A Month in the Country

Hermione Lee reflects on the particular qualities and settings of J.L. Carr’s classic novel

“No book evokes so well as this the long vistas of that high ridge of North Yorkshire between Thirsk and Sutton Bank”

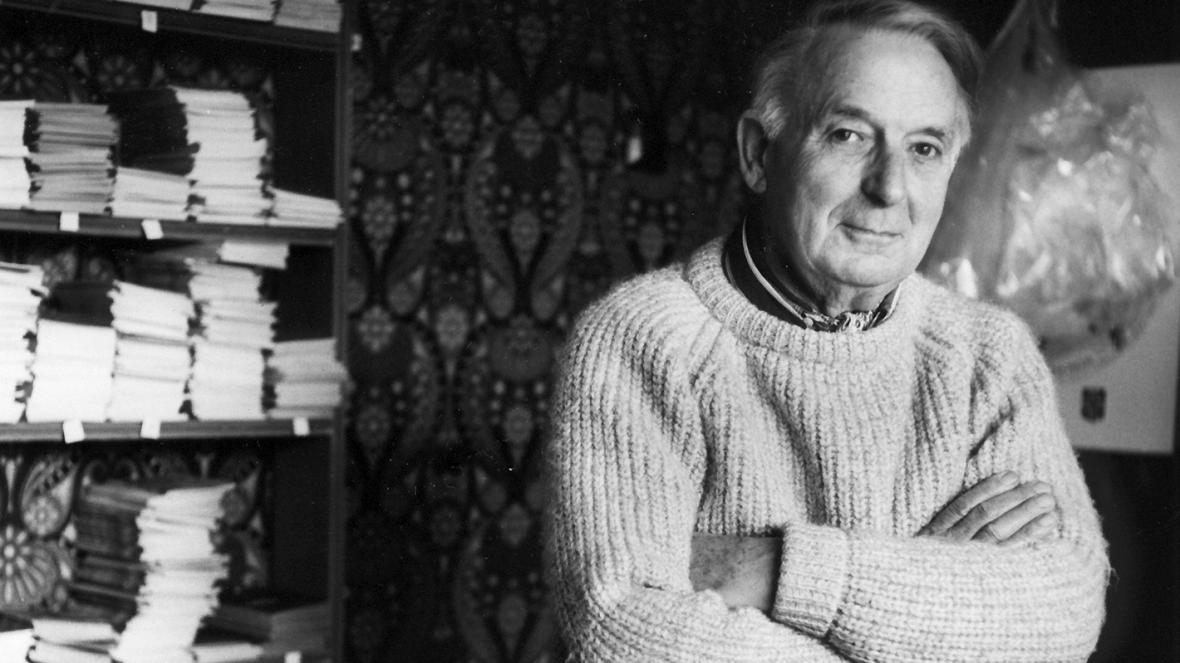

Joseph Lloyd Carr (1912-1994), better known as Jim, was a writer of laconic English humour, quiet precision, deep moral feeling, close knowledge of landscapes, buildings and history, and an interest in the heroism of obscure, unsuccessful, unprivileged people. Between 1963 and 1992 he wrote eight short novels. He was also a teacher and headmaster, a writer for children, an antiquarian, and an idiosyncratic publisher of pocket books, under the sign of the Quince Tree Press. His friend and admirer Penelope Fitzgerald said of him: “Carr is by no means a lavish writer, but he has the magic touch to re-enter the imagined past”.

His masterpiece, A Month in the Country, won the Guardian Fiction Prize in 1980, was short-listed for the Booker and was made into a film. Carr, an obstinate man, didn’t care that it was already Turgenev’s title – besides, the novella has a Turgenevian mood to it. It’s a story full of sadness and nostalgia, told by a shell-shocked war-veteran, Tom Birkin. In the “marvellous summer” of 1920, he has come, a wrecked survivor, with no money and a failed marriage, to a remote Yorkshire village, in order to uncover a huge medieval Day of Judgement painting on the wall of the village church, the work of an unknown medieval artist who increasingly infiltrates his mind. Down below, another war-veteran with a secret history, Mr Moon, is excavating a 14th century grave outside the church. They are “two of a kind”, both quietly dedicated to their specialised work, and both beneficiaries of the late old lady of the decaying manor-house, whose shrewd eye still seems to be overlooking their work. An obstructive, stiff-necked vicar, his fragile, beautiful wife, and the friendly, level-headed Yorkshire villagers (source of Carr’s typical humane, low-key comedy), become Birkin’s whole world that summer.

It is a war-novel set in peace-time, full of the horror and unspeakable fear of war-memories, which can’t be spoken about. It’s a love story of great poignancy about a missed chance, and it’s a memory of an irrecoverable past, of “blue remembered hills” that can’t be found again. “If I’d stayed there”, the sad narrator asks himself, “would I always have been happy? No, I suppose not. People move away, grow older, die, and the bright belief that there will be another marvellous thing around each corner fades. It is now or never, we must snatch at happiness as it flies”.

Above all, the novel is filled to the brim with a particular English place and time. Carr said he drew the village and its setting from his childhood in the North Riding, the church from Northamptonshire (where he spent most of his adult life), the churchyard from Norfolk and the vicarage from London: “All’s grist that comes to the mill”. Oxgodby, the name of the village, certainly echoes “Osgodby”, a village near where he went to school. And the novel brings us a vanished English country life in deep sunshine – haymaking, sleeping outdoors, Sunday School, rabbit pies, scythes, “ditches and roadside deep in grass, poppies, cuckoo pint, trees heavy with leaf, orchards bulging over hedge briars”. No book evokes so well as this the long vistas of that high ridge of North Yorkshire between Thirsk and Sutton Bank. “Day after day, mist rose from the meadow as the sky lightened and hedges, barns and woods took shape until, at last, the long curving back of the hills lifted away from the Plain. It was a sort of stage-magic – “Now you don’t see; indeed, there is nothing to see. Now look!” Day after day it was like that….” “As it lightened, a vast and magnificent landscape unfolded. I turned away; it was immensely satisfying.”

Hermione Lee was president of Wolfson College, Oxford from 2008 to 2017 and founding director of the Oxford Centre for Life Writing. Her books include Edith Wharton (2006), Penelope Fitzgerald (2013), and Tom Stoppard (2020).