The Allure of Lodore: Painting Sensation as well as Scenery

by William C. Snyder

Created at Lodore Falls in the Lake District in 1777, Thomas Hearne’s Sir George Beaumont and Joseph Farington Sketching a Waterfall (Figure 1) is a work that resists the usual categorizations of late eighteenth-century landscape painting. A scene in pen-and-wash, it allows us to glimpse an early model of English visual artists embracing elements of native landscape on its own terms.

In executing this image, Hearne discounted a Claudean approach, eschewing imaginary persons occupying wistful atmospheres, or pastoral figures roaming beneath relics of architecture. And, while the painting contains some picturesque elements––a rugged scene mixing beautiful and sublime–– Hearne avoided placing a frame around the view, disqualifying it as a “prospect” favoured by contemporaries William Gilpin and Uvedale Price.

Instead, Hearne requires of us a fluency of gazing: to perceive a location where nature is active instead of static, to discern his own friends in the exercise of capturing a wilderness within which they are actors, and to behold an experiment in conveying atmosphere. Yet even as it edges toward such “romantic” qualities, the painting does not aspire to the naturalism, chromatic intensity or imaginative power found in the next generation of British painters, a number of whom paid homage to Lodore Falls in later decades (including Constable, Turner, Ibbetson, Towne, de Loutherberg, Sunderland and Girtin).

Lodore Falls first gained notoriety in the mid-eighteenth century, via descriptions offered by writers Thomas Gray, John Dalton and John Brown, whose verbal accounts from the 1750s and 1760s were poetic and pictorial. In his 1769 touring journal Gray depicted “Lodoor” Falls as a stream “nobly broken, leaping from rock to rock, & foaming with fury” . . . from a height “about 200 feet” with a “towering crag, that spired up to equal, if not overtop, the neighbouring cliffs” with the surrounding area consisting of a “rounder broader projecting hill shag’d with wood & illumined by the sun, wch glanced sideways on the upper part of the cataract”. These impressions were included in a collection of Gray’s works, edited by William Mason, in 1775.

Joseph Farington (1747-1821), an understudy to Richard Wilson (1714-1782), appears to have been struck by Gray’s exalting rhetoric. According to John Murray, Farington traveled to Keswick in 1775 proposing to illustrate Gray’s views, but that plan was not realized. Nevertheless, Farington was able to trek through parts of the Lakes during that autumn and the following summer, explorations which provided familiarity with topographical features, allowing him to guide Hearne and Beaumont the next year.

Farington, Hearne and Beaumont all shared some interest in non-idealized landscapes. Each had previously traveled to the west and north of England and to Scotland––where terrain was wilder, more dramatic or more surprising than the gracious plains and hills of Oxfordshire, Staffordshire, or Worcestershire. At Derwentwater they came to realize that familiar or academic approaches to image-making needed expansion; sublime panoramas and the capricious weather and modulating atmospheres of the mountainous lakes urged all three artists to enlarge their vision. For a few weeks in August of 1777 the men traveled to the North Lakes to indulge their desire to paint pure landscapes together, on location, drawing upon each other’s technical and academic skills as well as upon one another’s perspectives and approaches.

The plan to work around Derwentwater probably arose from Farington’s standing desire to pictorialize Gray’s tour. Taking into account dates given on his sketches, we might infer that Farington took three tours in 1777: working in and around Grasmere and Keswick in June, heading to Carlisle to paint Corby Castle in July, and tracing through the northern Lakes from mid-August to mid-September. (Sketches and drawings indicate that this third outing took him from Cockermouth on 14 August and back to Keswick by 10 September. Dates affixed to pencil sketches of High Crag and Gatesgarth suggest that after the stay at Lodore his itinerary followed Honister Pass, ending at Cockermouth, where he produced a sketch of the northwest view of the castle).

The Low Door Hotel, situated at the entrance to the Borrowdale Valley, served as a pied-à-terre for the three artists. This location provided vistas that could be enjoyed from Derwentwater’s southern shoreline. The marsh in front of the hotel supplies choice views of Skiddaw, six miles to the north, looming above Keswick with the breast of the Lake in the foreground. A nearby pier makes access to other points on the Lake possible, and images from these locations were produced by these painters as well as by many others in later years. Today, lower Lodore Falls is actually within hotel property, an un-demanding ten-minute climb on foot, about twenty minutes with equipment.

On 27 August the three painters, along with a footman and a dog, bundled materials of composition and climbed a path alongside the cascade of boulders to their right. A Farington pencil sketch includes the script “Lodore Cottage from the Waterfall” in the lower left corner. On the back is “27 8 1777”. This artifact is likely Farington’s view in the Hearne canvas. (See Figure 2.)

‘An extraordinary idea somehow transpired: Beaumont and Farington resolved to paint from within the waterfall.’

Figure 2. Joseph Farington, Lodore Cottage from the waterfall, 27 8 1777. Enhanced digital image, The Wordsworth Trust.

Before the rocky channel got too steep, they unpacked and began to set up. An extraordinary idea somehow transpired: Beaumont and Farington resolved to paint from within the waterfall. They secured two easels on top of large boulders. Hearne, the antiquarian and architectural draughtsman so familiar with composing from a distance, found a spot about eighty feet away, under a small clearing beneath a coppice of trees. On the same plane as his mates, with the falls tumbling aside a 35-foot limestone wall, he positioned to record his colleagues situated against the impressive backdrop, as they went about the unusual action of sketching in ink, outdoors, from an atypical point of view, surrounded by movement and moisture.

Hearne had been comfortable working outdoors from his years of rendering buildings. But the scene at Lodore Falls presented a pure landscape, and was less subject to conceptual control than a house or ruined abbey. So the painter nodded to a few familiar techniques of the continental picturesque tradition. The appearance of figures below an imposing rock façade with rugged features is a consistent idiom in the work of Salvator Rosa, Italian master of sublime landscapes and an influence on English nature painters in the latter part of the eighteenth century. Also, terrestrial elements—the canopy of trees at the top, and the array of boulders below—hint at a frame for the scene, a pattern from Italian and Dutch landscapes introduced by Wilson to English places.

Yet Hearne’s effort, as well as the initiative of Beaumont and Farington, crosses boundaries into entirely new territory. First, the figures are not only real, but known by the artist. Hearne is, for the era, surprisingly personal as he breaks from his training as an objective historian and provides a kind of visual diary entry. And, while picturesque or antiquarian painting typically includes animals, peasants, or children, they tend to be anonymous reference points who serve to convey a sense of proportion. Here Hearne names the performers, divulges clues about sensibility and motive, and implies his own participation by capturing the same subject as his colleagues. He punctures the standard screen of seeing the world, of presenting the view as “out there”.

With a rigid neo-classical frame elided, and with no long view or vista, Sir George Beaumont and Joseph Farington Sketching a Waterfall conveys a sense of enclosure, if not intimacy––between man and nature, and among the painters. Without a horizon, the margin between subject and observer is reduced, as Hearne refuses to artificially position trees or rocks to frame the figures. Beaumont and Farington are affiliated with the scene that they are involved in capturing—artists as subjects––woven into the larger visual web. Enveloped in the waterfall, their figures do not command immediate attention; we are prompted by the title to seek for them—and then to enter into the image, to assemble it ourselves.Hearne captures a moment in time integrating real subjects, natural elements, and local atmosphere, thus separating from historical or mythological landscapes which transport us to a different era, far removed from current life and conditions. Here we are in the present day viewing men at work at a specific time in a known place.

The paraphernalia of the artists––the brushes, umbrellas and tripods–– insinuate shapes found elsewhere in the painting: the sloping tops of boulders, or the trunks and branches of some of the trees. Also, seeming to borrow from Rosa, Hearne takes license to accentuate the rock wall, bending it toward the artists for dramatic effect, as the axis of the actual slab is more vertical in proximity to the stream. (See Figure 3.)

The placement of the two artists––not just in proximity to the water, but inside the rock channel of the falls—is striking for the time. The germ of the idea to attempt composing from such a position may never be known, but Beaumont and Farington might have been seeking immediacy, to paint sensation as well as scenery. In any case, they were undertaking quite a challenge. At Lodore Falls, the set-up of equipment required of oil painting (involving larger canvases than pads or sketchbooks) would have been physically difficult. The unevenness of the boulders and the variation of their size, in addition to the wetted surfaces and slippery moss, required extensive preparation before any brush touched canvas.

To navigate this problem, the men likely customized their supports, scanning the ravine’s bed for small sandy pods flat enough to allow sturdy footholds. Still, the painting presents the canvases as a bit askew; the ruggedness of the landscape is complemented by the ruggedness of the process, which invites another potential interpretation: was the sight of his fellows climbing over slick rocks to install two easels so unique that Hearne decided that such an act of human enterprise was just as worthy of portrayal as the falls? In any case, Hearne shows the challenges involved in painting landscapes on-site, revealing to us that era’s tools of the trade, from the mountings to the multiple umbrellas to the mahlsticks. (See Figure 4.)

‘…a kind of visual diary entry’

Figure 4. Thomas Hearne, Beaumont and Farington Sketching a Waterfall, detail.

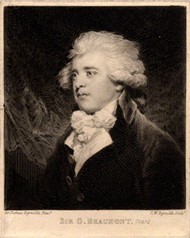

Hearne’s preliminary and larger sketch for this tableau lays out another interesting subplot in the Lodore story. A pencil drawing (17.8 x 19 cm) (Figure 5) archived in the Wordsworth Trust adds nuance to the finished work. Most notably, the preliminary sketch includes facial expressions of two of the men, gazes of satisfaction or pleasure. The closest figure, likely Sir George Beaumont (Figures 6 and 7), appears to be looking at the canvas with serene approval while he holds a brush; the standing figure, probably Beaumont’s attendant, with hands in pocket, casually admires the waterfall. The expression of the middle figure is not apparent, but the curve of the chin suggests Farington, who had a full, round face. The pencil rendition includes a dog, who is looking at Hearne, providing a point of entry into the scene for the viewer, and disrupting any sense of picturesque distance. All four figures are interconnected, yet all are looking in different directions.

The final work switches the positions of Beaumont and Farington, and obscures their expressions. The attendant is shown as sitting and is darkened, nearly lost in the composition. The dog has been erased. Different too are the posts for the easels (less rugged in the painting) and Farington’s easel has two intersecting spires with no apparent footing.

As Hearne worked the tableau into the final, larger canvas, he traded the intimate detail of the figures for the impact of boulders, slab, and waterfall. The sketch is realistic; the painting is artistic. The sketch betrays the pleasure and contentment of connections—to nature and to art, even of a brotherhood of picture-making. The painting zooms out to a view that allows natural elements—and some sense of sublimity—to prevail.

Nevertheless, the two versions of the men at their canvases allow two perspectives of an experiment in process. The three artists were outside their usual spheres, and certainly beyond the compass of their masters. Castles, priories, goddesses, shepherds, estates, engravers and a picturesque frame were not in play. Instead, the focus is on flesh-and-blood British gentlemen enjoying an actual British place in a specific moment of time. John Constable, who eventually became good friends with Sir George, might have titled this work “Waterfall: Noon.”

Finally, while Hearne’s execution is remarkable enough, his point of view is rare for the time. Standing on a small plateau, a twenty-first century visitor to the Falls can approximate Hearne’s position and gaze upon the disheveled boulders that upheld Beaumont, Farington and their easels, imagine the two painters putting pencil to palette after studying the cascade, and perhaps occasionally glancing back at Hearne, thinking that the Falls were his subject, little realizing that they were subjects themselves, part of the scene, being immortalized.

Somewhere during their long friendship, Hearne made a gift of his Lodore watercolour to Sir George, and, except for occasional exhibition, the canvas evidently was in the Beaumont estate until obtained by the Wordsworth Trust in 1984.

If it is accurate to say that the “Lakers” of the Romantic age found qualities in Cumberland and Westmoreland that were already inside themselves, we should see Farington, Hearne and Beaumont as belonging to an earlier sensibility, teasing out a new kind of art in an elemental way––where classical vision and technical training were tentatively fused with a varied and spectacular topography. In the Lakes, and especially at Derwentwater, the three men began to extend the boundaries of their academic preparation so that they could do justice to Cumbria’s unique terrain, atmosphere, and history. The vicissitudes of the Lakes provoked their imaginations, summoning them to dabble with effects, perspectives, techniques and moods which presaged their later works, and which would become standard in the painting of the next generation.

William C Snyder is an independent Romantics scholar based in Pennsylvania