resources. Incomprehensible papers, foreign laws, stolen lands. All created barriers to burning, obstructing practices older than the English language. And still they burned. She watched as another group followed their memories, returning to a rare patch of hazel that had been gifted with fire in a previous season. Here, the stems stood strong, gleaming from care and love. They pitied their frail neighbours, whose misfortune had manifested into weak, breakable limbs. The fire-treated stems were arrogant, smugly aware of their value as they were gathered by withered human hands. These hands soothed the less fortunate, comforting them with reassurances that functionality did not define their worth. Still, they watched with envy as the humans congregated, jealous of the joy the chosen would give life to.

And so they gathered. Generations of knowledge converged as the hazelnut stems entwined, each motion giving thanks to those who came before. The humans rejoiced at the quality, at once again being able to weave with fluidity as fingers reached back to distant memories. The brittleness of past pains led to strengthened resolve, all attention centred on the joyful art of healing. A moment of resistance through shared creation, refusing to be dissolved into the drudgery and hardships of civilisation. Baskets were made and so were souls. She felt regenerated by this ceremony, each connection forging stronger seeds of hope. Warily optimistic, she released herself back into the soil, looking forward to the day when they would join her.