A Vessel for This Life and the Next

A Decorated Naqada II Period Jar

Steven Gregory

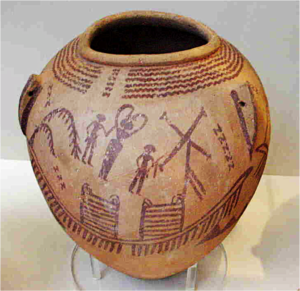

One of several predynastic objects in the Eton Myers Collection at the University of Birmingham, ECM 1868 [1] is a buff-coloured D-ware[2] globular shouldered jar which, from its style of manufacture and decoration, may be dated to the Naqada IIc-IId Period,[3] (c. 3300-3200 BC), when the type occurs in funerary contexts over a wide area of Egypt. While little can be said concerning the exact provenance of the pot itself,[4] the vessel is, nonetheless, informative regarding the culture in which it was made.

|

|

The vessel appears to have been hand made rather than thrown on a wheel.[5] The base was likely formed by pressing the clay into a mould, a ridge can be felt around the internal surface suggesting that the body was then built onto the base by coiling before being smoothed by the potters’ fingers.[6] The rim was similarly drawn out by hand, leaving a telltale ridge where the extruded material contacted the exterior surface. The piece is slightly imperfect in that there is a small indentation on one side, near the base.[7] The pot was quite evenly fired, leaving no patches of discolouration, before being decorated with a naturally occurring ochre, and then re-fired to bond the paint to the surface of the clay.[8]

The decoration consists of a series of four wavy lines extending around the circumference of the pot, near the rim, with, on two opposite sides, further pendant wavy lines extending down the body of the vessel. Further decoration appears in what may be interpreted as representations of a pair of oared ships: each having two deck-houses one of which, on each boat, is surmounted by a fetish of some kind. A similar fetish is mounted at one end of each boat and, while by no means certain, the position of the oars and the curvature of the fetishes themselves – points which may imply that the vessel is in motion – indicate this fetish to be at the prow in each case.

There is little to indicate the precise use intended for the pot – other than a rather generic function as a container.[9] The fabric type, being rather less porous than Nile clays, does suggest its suitability for containing liquids; more so as the outer surface has been carefully smoothed to lower porosity yet further. Although not completely impervious, the vessel could certainly have been used to hold water, the small amount of liquid reaching the outer surface would evaporate: an endothermic reaction which would lower the temperature of the remaining contents. The three perforated lugs spaced equidistantly and fashioned into the vessel just below the rim suggest that it was meant to be suspended – in a shaded corner as an early exemplar of the water-cooler, perhaps.

|

|

From this single example, the decoration seemingly offers little information. The wavy lines may be interpreted as symbolising water and, with the boats, present the notion of a Nilotic or nautical theme: one perhaps of some specific interest to the owner of the object. Yet, as indicated above, this is one of a number of similar vessels – such as the examples BM EA30920 and BM EA49570 – recovered from graves of the period which together exhibit a range of motifs including those on the pot in question.[10]

From this it is apparent that at this relatively early point in ancient Egyptian history a canon of art had developed which was common to society at large, or at least to that section of the wider community which were able to acquire or afford such items. Within that social group, it seems reasonable to infer that the symbols in question had meaning. Unfortunately, those precise meanings may remain unknown as no contemporary literary records exist to give any explanation. However, some reasonable conjectures may be offered when the canon is viewed in light of both contemporary and later developments, particularly in funerary art, but also art more generally as used in the wider ritual landscape where depictions of a similar range of symbols are more clearly associated with elite elements of society, and in particular with kingship.[11]

|

|

It seems probable, therefore, that while likely intended as a grave good, the vessel’s decoration is indicative of some degree of hierarchical structure in the society of its living author and, moreover, that structure was not dissimilar from – and may perhaps be seen as a nascent form of – that of the subsequent Pharaonic Period. The owner of such a vessel was likely a senior member of that society, and the jar ultimately formed part of his burial assemblage as a marker of high status in this life to be projected into the hereafter.

[expand title=”Endnotes”]

[1] The boats on opposite sides of pot ECM 1868 to vary slightly with regard to the nature of the fetish mounted on the right hand deck house.

[2] Classified by Petrie (1901: 15) as ‘Class D, Decorated Pottery’.

[3] Hendricks 2006: 77-82

[4] There is no information recorded in documents relating to the Eton Myers objects which gives any indication as to how ECM 1868 came to be in the collection (Stephanie Boonstra: personal communication).

[5] Measuring around 18 cm in height, around 19.5 cm in diameter at its widest point, with an opening of 8.9 cm and a base diameter of 7cm, the pot was manufactured from Marl A: a type of clay quarried in the desert regions of Upper Egypt. This example has finely ground inclusions of both limestone and mica. The fabric seems too course to be A2, the wrong colour for A3, and from the finished appearance seems most likely to be Marl A4; however, there being no clean breaks from which to investigate further, the fabric type cannot be ascertained with absolute certainty.

[6] The marks of this action remain visible on the interior surface of the jar.

[7] This imperfection was likely caused by handling, or perhaps by leaving the piece leaning against another surface, before the clay was dry.

[8] I am grateful to Carla Gallorini for her advice, guidance, and helpful remarks during our physical examination of the vessel.

[9] There are no traces of residue, or any staining, within the jar to indicate that it was ever used for any practical purpose.

[10] For further information regarding this artistic repertoire which, in addition to wavy lines and boats, often included human figures, plants, animals, and a variety of fetishes and symbols which are dispersed over the decorated areas without the use of registers see, for example, Robins 1997: 30-1. Specific examples of such decorated wear include those at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge: E170.19391, a jar decorated with two ships, a hunter, a goddess, and an antelope; and E.1.1928, decorated with boats remarkably similar to those on ECM 1868 but having no wavy lines. A jar decorated with ships and standards again bearing remarkable similarity to the pot subject of the present discussion, albeit somewhat larger in size, is a globular jar in the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva (Inv. 20607) which depicts the same pattern of wavy lines beneath the rim and in pendant form together with a ship and with additional geometric shapes and a row of birds – ostriches, or possibly flamingoes. A comprehensive discussion of early decorated ware exhibiting elements of pharaonic royal art is given by Williams et al. 1987: 245-85; in this respect, see also Hendrickx et al. 2012a: 296-308, and, with particular emphasis on the significance of boats as iconographic elements symbolising royalty, Hendrickx 2011: 16 and Hendrickx et al. 2012b: 1068-1081.

[11] Examples from the range of symbols in question is evident, for example, in the posited royal tomb 100 at Hierakonpolis which is decorated in the style of contemporary Gerzean art. Of particular note are the depictions of ships with deck-cabins and fetishes (Case and Payne 1962: 14-18). More refined depictions of boat procession in the depiction of royal ritual, ceremony, and display abound in the repertoire of monumental art throughout the Pharaonic Period (Gregory 2014: 65-67).

[/expand]

[expand title=”Bibliography and Further Reading”]

Case, H. and J. C. Payne. 1962. ‘Tomb 100: The Decorated Tomb at Hierakonpolis’, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 48: 5-18.

Gregory, S. R. W. 2014. Herihor in art and iconography: kingship and the gods in the ritual landscape of Late New Kingdom Thebes. London.

Hendricks, S. 2006. ’Predynastic – Early Dynastic Chronology’, in E. Hornung, R. Krauss, and D. A. Warburton (eds.), Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Leiden – Boston, 55-93.

Hendrickx, S. 2011. ‘Hunting and social complexity in Predynastic Egypt’, Bulletin des séances: Mededelingen der zittingen 57, 237-263

Hendrickx. S., J. C. Darnell, M. C. Gatto, and M. Eyckerman. 2012a. Iconographic and Palaeographic Elements Dating a Late Dynasty 0 Rock Art Site at Nag el-Hamdulab (Aswan, Egypt), in D. Huyge, F. Van Noten, and D. Swinne, (eds.), The Signs of Which Times? Chronological and Palaeoenvironmental Issues in the Rock Art of Northern Africa. Royal Academy for Overseas Sciences: Brussels. 295-326.

Hendrickx, S., J. C. Darnell, & and M. C. Gatto. 2012b. ‘The earliest representations of royal power in Egypt: the rock drawings of Nag el-Hamdulab (Aswan)’, Antiquity 86, 1068-1083.

Petrie, M. F. 1901. Diospolis Parva: The Cemeteries of Abadiyeh and Hu. London.

Robins, G. 1997. The art of ancient Egypt. London.

Williams, B., T. J. Logan, and W. J. Murnane. 1987. ‘The Metropolitan Museum knife handle and aspects of pharaonic imagery before Narmer’, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 46, 245-285.

[/expand]